- Economics

- Answering Challenges to Advanced Economies

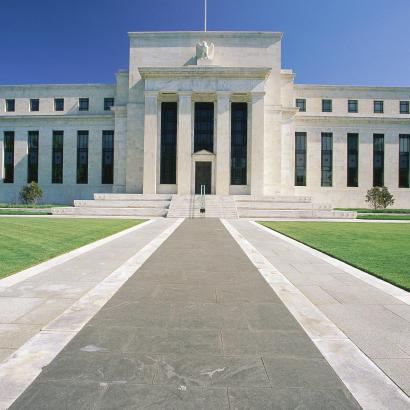

This essay is adapted from Fifty Years of the Shadow Open Market Committee, a publication of the Hoover Institution Press. Based on a two-day symposium held at the Hoover Institution, the book examines the evolution of the Federal Reserve’s monetary and credit policies and critical issues it faces today.

The Shadow Open Market Committee (SOMC), a small committee of academic and business economists, was established in the early 1970s by leading monetarist economists Allan Meltzer, Karl Brunner, and Anna Schwartz to promote the argument that inflation was a monetary phenomenon. The Great Inflation and the disarray of economic policy-making of the 1970s provided the ideal context for the committee’s establishment: inflation had ratcheted up beginning in the mid-1960s, driven by expansive government spending and monetary accommodation.

The founders of the SOMC emphasized that reducing the rate of growth of the money stock was necessary to lower inflation. Milton Friedman had initiated and championed this monetarist argument. He had battled since the 1950s with the mainstream Keynesian economists who posited that monetary policy was far less effective than fiscal policy.

Friedman and Schwartz, his principal coauthor, (and several other prominent coauthors and students) forcefully argued that “money matters,” and that changes in the quantity of money interacting with a stable money-demand function were the key drivers of nominal income, with its effects first affecting real activity and then the price level. By contrast, the Keynesian view emphasized the importance of other sources of aggregate demand, particularly fiscal policies—spending and taxes.

A key tenet of Friedman’s view was that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.”

Several things contributed to the Shadow Open Market Committee’s 1970s success. Its simple money-growth target proposals were easy to understand and could be tracked and monitored. The committee’s communications were well organized and its policy recommendations attracted attention. The committee fashioned itself as an “outside watchdog” of the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy-setting conducted by its Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). During the 1970s it successfully promoted the importance of money and influenced the debate in Congress and at the Fed about how to reduce inflation.

Along with other monetarists, the SOMC most likely influenced Federal Reserve chair Paul Volcker to shift gears in 1979 toward its successful disinflation based on reducing growth of a monetary aggregate—nonborrowed reserves—and allowing short-term interest rates to fluctuate widely.

The evolution of issues

Over time, two themes have influenced the Fed’s monetary policy and the debate about how to conduct it: the evolution of the Fed’s interpretation of its dual mandate, and the evolution of what “rules” mean in the ongoing debate about the benefits of rules versus discretion.

During the Great Moderation of the 1980s and 1990s, the SOMC continued with its strictly monetarist monetary-policy recommendations of targeting money growth without factoring in fluctuations in money demand. It became outdated and fell out of favor as the Fed and the economics profession shifted back toward the targeting of interest rates. The SOMC provided sound advice on other policies. It properly cautioned the Fed against using monetary policy to stabilize the US dollar while advocating flexible exchange rates and free international trade. And it promoted sound fiscal policy and argued in favor of rules that would constrain government spending and deficits.

Looking over the past half century, the Fed has made three major and costly monetary policy errors: the high inflation of the 1970s; its extended low interest rates of the early 2000s, which facilitated the debt-financed housing bubble that evolved into severe financial stresses; and the high inflation of the 2020s. Before and during each episode, the SOMC provided warnings and sound policy advice. The SOMC’s early warnings about the inflationary impact of unprecedented deficit spending and money growth in 2020–21 were prescient. Unfortunately, the Fed did not heed the SOMC’s warnings and recommendations on the last two events.

The SOMC has always emphasized sound money and the importance of a nominal anchor in the conduct of monetary policy rather than a discretionary approach. The committee has highlighted the benefits of a rules-based monetary policy. It also has highlighted the benefits of central bank transparency. On fiscal policy matters, the SOMC has urged fiscal restraint and the importance of the Fed’s steering clear of fiscal policy and its involvement through its asset purchases and balance sheet. These stances align closely with the beliefs and research of Hoover Institution scholars.

In the half century since the tumultuous 1970s, monetary policy issues have evolved, and the SOMC has continued to conduct research and provide policy advice on central bank policy-making. The range of the SOMC’s expertise has broadened as the Fed and global central banks have expanded their roles and the scope of monetary policy. Adding to the committee’s legacy of monetary policy scholarship, SOMC members include noted experts in banking and bank regulation, financial stability, the Fed’s expanded balance sheet, and its role in international finance, monetary history, and governance issues. Over time, several members of the SOMC have joined the Fed, and the current SOMC includes several former Fed members.

The SOMC research policy recommendations have broadened from its strict monetarist foundations, formed by the following core beliefs:

- Sound monetary policy, guided by systematic rules whose primary objective is stable and low inflation, as the best foundation for healthy economic performance;

- Transparency and accountability;

- Systematic and economically rational approaches to financial regulations.

A healthy, constructive Fed critic

The current environment sets the stage for the importance of the Fed’s getting things right. The 2020s high inflation dispelled the notion that the inflation of the 1970s was history that would not be repeated. Although inflation has receded toward the Fed’s 2 percent target, the dramatic rise in the general price level, and the Fed’s recent missteps, affect current economic behavior and resonate with the public.

The Fed’s understatement of the unprecedented surge in money supply that the earlier SOMC had warned about, and its reliance on discretion rather than rules like the Taylor rule—both of which have been a focus of current SOMC research—provide the perfect backdrop for the history of the SOMC and the evolution of monetary policy. (Hoover fellow John B. Taylor’s famous rule, which is an essential chapter in every central banker’s guidebook, and his pioneering research on monetary policy rules have been at the heart of the SOMC’s core beliefs for the past three decades.)

The modern SOMC continues to argue for rules-based policies and recommends that the Fed pursue a narrower scope of policies, including staying clear of credit provision, and focus on policies within its ability to achieve.

The Shadow Open Market Committee continues to thrive and to contribute important research and insights.

The current issues facing monetary policymakers are critically important to healthy economic performance, as were those of the past. In an era in which the Fed is most comfortable listening to friendly voices, the SOMC’s role as an outside watchdog remains critical for the future.