- Politics, Institutions, and Public Opinion

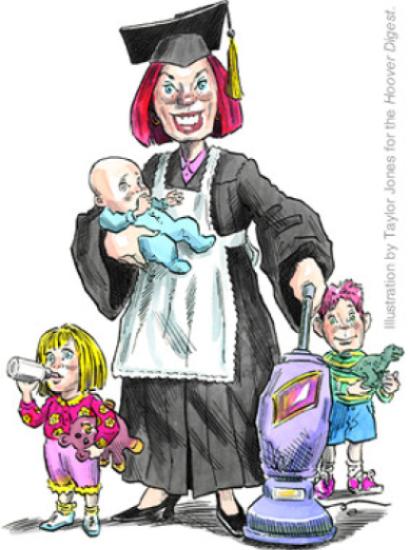

Judging by letters to the editor and furious Internet circulation, the New York Times struck a collective nerve with its front-page story several months ago announcing that “Many Women at Elite Colleges Set Career Path to Motherhood.” According to the article, surveys of 138 female students at Yale revealed that roughly 60 percent planned to cut back or stop work when they had children. Scattered interviews at other high-end schools confirmed that many of today’s young women do not dream of supercharged 12-hour days at the future office, at least not when their children are young. And though hardly scientific, the Times report did track with similar recent soundings on other campuses, as well as with the statistical fact that well-educated women with youngsters in the house are indeed now slightly more likely to be at home than were women in the same group a decade earlier.

What accounts for this gradual but real shift in what many of today’s privileged young women seem to want? Interestingly enough, one factor appears to be personal experience. “I’ve seen the difference between kids who did have their mother stay at home and kids who didn’t, and it’s kind of like an obvious difference when you look at it,” one explains. “I see a lot of women in their 30s who have full-time nannies, and I just question if their kids are getting the best,” says another. To the exasperation of the older generation of feminists now shepherding them through elite institutions, at least some of these young women have grown up in the very world their progressive foremothers dreamed of—and reject it precisely because they know it.

Just as interesting, this demurral based on experience is part of a much larger story now being written by today’s adolescents and young adults. A funny thing happened to the kids raised on Sesame Street and all the other fare touting politically correct notions of the family: They grew up—and as they did, a significant number looked at their own lives and found progressive happy-talk about the family coming up short.

This questioning—an unforeseen domestic blowback—may not have the status of a full rebellion. But certainly there is insurgency on several fronts. Women must have full-time careers to be fulfilled (the dogma that is questioned in the Times story and elsewhere) is one such proposition now openly contested. Now consider two other articles of progressive faith that are similarly under assault by young voices of experience: that all families are equal from the child’s point of view, and that divorce and other forms of family breakup or novelty do no lasting harm.

For years now, scholarship based on actual testimony of kids from broken homes—in particular, Judith Wallerstein’s unequaled 25-year study, The Unexpected Legacy of Divorce—has successfully challenged and overruled both ideas. Hundreds more dissenting voices of young adults, surveyed in Elizabeth Marquardt’s new book, Between Two Worlds, confirm the findings of Wallerstein and like-minded revisionist scholars. Of course the usual qualifiers apply—not all biological parents can live together, not everyone suffers equally from a broken home, and many children appear to weather losing one or another parent just fine. But the work of Wallerstein and Marquardt, grounded firmly on what the grown-up children of divorce report themselves, confirms what some enlightened people still want very much to deny: The children of broken homes operate at an emotional disadvantage to their peers with intact biological parents—a disadvantage that persists, in the telling of many, on into adulthood.

One does not need to look to scholarship alone to find many of today’s kids and young adults openly nostalgic for that mother of all scapegoats, the nuclear family itself. The most dramatic evidence of this yearning comes from an unexpected place: popular music.

To survey the biggest acts of the last several years—among them Blink 182, Papa Roach, Korn, Nickelback, Everclear, Pink, Good Charlotte, Tupac Shakur, and Eminem—is to find oneself far off the progressive reservation indeed. Unbeknownst to many adults, divorce, abandonment, dysfunction, and absent parents are now some of the themes that make contemporary platinum go round. Aforementioned artist Pink, to cite one of many examples, devoted an entire (hit) album to the subject of her parents’ divorce. Good Charlotte, profiled on the cover of Rolling Stone as “The Polite Punks,” sing repeatedly of family breakup (three of the four members had divorced parents, and two went so far as to legally change over to their mother’s maiden name). Everclear’s ubiquitous top-40 hit of a few years ago, “Wonderful,” was one long lament for a broken home by a boy narrator who wanted his family back—and was only one of many contemporary hits that could be summarized in exactly those words.

Similarly, parents who have long wondered what makes Eminem the best-selling recording artist in America might look no further than these themes, scrawled large on every album he has released: My father left me; my mother neglected me; I’ll never abandon my own child the way my parents did me. Of course Eminem’s music, like that of most other current balladeers, also plumbs themes of sex, drugs, and rock and roll (to say nothing of date rape, mayhem, and violence). Yet its insistence on the damage done by abdicating adults is also an unmistakable, if backhanded, compliment to the nuclear family. And it affirms, along with many other such voices, that from the point of view of a significant number of young adults, at least some of the social experimentation of the recent past has gone awry.

As progressive sociologists like to point out, widespread divorce, illegitimacy, dual-income homes, and other changes to the way kids now grow up are indeed here to stay. As they also like to point out, children are in fact resilient, and many will simply thrive no matter what is thrown their way. But what emanates from the popular culture these days is a dissenting point: Some will not. Moreover, in an era when half of all children will live without a biological parent in the home at some point in growing up, when the 2004 statistic for babies born to unwed mothers reached a record 34-plus percent, and when creative minds demand ever more recognition for what are said to be ever braver new experiments in family formation, the unhappy testimonials of these former children have not peaked. They have only just begun.