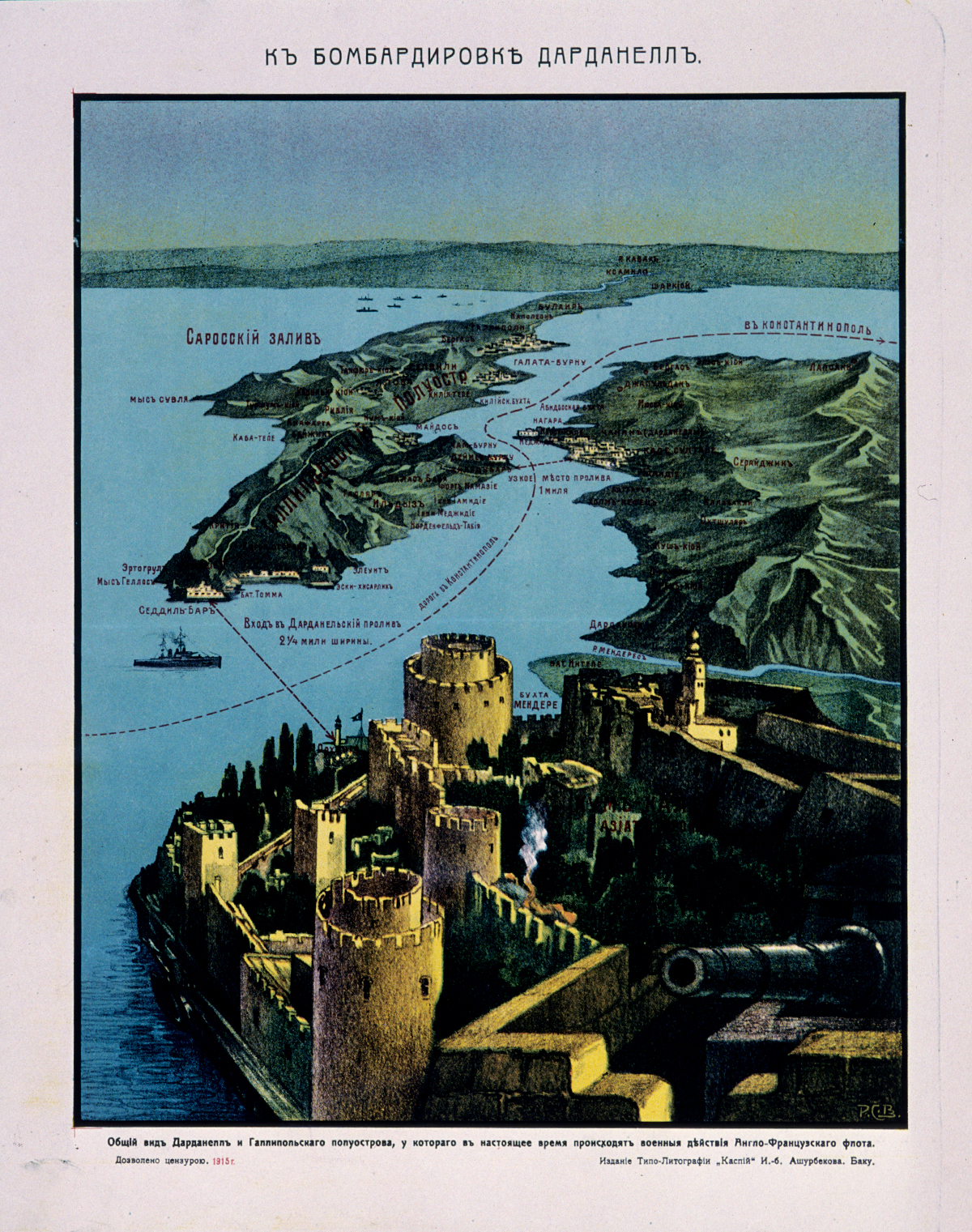

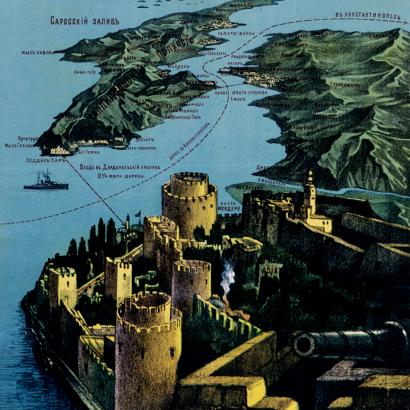

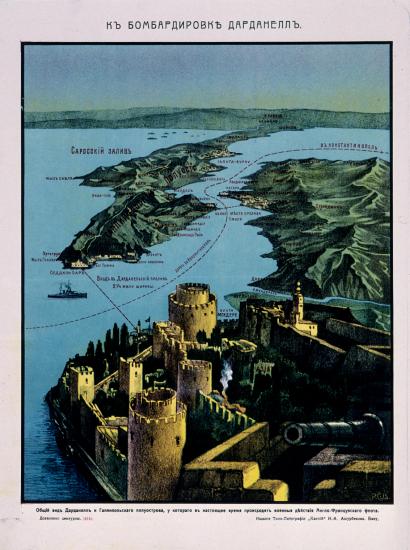

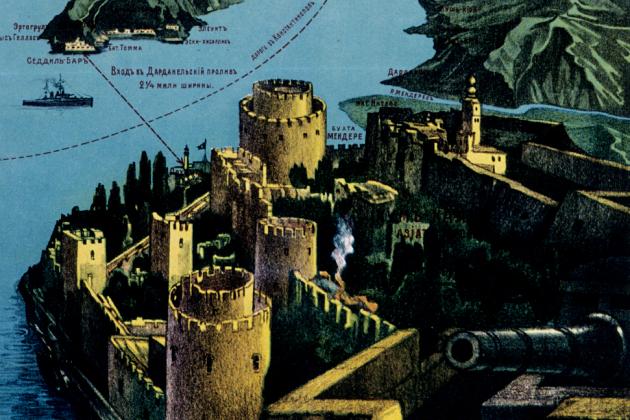

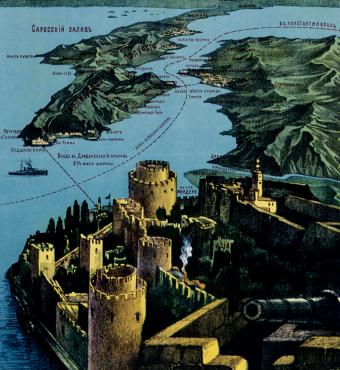

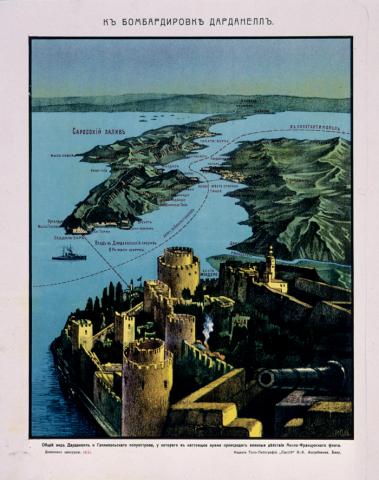

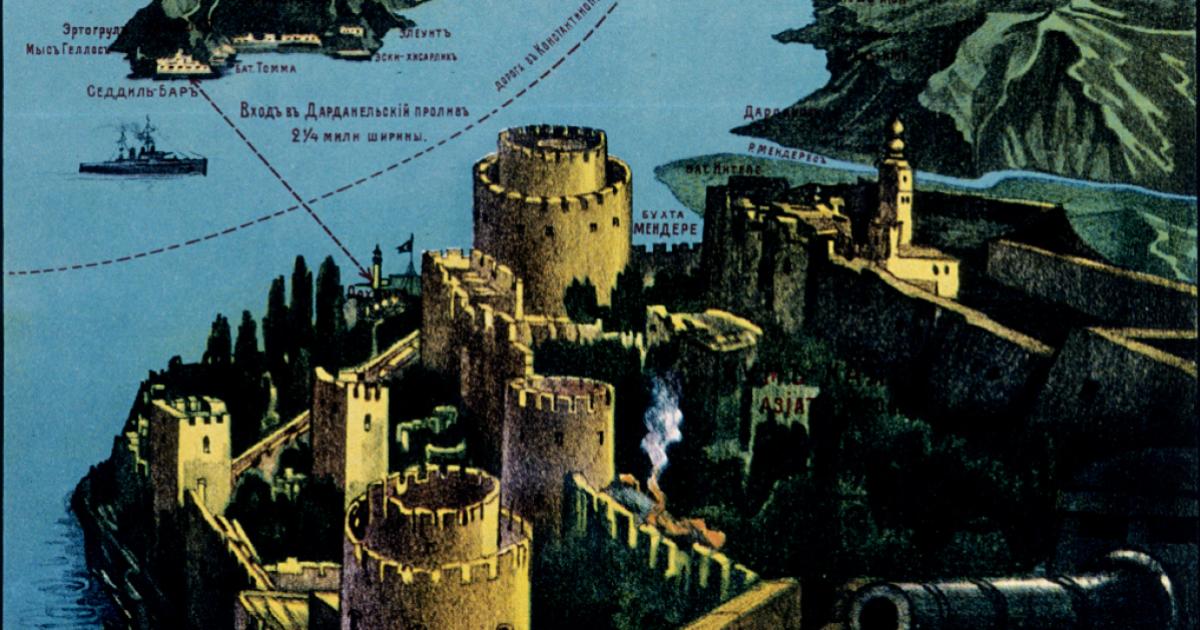

More often than not the past provides the present with serious warnings about the dangers of the world in which it lives. Nothing better exemplifies this truism than the geographic realities inflicted by the Deity on the territories stretching across south-eastern Europe from the Danube in the west to the great mountains covering the Caspian Sea in the east. To the south, the largely waterless Anatolian plateau blocked much of the Black Sea from access to the Mediterranean with the exception the Dardanelles, a narrow strait that had made it one of the most important strategic points of the fifth century B.C., just as it has proven to be in the twenty-first century.

The gods had also provided the first settlers of Ukraine with unbelievable riches of raw materials. From its center to far in the east, deep, dark soil has provided a massive agricultural bounty, unmatched elsewhere. Small wedges of farms allowed for the production of wheat and sunflower seeds. Ukraine’s agricultural bounties provided enormous wealth which soon drew large numbers of Greek merchants across the Black Sea in search of agricultural sustenance which was so rare in the Aegean.

A careful reading of Thucydides indicates that much of the Peloponnesian war took place in a great contest for control of the entrance to the Dardanelles. Spartan efforts to undermine the Athenian Empire began and ended; they failed dismally because Spartans proved to be dreadful sailors. The most effective response was the one launched by the greatest of all Spartan generals, Brasidas. Beginning in 424 B.C., the Spartan general recruited an army to launch an invasion along the western and then the northern coast of the Aegean with the eventual aim of capturing Byzantium and control of the Dardanelles. Once they were in Spartan hands, the Athenians would find themselves denied access to the food supplies of Ukraine so essential to their survival.

As his campaign force gathered at Megara, Brasidas was able to thwart an Athenian coup attempt, which would have cut the Peloponnesus off from the rest of Greece, and probably brought the Athenians victory in the war. Continuing north along the western coast of the Aegean, Brasidas destroyed much of the Athenian position and brought crucial cities over to the Spartan side. His greatest victory came at Amphipolis in 422 B.C., where his army defeated Cleon’s army, but he died in battle at the front of his troops. His demise ended the possibility that the Spartan offensive in the north would have undermined Athens’ position in northern Greece entirely.

Much of the remainder of the war revolved around the disastrous Athenian expedition to seize the city of Syracuse in Sicily. After that defeat, the focus of the war returned to the Dardanelles. Despite their desperate situation, the Athenians hung on. Not only did they maintain their democratic form of power, but they regained most of their control over much of their empire. What they could not control was their own political self-control. At the battle of Aegospotami, the Athenian fleet finally went down to defeat at the hands of the Spartans and their allies in 405 B.C.

Of course, the Dardanelles never lost its strategic, military, and diplomatic importance. Seven-hundred years after the end of the Peloponnesian War, the Roman emperor Constantine would found his new city of Rome (Constantinople) on the remains of the city of Byzantium where, protected by the Dardanelles, it would be the defender of Western Civilization for the next 1,000 years.