- History

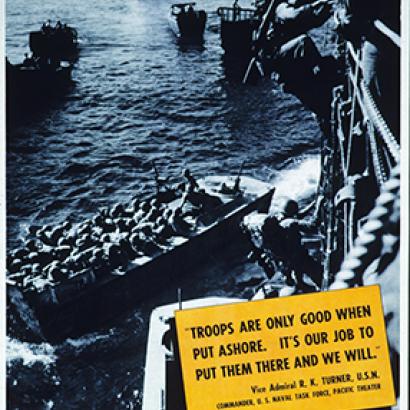

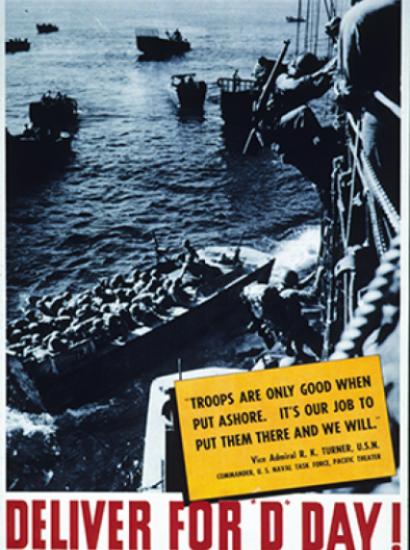

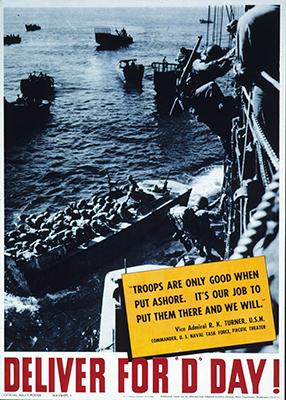

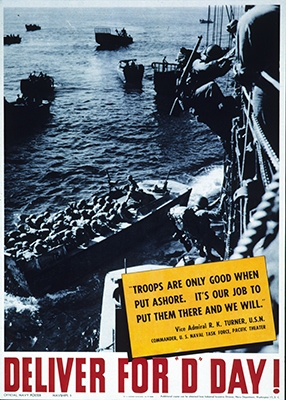

Seventy-five years ago, American, British, Canadian, and French soldiers stormed ashore on the beaches of Normandy to begin the final campaign in the liberation of Europe from Nazi tyranny. It was an operation four years in the making, ever since the withdrawal of British and French troops from Dunkirk after the disastrous battle for France left the Wehrmacht in control of Northwest Europe. The campaigns waged by the Grand Alliance—the Battle of the Atlantic, the strategic bombing offensive, the invasions of North Africa and Italy— were preludes to this decisive moment in World War II. Millions of soldiers and tens of thousands of pieces of military equipment were staged in Britain in anticipation of this venture.

Despite overwhelming Allied superiority in manpower and equipment, the invasion’s outcome was not predetermined. The weather did not cooperate; cloud cover created navigation issues for aircraft and resulted in badly scattered airborne drops and inaccurate bombing missions, heavy seas resulted in the swamping of much of the armor that attempted to swim ashore using flimsy amphibious kits, and seasickness sapped the energy of the soldiers ferried to beaches in Higgins boats and other landing craft. At Point du Hoc, American Rangers improbably scaled nearly vertical rocky cliffs to knock out a critical German gun battery that could have dominated the landing beaches. As President Ronald Reagan recalled at the 40th anniversary of the invasion, “the Rangers pulled themselves over the top, and in seizing the firm land at the top of these cliffs, they began to seize back the continent of Europe.” On Omaha Beach, German defenders killed or wounded upwards of 2,000 American soldiers, leaving the outcome of the invasion in doubt until infantrymen slogged their way up the bluffs and overcame the Atlantic Wall by the end of what came to be known, in the words of historian Cornelius Ryan, the Longest Day.

The triumph of Allied forces on this fateful day was the first step in what Allied commander General Dwight Eisenhower termed “the Great Crusade.” The tide had indeed turned, with “the free men of the world…marching together to victory.” Had the day turned out differently, the impact on the future course of world history would have been significant. Another invasion that year was problematic, but the Red Army juggernaut would have continued its relentless march westward towards Berlin. Allied bomber armadas would have continued their inexorable campaign of destruction in the skies over Germany. World War II in Europe might very well have ended with the Red Army positioned along the Rhine River or in Paris (Tsar Alexander I’s troops had gotten there in 1814, after all), or Berlin may have disappeared under the canopy of an atomic mushroom cloud. The future of Europe—the creation of NATO and the European Union under an American security umbrella—may have instead belonged to the Russian bear.

Instead, D-Day and the battles that followed made possible an era of American supremacy in world affairs, a fitting legacy for the “Greatest Generation” that landed on the beaches of Normandy three quarters of a century ago today.