- History

- Revitalizing History

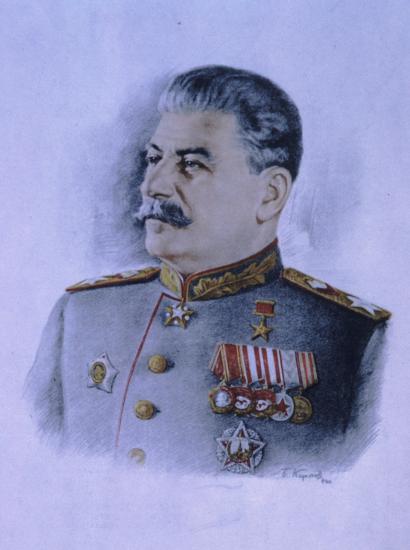

From 1936 to 1938, Josef Stalin unleashed a vast purge targeting political opponents, real or suspected, as well as anyone who could potentially become an opponent. The Great Terror saw the arrests, torture, imprisonment, or execution of over a million Soviet citizens, as well as thousands of foreign communists who had expected to find a refuge in Moscow and a protector in Stalin. The butchery and torment struck all but one Politburo member, thousands of government officials, scientists, artists, and, ultimately, the secret policemen themselves, until those who knew where the bodies were buried were tossed in mass graves themselves.

The purges left Stalin the unquestioned—indeed, unquestionable—master of the Soviet iteration of the Russian Empire. Then, less than three years after the last show trial, that domestic slaughter almost cost him everything: He had failed catastrophically in his appreciation of external threats—above all, by underestimating and even trusting Adolph Hitler.

Stalin’s great practical error had been his drastic purge of senior military men. While the exact figures will never be known, up to eighty percent of Soviet marshals, generals, admirals, and colonels were either executed outright or imprisoned in the far reaches of the Gulag. The most talented flag officers died or disappeared, leaving a handful of mediocrities and inexperienced junior officers in charge of a vast, demoralized military. Survivors were not inclined to complain about the military’s shortfalls.

The result? When the Nazi Blitzkrieg thrust into Russia, Stalin’s purified military lost over two million men in two months, killed or captured. Stalin’s henchmen had to scour far-flung prison camps for senior officers who had been spared a secret-police bullet in the head.

As an aside, some rehabilitated officers later published war memoirs that revealed a wry sense of humor: one lauded commander wrote that, when war broke out, he had been “recalled from a vacation” in Russia’s hinterlands.

Throughout history, political purges of military professionals, whether in ancient Rome or China today, have rarely proven wise.

Of course, this has not been a problem in the Armed Forces of the United States. Except for our interlude of madness in the mid-nineteenth century and a single bombastic general in the mid-twentieth century, the officer’s oath to the Constitution has been honored scrupulously by those in uniform and respected by their civilian masters. Officers keep their political views to themselves while on active duty. They are rigorously subordinate to the commander-in-chief, obeying every lawful order issued.

But they are not wantonly subservient. They may play office politics, but they do not take political sides. While presidents from both parties have had their favorites in uniform, we have never suffered a president who dismissed or appointed generals and admirals based solely on personal political loyalty. Not every flag officer has been a genius, but, in my own service, I never met one who lacked basic competence (which is not to say I agreed with all high-level decisions). Mediocrities sometimes reach high rank, but, overall, our military leadership has been and remains the best in the world.

We must do all we can to keep it that way. Firing and hiring senior officers based on their imagined politics or because they provided uncongenial professional advice is a formula for disaster. In a war with China, for example, things would move hyper-quickly. Unlike Stalin, an American president would not have months to swap out incompetent commanders. We must be ready. Always.

Our blessed Anglo-American tradition has kept our military forces out of politics. It is up to us to keep politics out of our military.