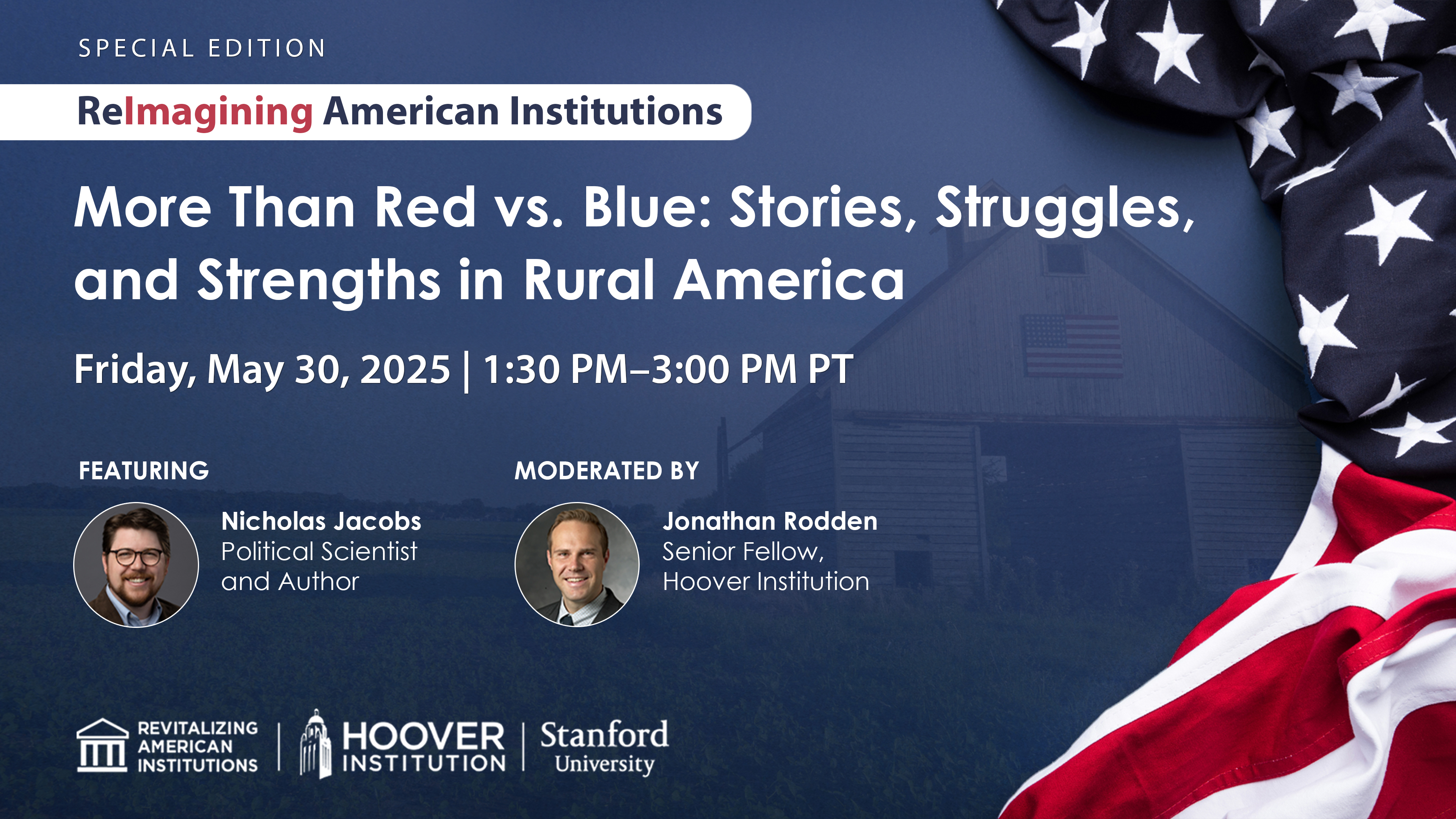

The Center for Revitalizing American Institutions (RAI) hosts More Than Red vs. Blue: Stories, Struggles, and Strengths in Rural America on May 30, 2025, from 1:30-3:00 p.m. PT.

Rural America is often reduced to a political talking point — red states, blue states, culture wars. But there’s a deeper story, rooted in place, community, and history. Drawing on his own research, Nicholas Jacobs, co-author of The Rural Voter: The Politics of Place and the Disuniting of America, explores what it means to understand rural life on its own terms — and why doing so matters now more than ever.

This event is hosted by the Center for Revitalizing American Institutions (RAI) as part of the People, Politics, and Places Fellowship, an initiative that seeks to authentically engage Stanford students with the experiences, challenges, and contributions of rural communities, while reaffirming higher education’s responsibility to serve all corners of the nation. Following a presentation of his research on the political and cultural dynamics shaping rural America, Professor Jacobs will be joined in conversation by Professor of Political Science and Hoover Institution Senior Fellow Jonathan Rodden.

>> Speaker 1: Good afternoon, my name is Tom Schnabel. I serve as the Assistant Director of the center for Revitalizing American Institutions here at the Hoover Institution. Thank you for joining us today. Before I begin, I'd like to do a little bit of housekeeping. First I wanna recognize our partners.

We had a good bit of help planning the event today. We had some help from the Bill Lane Center for the American west, the Haas center for Public Service, and the Stanford Rural Engagement Network, otherwise known as the Rural Club. And Jesse, the incoming president is here today.

Jesse, raise your hand. There you go. We also had some promotional partners. The center for Democracy Development and the Rule of Law, the Stanford Political Union, the Stanford Democracy Hub, Stanford and government, and the McCoy Family center for Ethics in Society. And last but not least, we're very grateful for some financial support to support.

Nicholas's visit with us comes from the Academic Residential co Curriculum Fund administered by the Vice Provost for Undergraduate Education. I also wanna let everyone know that today's event is being recorded as a special episode of our Reimagining American Institutions webinar series and will be available@hoover.org rai in the next few days.

So today's session will consist of an opening presentation followed by a conversation between our guest and a moderator, and we'll conclude with questions from you all to our panelists. Before we begin, I'd like to take just a minute to tell you a little bit about who we are and why we're hosting a conversation about the stories, struggles and strengths in rural America.

RAI, which is the center for Revitalizing American Institutions, is Hoover Institution's first ever center, and it's a testament to one of our founding principles, Ideas Advancing Freedom. The center was established to study the reasons behind the crisis in trust facing American institutions, analyze how they're operating in practice and and consider policy recommendations that could help rebuild trust and improve effectiveness.

Our work focuses on government institutions at all levels and all branches, civil society institutions and democratic citizenship. That's essentially the way that individuals form relationships and understand institutions. So to get at why we're having this conversation, I wanna just ask how many of you in this room grew up in or currently live in a rural place by show of hands?

Okay, so that's a good number of you. I'm now tempted to say, how many of you know what the H's stand for in 4H because we have such a good. Okay, we got at least one. I should have brought a door prize, so if this room were filled with a representative sample of 100 Stanford students, or for that matter, 100 of Stanford's alumni who live in the United States.

About five hands would have gone up. Comparatively, 19 or 20 hands would be lifted in this room if it were filled with a representative sample of US Citizens. So Nick and I have, Nicholas and I had dinner with the Stanford Rural Club last night and we talked about the lack of internship opportunities in rural locations and that almost all of the students who do go on internships in rural places are actually students from rural places.

That isn't only a problem for Stanford, that's actually a problem for Colby College. It's a problem for a lot of our peer institutions. It's also the reason that we're piloting a new fellowship called the People, Politics and Places Fellowship, where we've recruited students who have had limited exposure to domestic rural communities and ask them intentionally to seek to develop a deeper understanding and knowledge of domestic rural life.

And they're gonna be doing that this summer by spending time in places like Alaska and in Viroqua, Wisconsin. So this event and some of the events that we've had over the past couple of weeks have really sought to prepare them for those, for those experiences. The point I'm trying to make, though, is that the urban rural divisions that we'll be discussing today are very real here at Stanford and at other elite colleges and universities.

This lack of representation and connection may have something to do with the fact that according to Gallup polls, the Pew Research center and others, confidence in post secondary institutions has declined quite precipitously in the last decade. So today's I couldn't be more thrilled to introduce two scholars who have both very deeply looked at and explored geopolitical polarization.

I didn't have to go too far to find the first, the perfect local person to join this conversation. And I mean that quite literally, he's in the office next to me. Jonathan Roden is a professor of political science in Stanford's School of Humanities and Sciences and a senior fellow here at the Hoover Institution.

Jonathan's 2019 book why Cities Lose masterfully uses data from across the 20th century to show why cities lose to rural and suburban interests and how that actually harms democracy. He was recently named the A2025 Andrew Carnegie Fellow by the Carnegie Corporation of New York, an honor that recognizes his national leadership in research aimed at understanding and addressing political polarization in the United States.

He served on faculty at MIT before coming to Stanford in 2007 and is also a Senior Fellow at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research. Thank you Jonathan for being a part of today's conversation. Nicholas Jacobs is an Associate professor of Political Science at Colby College. His research focuses on federalism, rural politics and public policy.

Nick and his colleague Daniel Shea have written the Rural the Politics of Place and the Disuniting of America, a contribution that our own Mo Fiorina, who's also here today and also an enormous has made enormous contributions to our understanding of polarization and party sorting. Mo has said that this work is one of the most comprehensive studies of rural voters ever produced.

Nick is the inaugural Director of Colby College's Public Policy Lab which seeks to rebuild trust in government, elected officials and experts by providing students with real world experiences through internships, partnerships and hands on experience with research across public policy related issues. Nicholas is a native of Virginia and studied Political Science at the University of Mary Washington and earned both a master's degree and PhD in government at the University of Virginia.

It gives me great pleasure to welcome Nicholas to the stage. Thank you.

>> Nicholas Jacobs: Well, thank you so much for the opportunity to be here and to speak with you all today. This is the last thing I have to do. I've signed for my supper and I've just had a tremendous visit.

As Tom mentioned, I've spent a lot of my time talking with Stanford students. It didn't take much for him to convince me to come out here. After he told me about this fascinating new fellowship program that RAI is starting. I spend a lot of my time wrestling with the question, can anything be done to overcome the rural urban divide?

It's a serious divide. I think it matters. I think it's problematic to our politics. And like most things that are truly problematic and serious, there is no panacea, there is no nothing simple that is going to solve it. I think it's only gonna happen on the margins. And I think this is an important initiative.

And so what I wanted to spend my time doing today is explaining why I think that's an important thing that we should be trying to solve. Why this growing political division between rural and urban areas that we're becoming so accustomed to seeing every four years when the big map is put up on election night is problematic in our politics.

This project is a couple of years in the making. In 2020, with my colleague Dan Shea, who's also at Colby College, you're sitting around talking probably about our homesteads. We both live in central Maine. He boils sap and I try to grow things in a climate that is just inhospitable for growing anything.

And we realized that there was a lot of anecdotal evidence about this thing called the rural urban divide. And notwithstanding an excellent book that had been published the year prior to, there wasn't a whole lot of evidence centered on the rural experience in the rural urban divide. And we set out to do two things.

First, we attempted to understand this problem historically. Is this rural urban divide anything new? Perhaps it's the case that our institutions have weathered this storm before. Maybe this thing we see with red states and blue states and sparsely populated states in between is actually all just measurement error.

Can we really start to wrestle with this question of how recent the rural urban divide is? And so we go all the way back to 1824, constructing a large geopolitical electoral data set. I'm gonna present some evidence on that in just a few minutes. And then we supplemented this with the largest survey of of rural voters, a single survey of rural voters on rural issues ever conducted over the course of three years, gathering close to 10,000 unique individual survey responses.

Again, the questions from this rural voter survey are going to inform most of my presentation today. Like a good social scientist, and for students in the room, take note that you're writing your final papers. I'm not gonna give you a mystery novel. I'm gonna tell you who I kill, with what weapon, in what room right away.

There was a chance that in doing this we would have found that the rural urban divide is not a thing. That the division we see every four years on the electoral maps was nothing more than a function of the fact that rural areas are older than average, are wider than average, a function of its demographic composition.

There was the possibility that the rural urban divide was nothing new. Now we've seen it in the late 1800s, like the populist agrarian revolt. We see it in the 1960s as in George Wallace's insurgent campaign. And we were comfortable with that idea. That's not what we found. We found that there is something distinctive about rural voting.

There is something distinctive about the rural voter. That's not to say that demographic composition, the fact that rural areas tend to have a lot of the demographic stuff that makes them vote more conservative doesn't matter. The racial composition of rural areas, which are overwhelmingly white, the education composition of rural areas, which tend to skew less than college educated, those matter.

But ruralness is not reducible to the sum of its demographic parts. What we find again and again is that there is something distinctive about ruralness that has drawn people to think about politics differently. And then what I'll elaborate on in the next couple of minutes is the idea that rural voters are distinctive from their fellow Americans in how they think about their place, their community, their neighbors.

The ways in which they orient their political worldviews around their place in a town, and how that orientation ultimately leads to a feeling of grievance and being looked down upon by those who don't inhabit or come into rural areas nearly as often as rural people go into urban areas.

Dan and I call this a place based identity, or specifically a rural identity. And by identity, I just want you to think for a moment about all the identities you have. You're a member of a profession, you're a member of a racial group, you're a member of a class.

And a lot of people do have a place based identity. A lot of people feel connected to the place in which they live. But for rural people, this place based identity informs their politics in the way that your membership in a racial group or your profession may inform your politics.

It's this connection to place that has an explanatory factor in rural partisanship. So with the time remaining, I just wanna work through three questions that you might be having that I hear all the time and how this place based identity might help explain the answer to some of these questions.

The first just expose the elephant in the room. Isn't this all just about Donald Trump when you talk about the rural urban dividend? Quite frankly, nobody really talked about the rural urban divide prior to 2016. Maybe this is just Donald Trump's doing. There is something to that fact.

There was no Mitt Romney house in rural Pennsylvania like there was the Trump House, sites of pilgrimage for rural people to go to in the countryside during the campaign. My neighbors didn't paint McCain on the side of their barns. There was something about Donald Trump in rural areas.

I don't deny that. But when placed in larger historical perspective, I wanna point out a few things. So this is the percent of the presidential vote for the Democratic presidential candidate. In urban areas, we can talk definitions in the Q&A, and in rural areas going back to 1824.

The first thing I'd like to point out is that year over year throughout this country's history, rural and urban areas have largely moved in the same direction, even in periods that we tend to associate with rural unrest and sort of rural insurgency. It's only in the 1980s when we start to see this divergence in partisanship open up.

This is the percent of the vote for the Democrat in rural areas and urban areas taken as a whole. And there's actually very little regional variation, something I'll admit I was surprised to when we set out on this study. Let me transform the visual just a minute to better make this point.

Part of the difficulty in looking at vote share over time is you can imagine sometimes candidates just do better in some years than they would have if they had a worse opponent or a better opponent, right? When Ronald Reagan wins in 1984 in a landslide, it's not like the Republican Party became super popular in the course of four years.

There was some campaign specific contextual issues. So one way we can get some better leverage over change over time is we look at the relative over or under-performance of a candidate in a given year. So you sum up, how well does the Democrat do in a given year and how much did urban areas over perform?

That's above the horizontal line. And how poorly did rural areas underperform? You can see we still have a similar gap. But one thing I would take note of this gap and the continual underperformance of rural communities since 1980 is that if you were to draw a line between 1980 and 2024, it's nearly linear.

And Donald Trump overperforms or Hillary Clinton underperforms in rural communities just a little bit more than she should have given this decades long trend or decades long hemorrhaging of rural votes for the Democratic Party. So I think there is something about Donald Trump, but I don't think this rural urban divide exists just because of the Donald Trump.

And I hate to tell you if you're nervous about this, I don't think it's going away once Trump goes away. So at the same time that this is going on, you might be thinking, and you might already know, rural areas, the American economy in general is going through a dramatic transformation in its economy from 1980 to 2020, even today.

Well, let's not say today, let's say within the last 200 days, right? This is the period of economic liberalization, globalization, the exodus of manufacturing, which if you don't know by 1970, a majority of manufacturing jobs are no longer located in the middle of a large urban center, cities next to the railroad tracks.

I can't believe I'm saying this in front of the guy that taught us all this, right? Manufacturing is a rural phenomenon by 1970, the majority of our manufacturing capacity in rural areas off the interstate, where land is cheap and labor is too. And so you might be thinking, well, maybe this is all just about that.

And there's something to that as well. So I'm just gonna narrow our time horizons ever so slightly and look at just the last two decades instead of the last four. And here, what I just want you to take a look at is we're gonna look at the change in employment before and after the 2008 financial crisis.

So if in 2006, we counted up all the jobs and we said, here's how many jobs relative to the population are in rural areas. Here are all the job in big cities, and here are all the jobs in small cities, and relative to that starting point in 2006, here's where job gains have increased, and here's where job gains have decreased.

You can see everybody in the financial crisis suffered. Some places suffered a whole lot more. In the immediate Aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, some places recovered their jobs quickly. Rural areas never did. In fact, it was just in the last couple of months that rural areas finally recovered their base employment relative to the start of the COVID 19 pandemic.

There is something to the fact that these places have disproportionately borne the brunt of this economic restructuring. But the rural urban divide is not reducible to just that. As you likely know, when we're trying to think about larger political trends at a national level, we can use the demographics of the population to make sense of it, right?

We know that if you're a woman, you're a little bit more likely on average to vote for the Democratic Party. We know if you have a college education, you're more likely on average to vote for the Democratic Party. Up until very recently, if you made over $100,000, you were a little bit more likely on average to vote for the Republican Party.

Remember James Carville and the famous saying, it's the economy, stupid? If you wanna know how somebody's going to vote, you ask them, are you better off now than you were four years ago? Those demographic explanations do not help us explain how rural voters, and this is bar charts of just rural voters voted in 2020.

But it's also true in 2024 and 2016. Whether or not you made below 40,000 or above 90,000, you were equally likely to vote for Donald Trump in a rural community. If you had a job, if you didn't have a job, if you were better off, if you were worse off.

Take a note of the college education and the lack of explanation that college degrees fail to have in rural communities. There's a little gap between those in rural areas that don't have a college degree and those that do. But the majority of rural residents with a college degree will vote for Donald Trump and that is not true on average nationally.

Standard demographic explanations do not explain it, but something else does. Rather than asking whether or not you were better off than you were four years ago, Dan and I found that another type of question does give us some leverage on predicting vote choice. Whether your community was better off than you were four years ago.

We find there were multiple questions that the attitudes that have the highest discriminatory value in helping us predict whether or not somebody in a rural community is going to vote for Donald Trump is their sense that their community is worse off, that their community has less of a future than other places in the country.

We find that gaps between rural and urban areas on questions, my kid is gonna have to move away in order to live an economically productive life. People look down on what rural communities have to offer. And yes, a majority of Americans say that government doesn't listen to urban people or rural people, but it's consistently higher nationwide across rural communities.

One of the reasons, and I'll admit it, is something that I think is deserving of a lot more research. One of the reasons we think this to be true is also rooted in the geography of rural areas. Rural areas, as it turns out, are vastly more socially and economically integrated places than cities are and the suburbs are.

And by integrated, what I mean isn't that they're more racially diverse, they're not on average, but that you are much more likely to live next to somebody of a different social or economic in a different social or economic circumstance than you are. Let me just zoom you in and take you to my country road in central Maine.

Every day when I drive to work, I drive past the nicest house on my street. It's not mine, the nicest house on my street. And it sits right across from the least nice house on my street. And when I say least nice, I can actually say this now because they finally finished fixing the roof after three years.

Their kids go to the same school because there's one school in town. They both drive on the same potholed roads because that's the road in and out of town. They experience the same government. They interact in the same social circumstances. In the lead up to the last election, I knew none of my colleagues who drove by a house in foreclosure.

I drove by three every morning. You see a different world, even if it isn't your own personal world. I also can't believe I'm saying this in the room with somebody that taught us all that our tendency to overstate the prevalence of culture wars also fits into the answer of rural poverty and how people see the world.

Because oftentimes we see that, if it's not the economy, if it's not the economics that are cleaving people into the two different parties, it must be their positions on social and cultural issues and what we find depending on no matter how you ask the question. With very few exceptions on policy or value or social issues, there are few things that fully separate rural and urban people.

This is not the land of anti-abortion extremism. Similar percentages of rural and urban Americans have the same attitudes on whether or not abortion should always be made illegal, okay? There's actually surprisingly similar economic progressivity. We do know, I just know from work I've done earlier in this year that this is rapidly changing the agreement on whether or not kids should go to college.

But at least three years ago, when we were taking survey measures of this, the gap wasn't so wide. There's no gap on sexism, there's no gap on ethnoracialism. There is a gap on racial resentment. And the other big policy issue is there is a big gap on guns.

But with few exceptions, the culture wars are not being waged. So the third question I often get is, all right, so they have this more socially oriented way of thinking about the economy. The shift is decades in the making. But if all that's true, why on earth don't rural people reward the one party that's trying to do anything about it?

Why do rural residents keep voting against their interest or failing to reward the Democratic Party who's giving them or delivering to them, as the Democrats like to say, say the last four years, the goods. And here you have some broadband cable because that's the example we always use.

No doubt about it, given the structure of our welfare state, also just given again cheaper land prices, so the government finds it more affordable to put projects in rural or red areas. Rural areas have been on the disproportionately high receiving end of recent federal investments, including the major investment programs from the Inflation Reduction act and Biden's CHIPS Act.

So this is the Trump vote margin. It's not exactly rural and urban, but this is rural, and this is the Biden vote margin. It's going overwhelmingly to districts that actually voted against these policies. What I find interesting is that this is where usually the conversation ends. When you start asking rural people about these programs like we do, you start to dig in to the reasons why this policy of deliverism we're gonna give them the goods, or bidenomics begins to fall a little flat.

First, we see that a lot of rural Americans just tell us that these programs like infrastructure or broadband are just not as important to their daily lives as urban people do. I just wanna point out that when we talk about rural programs, it's almost always urban policymakers telling rural people that these are the things that are good for them.

The other thing that takes place is that rural people are vastly less likely to have heard of specific investments in their communities. Now, part of this has to do with the way these programs are often implemented in rural areas, which I'll get to in a minute. But the other reason is also rooted in geography.

Although a disproportionate amount of small spending has flowed to blue districts and urban districts, nearly every city large city in America has received some form of investment, although disproportionately high spending has gone to rural districts. Because of the geography of rural areas. Fewer than 5% of rural communities have been the recipient of a specific investment from these projects.

The other thing is that when you ask rural residents why isn't this important? They're drawing on a place based identity which tells them that this money is actually not more likely to go to them, it's not likely to benefit them. And they're drawing on an identity that informs a resistance to government at almost every step of the way.

You ask them, well, why isn't infrastructure important? It's because the government has bad intentions. You say, why is broadband not important to your community? They say even if the government has good intentions, it usually makes things worse. Almost two-thirds of rural Americans will agree to that question. And I think it's often overstated.

I agree with that. But I know that every rural community I've ever traveled to also has a story that seems to validate that perspective, that hears about broadband spending like the $42.5 billion in the bead program that three years later hasn't hooked up a single rural household. So you can't end the conversation with Congress appropriated money, it's hard to do that work or the big new factory, the 7.86 billion dollar factory that's going on in rural Ohio that's going to provide 3,000 jobs.

I mean, we could debate whether or not that's a good cost benefit, but what we do know is that those 3,000 jobs are actually disproportionately going to go to people outside of that community because of years of under investment in local public education systems. Because vocational education training programs have been basically stripped from the curriculum that companies like Intel will have to bus in employees who will then raise housing prices, increase property taxes and put a strain on local communities.

Or in my neck of the woods, farms that are suffering from an environmental policy decision made 40 years ago when the Department of Environmental Protection said the don't worry. This sludge that we are giving to you free of charge to spread on your hay fields, it's safe. And we've learned now that it's not.

It's a public health disaster. I don't want my kids drinking my well water with PFAS. But I also know and can understand or empathize with farmers that say there's surely no way I'm testing my well water because as soon as they find an ounce of that, they're shutting me down.

And this trade off between public health and community health is not a discussion, a difficult one we often have. So I'm at my 30 minutes. But I have a bonus question. I'll end on this. I often get the final question, all right. So even if your rural identity framework is true, even if they're more likely to think sociotropically or about their community's orientation, and even if there's some real challenges and missed opportunities in the deliverism policy model, aren't rural voters a threat to American democracy?

Or as Paul Krugman at the New York Times likes to write about every other year, isn't there anything that can be done to assuage this rural rage? And I'm not sure why this rage and rebellion trope has taken off so much. Maybe it's the last vestiges of the stories and stereotypes you're all too familiar with of yokel up in the hills with shotgun, steaming mad and probably drunk.

Because I do believe that rural people are the last group of people you can stereotype in polite society. Cuz I don't see rage. I haven't seen any rage in all the rural communities I've traveled to across the country this past year in the middle of an election cycle.

I don't see rebellion. I don't see anywhere in the data support for anti-democratic principles. And I get what you're saying, survey responses, or even to push you more, I hear what you're saying. I don't care what they say on a survey. I don't care if we have more in common than what I'm often told.

They voted for a man who I do believe is a threat to American democracy. They willfully invested power in a man that I feel is eroding democracy in this country. I think that's a valid argument. It's a valid argument even if everything else I've said has a kernel of truth.

If you believe that to be true and if what I had said has an ounce of truth, that there is less that divides us than we might think that there is a legitimate or sort of rational worldview that informs their politics. I'd encourage you to think through the fact that you have a choice.

We have a choice in an elite level, at a campaign level, at a strategy level. We have a choice at a mass level how we think about this on an individual in our day to day lives. You can write off 20% of the country as irredeemable as a threat to American democracy and we can suffer those consequences.

Or we can recognize that there is room for engagement, that these are our fellow Americans who have not given up on the promise of liberal democracy. They simply wish to restore a version of liberal democracy that seeks to restore the equal worth not just of every individual, but every place in this big country of ours.

And with that, I'll end on a happy note, my wonderful two sons and their adorable overalls. Thank you very much.

>> Jonathan Rodden: So thank you all for coming. And thank you very much, Nicholas, for joining us. I've been really looking forward to our conversation and I have lots of questions I'd like to ask you.

We'll see how many of those were able to get through. First of all, I just wanna thank you for all the work you've done and trying to trying to bring some reality to some of the misconceptions about rural America. I was not one of the people that raised their hand at the beginning, but I did the next best thing.

I married into a rural family. I spent a lot of time in rural Michigan every year and have become very interested in all the same questions you're interested in. You mentioned the book that I wrote earlier. In some ways, that book was really focusing on differences between urban areas and everyone else.

And in some ways you are looking at the other side of that and trying to understand what it is that's distinctive about rural areas. And we're both kind of leaving the suburbs in the middle. And there's still a lot perhaps to be said about, about the suburbs. I think these places, there are ways in which I think there are some issues on which rural areas look a lot more like suburbs.

And I think economic preferences might be in that category, whereas there are some other ways in which rural areas are very different from suburbs. And some social questions about gay marriage and religion and abortion might be in that category. So one of the first things I wanted to ask you about, I think you've done a really good job of explaining to folks your thoughts on the importance of a rural identity and a place based identity.

And that's one of his real contributions with some of his collaborators in the academic literature, is to just convince people that such a thing exists and to try to measure it and try to do a lot of work in surveys to understand what it is to have a place based identity and to try to convince us that it matters.

I wanted to ask you a little bit more. You gave us some data to suggest that it's not reducible to the sum of demographic parts. So it's not just that rural places are different and that they're whiter or that they're older or less, less likely to have a college degree.

And then you gave us some evidence to suggest that on some issue questions, later on in the talk, you talked about some issue questions on which it doesn't look like there are very big differences between the places. But in some of my own work, I guess one of the things I wanted to push you on is that it seems like there are some economic and especially social questions on which rural places do seem to have distinctive preferences.

Immigration is one. Maybe not, there are certain kinds of abortion questions where they can look similar, but there are others where I think they look a little bit different. And there are other questions about a broader set of issues related to gay marriage and moral values more generally, where it looks to my eye like there's a difference between rural areas and suburban slash urban areas.

And so one of the ways I've thought about this, and I wanna see if you can kind of correct me, one of the ways I've thought about this is that in 1976, if you didn't like abortion, it wasn't clear which party you should vote for. But by 1980, by 1984, it was very clear.

And so if you were somebody who had strong preferences on these issues, and if we think preferences are correlated with population density on these issues, then once the Republicans start to politicize abortion and those other issues. Then if people in cities and in rural areas start to realign based on their preferences on those issues, then we'll start to get some urban, rural divide and the same thing later on with immigration.

We could think about race, environmental protection, a few other issues that as the Democrats take one set of positions and Republicans the other. And if people realign on each of these, then we would kind of get the patterns that you see in your data without any kind of identity component at all.

And I believe you that there's an identity component, but I'd like to hear you explain how do we know that it goes beyond just these issue preferences and that there's something there that really is related to identity?

>> Nicholas Jacobs: Yeah, so there's a few ways I'll tackle this really thought provoking question.

I mean, the first is maybe just to take a minute and explain a little bit more what we mean by an identity. And I guess the first thing that comes to my mind in wrestling with your question was something that Dan and I wrestled with the whole project.

I mean, are we just talking about white rural conservatives? This is I think to the point like maybe this is just about some people being more conservative and having happening to live all in one type of area. Maybe conservatives are just drawn to wide open spaces, I don't know.

We do not call our book the white rural voter. We never, with the exception of one chapter to demonstrate this fundamental point, break these gaps up into white rural people, non white rural people. Cuz we actually find through this identity framework that when it comes to issues of grievance towards government, a feeling of culturally like a way of life feeling looked down upon and a sort of a sociotropic like outlook on the future.

Black rural residents have that in common. Latino rural residents, who are the largest growing racial minority in rural areas, actually they are the reason why rural areas grew within the last ten years. They share these hallmarks of rural consciousness or rural resentment, which I think is some powerful evidence to the idea that there's something about the rural perspective that's shaping people's views now.

It doesn't always shape their votes. One of the interesting findings, for instance, is that we know that rural resentment among black rural residents is pretty high. But the more rurally resentful you are of black, the more likely you are as a rural person to vote for the Democratic party.

So it skews the politics getting a little bit deeper on the identity framework. Ultimately, I saved the regression models for the book, and 55 other charts, I can't get through all of them today.

>> Jonathan Rodden: Yeah.

>> Nicholas Jacobs: But in the book what we try to do is we try to build a model of predicting one's sense of reality.

And the answers to these issue questions, traditional social conservatism and some of the other ones that surprise us, religiosity, patriotism, these issue preferences have zero predictive value in understanding whether or not somebody is either rural or holds these other hallmarks of rural identity.

>> Jonathan Rodden: Let me ask you a related question that is a little unfair because you can't go back to 1980 and interview people and ask them all the questions that you've dreamed up in the recent years.

But some of the aspects that you describe of rural identity strike me as things that probably existed in the 1980s. That people had some of these views about the importance of place and family and rootedness. These are not new concepts at all.

>> Nicholas Jacobs: Right.

>> Jonathan Rodden: And so, and I think what you say in the book, and I just wanna give you a chance to articulate that, is that this is in a way a kind of a latent thing that had to be crafted.

In the same way that I said that abortion or moral values had to be activated by politicians. You kind of tell a story in the book about the activation of this notion of place, that it had to be in a way sort of crafted. And cuz you could imagine either party could tap into that set of feelings.

How did that come to be?

>> Nicholas Jacobs: Actually, I like the way you frame the question too. And it's having me think, I think this was a part of American political discourse more broadly. I mean, famously, all right? The most famous book, maybe the second most famous book ever written on Congress talked about every member of Congress had a home style politics.

This is how they would continually win re-election. They'd go back to their districts and they'd speak a different language, a local language, a language rooted in place. And I think both parties did this. I am sort of increasingly drawn more and more to the idea that it wasn't that.

And this is a little change from the book. One is allowed to change their minds. In the book we write about how some of this was a deliberate strategy on the Republican side to sort of start speaking the language of real America. There's a reason they picked Sarah Palin in 2008 from Small Town Wasilla.

Hockey moms, that sort of cultivates an image in direct contrast to the urbane Barack Obama. But it might just also be the fact that Democrats stopped using that language, right? That the Democrats of the 1980s were equally likely to speak that language, to have that home style. And then for a variety of reasons, a set of overdetermined phenomenon began to tack different course.

>> Jonathan Rodden: Great, well, I think maybe we'll come back to that. Maybe some audience questions will be about this as well. I think, one of the things that a lot of people will probably want to ask you is to what extent is this reversible and how can it be done?

And maybe we'll come back around to that.

>> Nicholas Jacobs: Thanks for priming them with the hard questions.

>> Jonathan Rodden: I mean I wanted to talk a little bit about this business of materialism, interests and what's the matter with Kansas and that sort of thing. And I think, well, I wanna push you to maybe clarify a bit better or respond to something that I've been thinking.

You start off by saying, well, it's not really quite poverty in the way that you might think. And there's this really different sort of, I think it's fascinating what you're saying about lower levels of income-based segregation in rural areas, which is almost certainly true and I think really important and there's more to be done to understand that.

But I wanna get to this something a set of arguments has really been out there in the academic literature and also in the popular press, not just in the US but in Europe, Canada, other places that there have been some big economic shocks. And so there's been a big literature on the China shock, the entry of China into the WTO and, and the import competition from China and the way that's affected rural America.

So some papers by David Autor and others and then there's been recent work in the US on NAFTA, part of it by Gavin Wright, an economic historian here at Stanford, on the shock that NAFTA posed for many rural places. The way in which this affected rural communities, even beyond those just kind of globalization more generally and the way it's shaped manufacturing and employment in rural America.

And so there's a narrative that it's these economic shocks that really did that that are really the big story. And that in that story seems a little less consistent with this identity based story you're telling. And I think I hear you pushing back against in a way, I think your story does have a big economic component, but I think you're also pushing back to it in part.

One thing I've recently noticed that if I just take county level data and I look at the correlation between population density and Democratic voting and I divide the counties up into income quintiles, that the correlation is the same in each of those quintiles. So, that county level income is sort of the urban rural divide is there at all levels of income.

And I think that's very consistent with what you're saying. So would you draw from that this whole left behind business is actually not really that important or would you push back?

>> Nicholas Jacobs: I think it's tremendously important. I think it shaped a larger national narrative of what it means to be rural, not just in an economic sense, but in a cultural and social sense.

So I think it's incredibly important, but for the exact same set of empirical patterns, just differently. I mean, I recognize that, and this is a paper I just finished up last week before coming here, that in some parts of the country, rural areas are vastly outperforming their nearest urban neighbor.

I in fact live in one, that on average my county is poorer than the national average. So that absolute value matters. And that absolute value is a part of my current county's history, not so much China shock as much as agricultural consolidation. A little bit of that is international agricultural commodities, but neither here nor there.

But compared to Waterville, compared to the mill towns up and down the Kennebec river, which are urban by main standards, these rural areas are doing comparatively much better. The schools are better, the housing prices are higher, the government's relatively better funded. And that's just an example. It's true throughout the country.

Rural Montana, it's hard to get a home. Rural North Dakota is actually comparatively doing pretty well. And so these arguments about it's the places left behind, it's the places that suffered the brunt of China shock and China's entry into the WTO, I think it explains some of it, but it doesn't explain why this is happening everywhere.

And that's still the aspect of rural politics that I try to wrap my head around the most is why given the vast diversity of rural America, and I was just talking with Rural Club last night. It's immensely diverse, topographically, economically, racially, I mean, the rural south is nothing like the rural Northeast.

My co-author and a bunch of projects laughs at my five acres. He grew up on 5,000. But the shift in partisanship has taken place everywhere. And I think when you see something at that scale, it has to involve narrative. It has to involve the stories that people are telling themselves as well as the stories that politicians are telling them about who they're for and who they're against.

>> Jonathan Rodden: Great, I'm sure we'll have some more questions about that. I wanna move on to another, another thing you talked about, which is people's reaction to government, reaction to the state. And one of the things that we hear I think from urban residents a lot is, if you made a scatter plot of population density and we know now that that's correlated with Democratic vote share, it's 0.9 or something.

Usually you take a scatter plot of population density. And transfers the individuals as a share of income, is a very, very high correlation between rural residents and transfer dependents. Also myself, have looked at some public employment. So because of the departure of the private sector that you described, many rural places, public sector employment is something like 20 to 30% of employment.

The largest employers in many rural places are school districts and hospital systems. And so there is this strong dependence on government, if you will, that is combined with a great mistrust of government. And I think part of your response to this, I mean one very interesting claim that I hadn't really fully thought of before is that it's really hard to spend enough money to really affect lives in very sparse places.

It's a pretty obvious point, but I think it's worth driving home. But also there's just this kind of, this experience with bad outcomes. I mean, I think the quip from Reagan about I'm here from the federal government, I'm here to help. And being this kind of scariest words in the English language I think really resonates and I hear that a lot in rural America.

People really like that quote and it really. It really means something. And so is your take that this is kind of based on just a lot of failed kind of programs historically. And then I guess there's a kind of related question about in addition to that scatter plot that I just described.

Another one is that there's a real concentration of investment in colleges and universities and research and things like that in urban places and that that might create some pushback and the sense that we're not getting our fair share when it comes to that kind of expenditure might be quite justified.

So I guess that's two questions.

>> Nicholas Jacobs: Yeah, I kind of in response to both at the same time, I think it's important, I think we all do this. I think, I don't know if it's human nature, but like we care about the absolute value of the thing we do get.

We also care deeply about the relative value of the thing we get. And so I do think this question of fairness FA plays into it quite a bit. And I don't think anybody, except for maybe you and me, Jonathan, walk around with scatter plots of density and income transfers in our back pockets, I-

>> Jonathan Rodden: Yeah, these are not things that are known, but I guess are they felt and kind of-

>> Nicholas Jacobs: But yeah, related to that, I mean wherever I go, you hear stories of some bad policy. We talk all the time in political science about how ignorant voters are and they don't know enough and they're ill informed.

I can tell you related to the previous question that in those old mill towns right throughout the agricultural heartland, they know five letters NAFTA, they know a policy. So there is a story and I do think you hear this story frequently and I just tried to give you a flavor of two.

One was sort of a non story that we were told about broadband. That was a story that rural communities have experienced. Now that doesn't answer what I do think is a very difficult question of okay, there's been some bad government policy. Government's messed up. Government messed up in urban America too, right?

Governments in urban America has plowed highways through poor black neighborhoods, took away coastlines. There's been government failure in a lot of places. It still doesn't answer the question why if you are dependent on government, right. Rural places are disproportionate beneficiaries of Medicaid. Why you would vote for a party that wants to cut Medicaid or why you wanna vote for a party that wants to put work requirements on Medicaid knowing that it's gonna be an administrative burden to travel hours to the nearest office to demonstrate your Medicaid eligibility.

That is a good question. I talked to my neighbors about that. I do survey work on that. And the best answer I have is it is already such a shitty system, for lack of a better word, that rather than trying to put lipstick on a pig, you try to change it entirely.

Nobody wants to be dependent on government. And so I get, and I sympathize and there's a lot of, I don't think think rural people actually voted to slash Medicaid. But I also think they voted for change and are tired of a system that only permits them dependency on government and intergovernmental or financial transfers and aid rather than real opportunity.

>> Jonathan Rodden: I think that's right to note that a group is dependent on government and then say that, well, they should be thankful voting for the party that wants to provide more government. I mean, it's a gotta be a lot more complex than that. And there's a sense that they want private sector employment, they want jobs, they want something other than dependence.

And that that's probably a good way to think about those scatter plots and what it might be behind them.

>> Nicholas Jacobs: Well, I would just add it's a fair question, right? I often think it's the wrong question. It's, to be frank, not to be like, I don't know what the word is.

It's the question that our representatives, and let's just call them the political elite want us to ask. Cuz what I know to be true is that when rural voters were given the chance to vote on Medicaid expansion in their state directly by ballot, they turned out and they voted to expand Medicaid.

When voters in rural communities were given the choice to adopt school voucher programs, they overwhelmingly rejected it. So I think it's a fair question. It's a really hard question. But I think, every minute we spend answering that question is a minute I'm not answering why their representatives are allowed to get away with this stuff.

And that's why, I mean, in the book, that's why I ultimately describe it as an institutional problem in the It's a problem of our politics and our political system that I don't think is solved. When the Democratic Party just says we can't compete, we can't convince them. That's what allows the representation gaps to fester.

>> Jonathan Rodden: You mentioned school vouchers, and it was an area where I wanted to ask you a question about heterogeneity and the Republican coalition. Where one of the things that's happened is that as rural places have lost population, they've also become much more Republican, which has only made the Republican coalition more heterogeneous in a sense.

And so there are these brewing battles within the Republican Party between, some of which are urban, rural in nature. So I'd love to hear more about that. But I think if we do that, we might not have time for questions. And it seems maybe that'll kind of come back around one of the questions.

But I think it's time for us to take some questions from the audience. And so we would ask that you don't start asking your question until they come around with the microphones. And I will call upon people. And it looks like Mo Fiorina is gonna go first. We have to get the microphone, Mo, play by the rules.

>> Speaker 4: Just an observation. The picture of the Trump house that used earlier, that's my cousin Leslie's house.

>> Nicholas Jacobs: No way.

>> Speaker 4: Yeah.

>> Speaker 4: Yeah, first cousin Leslie. And she did that in 2016, and she registered 20,000 people. That house is full of computers, Internet connections and so forth.

She probably carried Pennsylvania for Trump.

>> Nicholas Jacobs: My goodness.

>> Speaker 4: And it was a source of amusement in the family that her mother, my Aunt Vera, would not speak to her the whole campaign because Vera is a dyed in the wool Franklin Roosevelt Democrat.

>> Nicholas Jacobs: Right.

>> Speaker 4: And the idea her daughter was working for Trump was, that's like setting foot in the Protestant church, you just don't do that sort of thing in the family.

More substantively, Jonathan, you talked about Republicans adopting positions that might have widened the urban rural gap. I think the most obvious candidate is the environment that in the 1970s, both parties are struggling to win the environmental vote. The Democrats do. And over time, I mean, the Democrats, they're opposed to logging and ranching and agriculture.

Not opposed, but they're skeptical about these things. A lot of things are the economies of these rural areas. They don't like you to shoot things. I mean, there's just lots of reasons. I believe in a rural identity. I've lived my life in Cambridge, and here. And there's still some ways I don't fit, but, but nevertheless, I think there's good substantive reasons why rural people also turned against the Democratic Party.

>> Jonathan Rodden: Yeah, I think this is, I study also European politics and this is something that, I mean, this is why we have green parties in Europe. So, this is part of what got folded into the Democratic coalition and our two party system. But in Germany, or the Netherlands, we have a separate party.

And this is part of why ruralist parties are really gaining strength in the Netherlands today and part of why populism is growing in the Netherlands because of some of the environmental policies that have been implemented by Green coalition in the Hague, has really affected people's livelihoods in rural places.

>> Nicholas Jacobs: So there's a certain senator who has presidential aspirations from the great state of Minnesota, when I've talked to her about this, she says, well, I just talk about one thing. When I'm in northern Minnesota, I talk about the wolves and I complain about the wolves. Marie Goose and Camp Perez, when she's out in Washington, talks about the spotted owl, these are parts of the stories.

And I tend to, I think cuz of what I study and where I live sort of in my priors, I'll be honest emphasize the stories of Pollus, good intentions gone bad. But some of this is intentionality and good policy. They brought back the wolves, they saved the owl.

And I think you're right that the environment fits into this in complicated ways. Before this talk, I was having lunch with the students that are going to rural communities. And half of them study environmental issues. And very similar to my students at Colby, they're very environmentally conscious. They care about this earth.

They wanna be good stewards. They all drink paper straws and have electric vehicles. And I challenge them, I said, the thing that you are going, one of the things I want you to learn about, because it is something that we are still studying and doing work on, it's the frontier of research, is how this identity shapes rural individuals connection to the environment.

Because I guarantee you any rural community you step into, you will meet people that are more in tune with nature than most of the people here in this beautiful idyllic setting. Who live for one month out of the year when they can go into the woods and hunt and yet would be caught dead driving an electric vehicle and would deny the fact that humans are causing climate change and Again, I guess we have a choice.

We have a choice as scholars. We have a choice as individuals and mass democracy, do we write those people off as being duped by Fox propaganda or do we try to understand the ways in which they experience the world differently than we do? And I'm gonna make one choice.

>> Jonathan Rodden: Can I ask you put a wolf question on one of your future surveys? I think it's incredibly powerful. I can't believe how often it comes up in my conversations with rural people.

>> Nicholas Jacobs: Yeah, especially in Michigan where you go in Minnesota.

>> Jonathan Rodden: Really very high, it's a very high.

>> Nicholas Jacobs: So endangered species.

>> Jonathan Rodden: Places where it's not really very, very even in the neighborhood, but it's just something that people are very reactive to.

>> Speaker 5: I don't know if this supports your argument or not, but looking at your graph that you started at 1980. If I blank out Ronald Reagan, it goes back to the 1940s and then contributing to the argument.

Democrats were Jimmy Carter 76. Don't get more rural than that. And is this a response or not? And is this a much longer term trend?

>> Nicholas Jacobs: Democrats do not win the White House after FDR unless they have a Southerner on the ticket. Barack Obama in 2008 is the first Democrat on, FDR had Southerners on the ticket.

So that's not even true, right, but that's sort of a different story. I mean, Democrats remained regionally balanced. The south looms large in the narrative of rurality. The south is only about 40% of the American rural population. 45% of the rural population sort of has an outsized influence on the way we think about ruralness.

Sometimes we talk about the Southernification of rural areas. I saw more Confederate flags in central Maine than I did living in western Virginia when I moved up there. And some of this when you're going to the historical patterns and thank you for the question. So some of this is tied up with that larger regional realignment and the Southern realignment to the Republican Party and it matters because of the large percentage of rural people in the South.

Two quick anecdotes. Franklin Roosevelt is often viewed as a president for rural America. His policy is the New Deal has a strong rural component, modern agricultural policy is born of the New Deal programs that come out of the first wave of the New Deal, like the administration and Agricultural Adjustment Act.

He loses all the gains in rural areas almost instantly. There is no sort of transformation of the Democratic coalition and rural communities after this sort of sharp uptick in 1932, Lyndon Johnson in 1964 in fighting the war on poverty. Lyndon Johnson is from some of the most barren and desolate parts of eastern Texas, was a youth leader in the youth corps for Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal, and wants to be the president of rural America.

I was a fellow at the Johnson Library and I found a memo where he was actually complaining to Arthur Schlesinger. Why do people call me the President of the cities? Why is so much of the Great Society wrapped up with urban imagery? We've done so much to obliterate rural poverty, but rural areas still had an allegiance with the Democratic Party.

It wasn't so heightened disparity. It really is in 1980 that it's not as wide in 1980 as it is today, but it starts to take off.

>> Jonathan Rodden: But I would point out that if you look at your graphs that in the New Deal the solid line and the dotted line did diverge.

The urban places, that was kind of the beginning of the urban rural divide. I think Maybe it was 1928, but it really took off in the New Deal not because rural places became Republican, it's because the urban places became very Democratic and that they stayed that way for a long time.

And so, I think we're gonna still agree that in 1980, that's when things really diverged further. But I think that also looking kind of below the surface, the urban, the correlation between density and Democratic voting in the Northeast and mainly the Northeast, but the kind of manufacturing oriented places was actually already quite strong in the, in the 30s and 40s.

And really the South, was making that relationship look weaker because the South was, had the exact opposite relationship. Well, and it really all sort of converged over time and that's like the nationalization story is that all of the different regions, the correlation between density and voting, converges on the same relationship everywhere.

>> Nicholas Jacobs: And there is no Charlotte, Charlotte that we know today in 1932. There is no Atlanta-

>> Jonathan Rodden: Right, yeah.

>> Nicholas Jacobs: Like today in 1932. And so some of this is just where the urbanization takes place. And as you brilliantly point out in your book, right, urbanization is a regional phenomenon in the early 20th century, late 19th century.

And then the places of urban growth are entirely different spots on the map in the late 20th century. And so it interacts with these regional effects as well.

>> Speaker 6: Do you think that there was any effect from cowboy movies that were just on people who're struggling to find a new identity?

I noticed, like my father, he was a cattle veterinarian, and there were many immigrants at the time in the valley, people came from all over. I mean, my grandmother came from Ireland, great-grandmother did. But there were people from many different cultures who worked in the farmlands. But I don't know, I think maybe there was some sort of changes with Hollywood.

And could you address that, thank you.

>> Nicholas Jacobs: Thank you so much for the question. And this is really where you want my co-author, Dan, to speak about it cuz he really rightfully saw, I think, what you see. Which is that if you just even think about the way rural is portrayed in pop culture today, I'm gonna get the quote, I'm gonna get the stat wrong, he counted them up.

And it's three digits, it's in the hundreds how many rural reality shows there have been in the last ten years, Duck Dynasty, Marry a Farmer, right? And what we do in the book is that's one bookend, right, rural reality show. What's the one he always talks about? The guy that rides his tractor into town to get the mail and can't resist shooting the speed limit sign as he's driving in.

And what we write about in the book, I think it's undeniably true, it doesn't lend itself to a nice bar graph. But you go from the world of Little House on the Prairie, right, where ruralism and pastoralism is idealized, to The Beverly Hillbillies to Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Now, this is not my genre, and again, Dan did the counting.

How many horror movies take place in an urban setting? I don't know, I mean, they're all in the woods. Now, where I do have data is, that's an interesting story and bunch of anecdotes, we did ask questions about this. We ask, and we ask people what stereotypes they feel are portrayed in media.

And this hardening of the rural portrayal is very visible in the minds of our rural respondents. They're more likely to tell us they feel misportrayed. They are more likely to tell us they feel portrayed in Hollywood as the yokel. So it's not just our observation being projected onto people.

I mean, people have told us that and reverse.

>> Jonathan Rodden: Over here?

>> Nicholas Jacobs: And there are exceptions, I get that, but I think the overwhelming flavor is of a certain type.

>> Speaker 7: Thank you for your talk. As you're talking about this kinda urban and rural divide and this idea of place-based identity kind of brought to mind another kind of more rural group within the United States, and that being Native Americans.

I was wondering what thoughts you have on kind of comparing these similar groups, obviously with different histories, but also that share a lot of similar characteristics, thank you.

>> Nicholas Jacobs: Thank you for the question, it's a really important question. As I mentioned at the very beginning of our exchange, we do not break out different groups in rural America cuz we find that a lot of these explanatory or predictive factors resonate across different experiences, I'll say, with one exception.

Which is Indigenous tribes, which make up a larger percent of the rural population than they do the national population. It's a very difficult population to study through my methodology. There's much more ethnographic and qualitative work that supports, I think, the premise of your question, that there is a similar resentment towards government, there's a similar history of bad policy.

But in no way do I think those are equivalent. And I do not fold that into a non-Indigenous rurality, even though, especially out in the West and in the Upper Midwest, the tribes make up an important part of a rural landscape, of the rural social economy, as it were.

It's a part of that rural diversity that I mentioned. So where I grew up in Virginia, it was not a part of our rural ways of being, and it's something I've become much more attentive to and sensitive towards. I mean, that's a long way of saying I think you're right.

And scholars that are much better versed in that subject than I, we've discussed and we found commonality. But the source material of that is of a different enough kind where I wouldn't loop it together.

>> Jonathan Rodden: But it's worth pointing out that this is perhaps the most overwhelmingly Democratic demographic in the country, even though it's rural and has rural identity and so forth.

I mean, that's a really important wrinkle, and I guess I wanted to ask. I know you've been doing it, you've got these rural over-samples that also are intentionally created to get Black over-samples in rural areas-

>> Nicholas Jacobs: And Latino.

>> Jonathan Rodden: And I'm just curious. So I always think of, again, think about my scatter plots.

When there's a density Democratic voting scatter plot, there are all these little outliers. And they're basically Native American reservations and the Black belt in the South. Could you say a little bit more about what you've learned about the ways in which rural Black voters are different from urban Black voters?

>> Jonathan Rodden: So First of all, are they different in terms of their partisanship or are they-

>> Nicholas Jacobs: Yes.

>> Jonathan Rodden: And whatever-

>> Nicholas Jacobs: Yes, I mean, so in the world, right, like Emerson says, we all contain multitudes, we all contain multiple identities. And you can be rural and Black and you can be rural and White, they're not always in conflict.

And what we know to be true nationwide and what we know to be true in rural areas and urban areas is that one of the most powerful motivating identities in American politics is one's identity as a Black person. And there are gaps in partisanship between rural and urban African Americans.

That gap was one of the most widened gaps in the last election. Both rural black women gravitated towards Trump in this last election, especially in a few key states, North Carolina and Alabama. Not sure. We just kind of got the data and we don't know if it's just a statistical aberration from polling, although I remember hearing quite a bit from some nervous folks organizing in North Carolina about what they were seeing on that.

Rural black men gravitated more towards Donald Trump in this last election than black men more generally. But I mean, you're talking differences of some single digits and you're still talking about vote share for rural black men in the mid-70s and rural black women in the high-80s. So it's leaning towards the Democratic candidate.

The more interesting thing is the one I sort of briefly alluded to with these over samples, which even with over samples on indigenous people and rural communities, still only gives us about 5%, which, you know, so it's a minority within a minority. That's incredibly difficult to get to through my methodology.

>> Jonathan Rodden: Really hard to.

>> Nicholas Jacobs: And here's the thing, when it's that difficult, like, I'm not saying I haven't looked at it, I think it's tremendously important. But I'm not gonna give you bad statistics, which is usually the course of action for rural breakouts like most polls. You see, you can get great polls with 1,200 Americans statistically valid within a couple of points.

You'd be hard pressed in that poll of 1,200 Americans to get 200 rural people, and your estimate would be widely over the map. The more interesting thing, I think within the rural south and the Black Belt in particular, is the fact that this sense of grievance and ruralness and rural identity is still very prevalent.

>> Jonathan Rodden: Does it prevent people from wanting to take surveys? Is it harder to get responses in rural places? In part because there's mistrust that is prevalent. Does that also extend to a researcher from Colby College who's trying to get people to.

>> Nicholas Jacobs: Well, yeah, maybe. If anything gives me a floor then, not a ceiling, cuz resentment is what's driving sort of some selection bias or opt in to my work.

But I mean, here's the little secret that for those of you familiar with surveys and polls, whenever I don't know if they call you all here in California cuz we know how you're gonna vote, but up in Maine, whenever Susan Collins is running, I get like three phone calls a day.

That's not how I do my work, to be honest. I pay people. It's amazing. You can get people to do stuff if you compensate them. So yeah, no, I don't know. But the substantive point is that a lot of that feeling is there. Those stories are there, they're cross-racial.

But when it comes to finally walking into the voting booth and picking a candidate, it's as true today as it was when the agrarian populists were trying to organize in the late 1800s. You cannot cross the color line.

>> Speaker 8: Hi, thank you so much for a wonderful talk.

It was very informative. I really resonate with your argument on the place based identity. I guess one question I have for you. Given your talk, it's very clear why Trump won. He felt he helped rural Americans feel seen and valued and their concerns were important. But many of his policies that he's putting forth aren't going to help rural Americans.

So I guess given your research, one question I have is how do we help the Democratic Party not only see rural Americans and value their concerns, but also put policies in place that are culturally aligned with their ways of thinking? Yeah, thank you.

>> Jonathan Rodden: Let's hope we get that question.

>> Nicholas Jacobs: Well, I never say I was trying to help a certain party. And let me be clear, I'm not trying to help a certain party. When I in the book write about and conclude, and Dan and I, we conclude exactly where you're pushing us to think about right now, what can be done.

We conclude emphatically that this is a problem for the Democratic Party to solve and have to respond to. Now we say that, and you can believe me or not, I have convinced myself of this. We say that not because we think that the Democratic Party has the best ideas or because the Democrats are the party of good and the Republicans are the party of evil.

We say that because our system, our political system is one that only functions with political competition. That's how elections produce accountable and responsive policy is when representatives running for office face real competition and historically, right? One of the reasons why the south remained one of the poorest regions of this country and of the world when put in global perspective throughout the 20th century century is because of one party dominance that maintained a set of policies and a regime that monopolized or was allowed to do that because it monopolized political power.

I care about rural communities, I'm very clear. I think it's obvious, that's my prior. I care about representative democracy. And you don't get representative democracy when one party rules.

>> Jonathan Rodden: One could say the same thing about cities as well, where one party rules and similar problems emerge.

>> Nicholas Jacobs: And if I understood cities at all, you could write the urban voter.

I think that's absolutely right. So what could a Democrat do? There are Democrats in the party that think about this question a lot. They think about it in terms of the language they use, not just at a policy, right? I think policies matter. I think recognizing policy failure matters.

I speak quite often to be with groups about, where in your politics is there room for recognition and then apology? Just something that's sort of odd to think about, but it is. It bestows a certain amount of dignity on some constituencies. So we think a lot about the language.

We can think about it structurally, where the Democratic Party invests resources. So the Democratic National Committee just got a new chair from Minnesota. He's not from rural Minnesota, but rural politics looms large in Minnesota. And one of the first elders actions he announced was to return to his strategy of mobilizing and investing in every jurisdiction, which was the strategy of Howard dean in the mid 2000s.

That was abandoned in 2008 with Rahm Emanuel and Barack Obama. You have countless numbers of counties that don't even have a local Democratic Party. Local Democratic Party does not show up to my county fair. And so there's an organizational component, and a resource Source component, I actually wrote something somewhat flattering about Joe Biden.

Joe Biden actually did something Barack Obama never did the November before November 2023. He stood in front of a barn and talked about consolidation in agricultural industries, particularly meatpacking plants. Wow, what a thought. Just to speak about an issue that would resonate with 20% of the American people, travel to a rural community.

Barack Obama did travel to technically one rural community during his presidency, Martha's Vineyard, just like I brought up at the start. You know, it's a big problem, it's a sticky problem. It's something that you're only gonna be able to make a dent on by chipping away at it on the margins.

And I think there's some marginal stuff Democrats can absolutely do.

>> Speaker 9: Hi, Thank for, thanks for a great presentation. So I'm from Norway and I thought I'd share a tiny anecdote. It really goes to your comment that it seems you allude to that rural communities preferences are kind of maximizing their community preferences.

And the founding fathers in Norway would resonate very much with that idea. In fact, when they founded the country, they were worried that there wouldn't be enough power in Oslo. So they thought this country won't be viable. The elites in Oslo and maybe Bergen would just give away the power back to Copenhagen or maybe to London.

Right, so what did they do? They deliberately founded the national idea in the rural areas with the farmers and so on. So that very much resonates with your idea and being a little bit involved in politics and policy making, I always kind of joke with the people that wants to move everything to Oslo to say, well, once you moved it to Oslo, why don't you move it to Copenhagen?

That's too rude because we have Denmark used to be our colonial overlords. If I say London, they won't get us angry. If I want to make them even more angry, I could say things like, look, I'd love to give you some power in Oslo, but you just want to give it to Brussels.

>> Nicholas Jacobs: Yeah.

>> Speaker 9: So now I didn't say anything about American politics, but if you can entertain the idea that the communities in these rural areas are simply right, that they are maximizing their utility in the community. And then maybe in the big cities they're more focused on other more narrow concerns or more prone to being affected by the elite.

I don't know if you think that's an interesting chain of thought. Thank you.

>> Nicholas Jacobs: So I think there are aspects of our constitutional political system that lead to all sorts of inequalities. The fact that we have single member districts that are territorial in nature lends itself itself to wasted votes gerrymandering minority rule in representative settings.

Right, and that's problematic. That's unfair. That breeds illegitimacy into our electoral systems. Right, this is what Professor Roden's work so brilliantly demonstrates. At the same time, I think there are aspects of our constitutional system that a dispute dispersing power that in remaining attentive to place and recognizing that people don't just make political decisions as a part of this abstract national body politic.

But within smaller communities has been important historically for keeping the nation together and I think breeds legitimacy into decisions. And that's a question question at the heart of, I think what RAI is thinking about and what Hoover's thinking about. Both of those can be true. So that's sort of what I'm thinking about in response to your question.

>> Jonathan Rodden: Tom, do you have some last words for us?

>> Speaker 1: Mostly my last words are words of gratitude to both Jonathan and Nicholas. Could we give them a round of applause, thank you.

>> Speaker 1: And I wanna thank you in particular, Nicholas, for spending a few days with us.

You got to meet not just students, but some of our scholars that are thinking about similar problems and challenges. Want to encourage everyone. One of the things that we may do in the fall, we've been having conversations with students. We're thinking we might bring some of the students together who are going out into rural places and have them on a panel to sort of share some of what their lessons were.