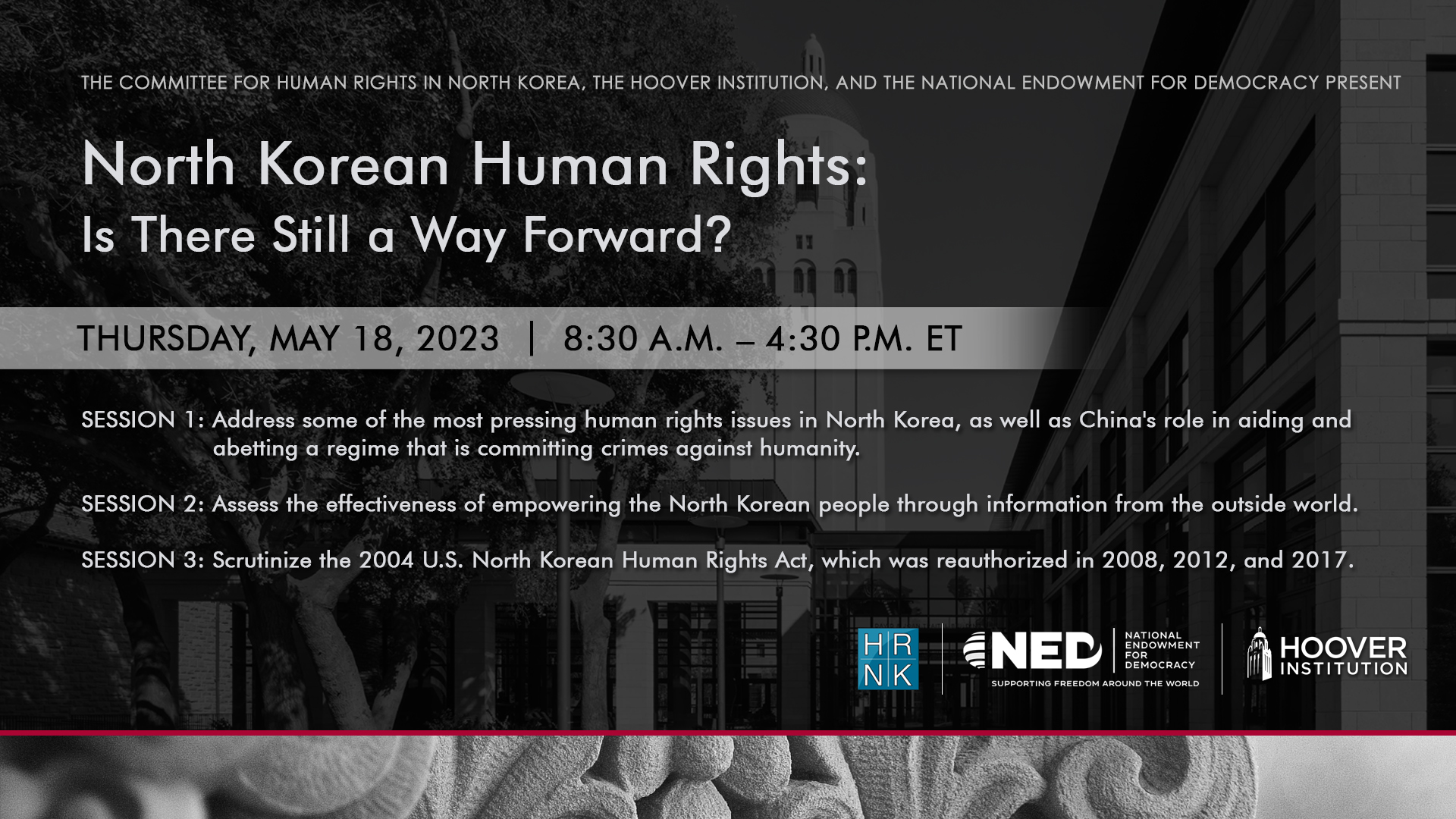

The Committee for Human Rights in North Korea (HRNK), the Hoover Institution, and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) have the pleasure to invite you to a full-day conference entitled "North Korean Human Rights: Is There Still a Way Forward?"

As North Korea continues to advance its nuclear and missile capabilities, this conference will examine the human rights situation in the country and explore how human rights issues may be elevated in future bilateral & multilateral interactions with Pyongyang.

This event will be held in-person. All in-person guests must provide proof of Covid-19 vaccination.

Session 1: Address some of the most pressing human rights issues in North Korea, as well as China's role in aiding and abetting a regime that is committing crimes against humanity.

Session 2: Assess the effectiveness of empowering the North Korean people through information from the outside world.

Session 3: Scrutinize the 2004 U.S. North Korean Human Rights Act, which was reauthorized in 2008, 2012, and 2017.

Closing Session: Explore the value of a "Human Rights up Front Approach" to North Korea policy.

>> Damon Wilson: Good morning, everyone. Welcome. And welcome to all of those who are here with us online as well. I'm Damon Wilson, president and CEO of the National Endowment for Democracy. And today we are gathered to discuss north korean human rights and to help forge a way forward. I want to start off just by thanking our good friend Larry Diamond, a veteran here at the endowment who is helping organize this as part of the Hoover Institution's commitment.

Greg Scarlettu, as well from the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea. Greg, thank you for being with us. Thank both of you for your leadership and organizing today's conference and discussion. I also want to give a shout out and thank Stephen Kong, who's with us. Stephen, welcome.

Welcome to Washington. It's good to have you here. Thank you for your support and your leadership in making this event impossible. But more importantly for the cause, I also want to acknowledge the Ned team and the other team members that have been putting work into making this possible.

Shout out to Abigail, in particular. Thank you for being running point on this. So we're here today because the world knows the Kim Jong un regime is one of the worst human rights abusers in the world. Its mere existence is a stain on the conscience of the international community, and yet international stakeholders have not done enough to take action to address it.

And we soon looking to next February, will commemorate ten years since the landmark UN Commission of inquiry report, which found irrefutable evidence of the systematic, widespread and grave violations of human rights in North Korea. So as the anniversary approaches, we need to be working, organizing. That's what today's about.

How do we think about where we've been over the past decade and what we do next to promote human rights in North Korea. Until recently, it feels like North Korean human rights issues have become a little bit more sidelined, further politicized. This has arguably, at times stalled the sense of momentum for many of the incredible NGO's that are continuing the critical work for advocating for increased awareness of human rights violations.

And accountability of the regime that are working to increase access to information, empowering defector voices to take leading roles in the movement. Support for human rights and the building blocks of a democratic future are top priority for the endowment. Indeed, during my first year as president of NED, I visited Seoul, the demilitarized zone, to visit with north korean escapees and those working to support their cause.

And when you spend time with many of these particularly young defectors, they help you understand that the regime is both ruthless and vulnerable. Ruthless in how it treats its own people, and vulnerable because of how it treats its own people. Our partners, our grantees, have been working tirelessly so that North Korean citizens can have more freedom to choose for themselves.

But as they work hard, we're feeling a sense of waning engagement on the issues from policymakers, international stakeholders. President Yoon's administration has helped to put some impetus into a focus on the importance of democracy and human rights to the korean people. But we need more action across the board.

Our partners are pushing back to put north korean human rights issues on the agenda and to escape from any politicized lens to keep the focus on people and their human rights. And they've been employing various approaches to elevate human rights issues and increase awareness. The transitional Justice Working group's recent report on human rights violations near nuclear testing sites show that there's a tie, a link between nuclear security and human rights issues.

We're going to hear from Ethan Chin, who'll be speaking today. The Citizens alliance for North Korean Human Rights has also produced an important report on coal production, linking the supply chain and financing of the economy with forced labor. Bridge International has worked with young defectors and South Koreans to employ an entrepreneurship and innovation model that derives creative solutions to the human rights challenges in North Korea.

And these are only a few examples. You know, many more of the courage, the creativity of Ned's partners working to ensure a better future of the north korean people. Indeed, it's remarkable when you see North Koreans who have just a bit of time and freedom, what they produce, what they generate, what they drive forward.

It speaks to the power of liberty. And in this work, we want more partners. We want more who are part of this cause. We welcome South Korea's investment in supporting human rights on the Korean peninsula. We welcome those who care about freedom and democracy around the world, rallying to the cause of the people of North Korea.

Because one thing's certain, that human rights permeates so many aspects of both policy and people's daily lives, from their personal security, to the big nuclear issues, to the economy, to society. The deprivations of the people of the North Korea, the deprivations they suffer, they are a scourge to humanity.

So for this reason, human rights should be at the forefront of addressing the North Korea challenge. It should be our priority to stand in solidarity with North Korean citizens so that they have the agency to help choose their own future. And that's why we're really pleased to welcome our institutions that are helping to run and organize this today.

It's brought together some of the leading experts on North Korea to address the top order challenges that include empowering the North Korean people through information from the outside world. China's role as a dictatorial patron, if you will, and why we should purposely elevate human rights in the North Korean context.

We're going to look to you, the experts who are with us, to help forge that way ahead. What is the next step of this agenda? Addressing the grievous human rights situation in North Korea is a key pathway towards more freedom and openness for the North Korean people. It's an honor to have you with us.

Thank you. And with that, I want to invite Larry Diamond to the podium. Welcome to the endowment, everyone. Thank you.

>> Larry Diamond: Well, thank you, Damon, for those beautiful opening remarks. Thank you to the National Endowment for Democracy once again for being such a wonderful partner and host. And most of all, to Chris Walker, the vice president for studies here and the international forum.

And of course, a hearty thanks to Greg Scarletoo and the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea, who have been laboring so nobly and eloquently on behalf of this vital issue. It's just been great getting to know you, Greg, and partnering on this conference. I also want to thank Steve Kong, whose initiative helped press us to do this and who's been a very devoted supporter of this cause of human rights in North Korea.

As Damon has already said, certainly one of the most important and overwhelming human rights emergencies in the world. Now, that leads to my second point, which is that it's been a, what you know by now, something like 75 year emergency. I spent some time on the airplane reading the annual State Department report on human rights in North Korea, and there were two things that struck me about this.

This report. One is, I know comparisons to the Holocaust are dangerous, ill advised, and almost always wrong. But there is a comparison in this sense, it's so systematic, so relentless, so overwhelming, and so depraved that it leads you to a very dark sense of what human beings are capable of in terms of how they treat their fellow human beings.

There really are few systems, I think, in the history of the world that have developed such systematic forms of degradation and human enslavement. And the second thing that struck me about the report is it wasn't much different from what you could have read two or three decades ago or more.

The reports only started being produced in the Carter administration. So that goes back, I guess, about 45 years. That leads to two more points I want to make which I think you will hear in this conference throughout the day. One is that we keep being told over and over again when we raise this issue, we can't really talk about human rights.

North Korea has choose your number 40, 60, 200 nuclear weapons. That's what we got to focus on, negotiating down and hopefully away their nuclear weapons. But there's an intimate link, which I think many of our presenters have very perceptively and persuasively identified, between the paranoia of the regime.

The insecurity of the regime that has led it to amass all these nuclear weapons, and the same paranoia and insecurity that has created in an entire country, one giant prison camp. And these analysts, who you will hear today over the course of the day, I think, make a compelling case that even if you mainly care about the nuclear program.

You ought to care about human rights because unless we change the nature of the regime internally, we won't change the nature of the regime externally. And then secondly, to preview some of the arguments you will hear if you believe that the regime must change and that there's something we can do to facilitate and encourage the people of North Korea to somehow bring about change.

Information flows are absolutely critical. This has been the most isolated country in the world. It's beginning to change a little bit. There's much more that we can do to help facilitate and expedite that change, with creative uses of technology playing an extremely important role. I'll just say one last thing on a personal note.

About a little over a quarter century ago, with the assistance of an extraordinary man and organization, the Reverend Benjamin Yoon and his Citizens Alliance in South Korea. The Citizens Alliance for Human Rights in North Korea, I met and had a chance to interview for the Journal of Democracy some of these defectors, some of the first few that made it to South Korea.

It's a searing and unforgettable experience, but it's also an extremely inspiring experience to see how people can survive, endure, and prevail in the face of these really horrific circumstances. And, of course, those will be the people who changed North Korea. So with that, Greg, I pass it over to you.

>> Greg: Thank you very much, Damon and Larry, it has been a true privilege to partner with a National Endowment for Democracy and the Hoover Institution and President Damon Wilson, Vice President Christopher Walker, Doctor Larry Diamond, a pleasure working with you and your teams. Steve Kang, our board member, thank you very much for your vision and your staunch support for so many projects that are ongoing.

Let me also take the opportunity to thank our co-chair emeritus, Roberta Cohen, for joining the panels and also joining conference today, David Maxwell. Later, we will be joined by Ambassador Robert King and Ambassador Robert Joseph as well. Ambassador Robert Joseph has led a project proposing a paradigm shift.

Why a paradigm shift? Well, this point will be made over and over again throughout the day. Thomas Kuhn, philosopher of science, came up with the idea of the paradigm shift. We go through these long paradigms that fit the circumstances, and then the paradigm no longer fits the circumstances.

It has been more than 30 years since human rights has been outcompeted by very important issues. Nuclear weapons, ballistic missiles. North Korea has very recently tested a solid fuel missile, and Dave, Max and others will explain the importance of that development. Today, according to the Rand Corporation, North Korea will be in possession of more than 200 nuclear weapons by the year 2027.

That's an arsenal comparable to the nuclear arsenal of the UK and France. We do need this paradigm shift, and we will be discussing this today. Human rights must be placed up front and center in order to secure its survival. The Kim regime produces its nuclear weapons, its ballistic missiles, has to keep its core elites happy through access to luxury goods and hard currency from the outside world, despite international sanctions, despite US, UN, EU, Japanese, and other sanctions.

It's a very simple story. In order to procure the hard currency it needs to maintain itself in power, the Kim family regime oppresses and exploits its own people at home and abroad. And that is the very basic connection between human rights and North Korea's ballistic and missile programs that threaten regional peace and security.

Let me take this opportunity to credit NED for the great work NED has done supporting organizations that send information into North Korea. Dave Maxwell, this is time to bring up the three stories included in our report. It is very important to tell the people of North Korea three stories.

Number one, the story of the corruption of their own leadership, in particular, the Kim family regime and their supreme leader. Number two, the story of the outside world, in particular, the story of free, prosperous, democratic South Korea. Republic of Korea. By the way, none of us are perfect democracies do not claim to be perfect democracies.

Acknowledge their issues, correct those issues, and move on. The only ones claiming to be perfect democracies are the North Koreans, the Venezuelans, the Cubans, the Russians, the Belarusians, and the others. We know who they are. And of course, the third story that is the story of the human rights of the people of North Korea.

North Korea joined the United nations in 1991. It acceded to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, the Women's Convention, the Children's Convention. The Convention on the Rights of People, Disabilities, and yet each and every conceivable human right is violated in North Korea.

This is a regime that commits crimes against humanity, in particular at his detention facilities, at his prison camps. This also goes against North Korea's own constitution, believe it or not, as all of you know. There are wonderful human rights included in the North Korean constitution, such as freedom of religion, freedom of speech, expression.

None of these rights are observed. So this is what this conference is about. We need a paradigm shift. Will we be successful? We don't know, but we will give it our absolute best, because nothing else has worked for more than 30 years. And the only way to do this is to do it together with Ned, with the Hoover institution, with Ned's grantees, and with all of our other colleagues.

Many of you are in the audience today. I look forward to a fantastic day and a great conference. Thank you very much. And being the third introductory speaker, I also have the privilege of inviting the first panel to join us. And of course, Olivia Enos will introduce the speakers.

Olivia Enos, Roberta Cohen, Tara O, Ethan Hisok Shin, please. And of course, Olivia will introduce the speakers. And somebody has to introduce the moderator. I get that privilege. Olivia Enos is the Washington Director for the Committee for Freedom in Hong Kong. Prior to her current position, she was a policy analyst in the Asian Studies Center at the Heritage Foundation, where she wrote about international human rights issues.

Including human trafficking, transnational crime, religious freedom, democratic freedoms in China, in Hong Kong, in Burma, and other parts of Asia. She has been a contributor to Forbes since 2016. She received her BA from Patrick Henry College and her MA in Asian studies from Georgetown University. Olivia, Godspeed.

>> Oliva Enos: Well, thank you so much for having me here today, and thank you to all of you for joining us here today.

In preparation for this panel, I spent some time thinking about why policymakers favor a security-based approach as opposed to a human rights and values-based approach. And I came up with three reasons. First, the argument is familiar. It takes a concept that any person who took Intro to IR would be familiar with, realism.

It's this idea that all actors are driven by power, both its acquisition and its preservation. In the North Korean context, the argument goes something like this. The Kim regime has its weapons programs, specifically its nuclear weapons, as well as its missile programs, and it has those programs in order to maintain its grip on power.

Simple enough. The argument also has the benefit, secondly, of being true. The Kim regime does think that it needs nuclear weapons in order to stave off so-called US aggression in order to maintain power. And third, it's connected to US interests to advance and counter North Korea's security threat.

We don't want North Korea to attack the US and our allies, so it's in us interests to thwart North Korea's nuclear ambitions. I think all of this is simple enough. It's easily understandable. But what if I told you that the same arguments that justify countering North Korea's security threat are actually present when it comes to countering the threat that the regime poses to human rights, specifically against its own citizens?

To paraphrase current Deputy Assistant Secretary Jung Pak in her book Becoming Kim Jong Un, human rights and the nuclear program are two sides of the same coin to the Kim regime. And to best understand their similarities, I think it's important to break down these arguments in the human rights context.

So first, just like in the national security context, the argument is simple. It's rooted in realism. The Kim regime believes that it must violate the rights of its people in order to maintain power, same motivations. Second, the argument has the benefit of being true. The Kim regime needs an acquiescent people, or believes it needs an acquiescent people to continue its weapons development and to continue with its belligerent foreign policy.

But how does it go about securing an acquiescent population? Well, first, by threatening its people through policies like sending three generations of a family to political prison camps, carrying out public executions. Carrying out purges that even threaten senior leadership in order to maintain the silence of the people and any who would oppose the regime's ends.

Second, it does so by using North Korean forced laborers, principally for profit and maybe even for weapons development, as Greg alluded to in his opening remarks. And third, by using its people to advance its weapons program by allegedly testing chemical and biological weapons on some of the most vulnerable people in its population.

Those who are disabled, Kotjebi orphaned children, and those who are in the prison camps. Third, just as with the first argument, it's connected to US interests. It is in US interests to see freedom for the North Korean people, in part because of its connectedness to the nuclear program.

But also because both Republican and Democrat administrations have said that they promote a free and open Indo-Pacific strategy. In the report that Greg mentioned in the opening remarks, we released a national strategy for countering North Korea. This was spearheaded by Ambassador Bob Joseph, and I was tasked with outlining the myths and facts that are present in US policy toward North Korea.

One of the biggest myths by far is the notion that making progress on our security concerns with North Korea is antithetical to advancing human rights. I would argue that it's quite the opposite. Without progress on rights, without a prioritization of the preservation of rights, it's difficult to make headway on security at all.

So we are tasked today at this event in this panel with answering the question, North Korean human rights, is there a way forward? Of course there is. And a more cohesive strategy will place a premium on ameliorating the threat the regime poses to human rights in tandem with.

With addressing the security threat. We have some wonderful folks who are here today to shed light on the human rights violations that we seek to address. It is my hope that our audience will walk away from this panel with a better idea of the scope and the scale of the North Korean human rights challenge, as well as step away better equipped with knowledge on getting US policy towards North Korea right.

So without further ado, I would like to introduce my panelists to kickstart what will no doubt be a fruitful discussion. So first up, we will have Roberta Cohen. Roberta Cohen is co-chair emeritus of the Committee for Human Rights in North Korea. She's had an illustrious career spanning the United Nations, the State Department, thinktanks, specifically at the Brookings Institution, NGOs, and academia.

Where she's been a specialist in human rights, humanitarian and displaced persons, as well as refugee issues, which she will cover here today. Next, we will hear from Dr. Ethan Hee-Seok Shin. Dr. Shin teaches international law at the Catholic University of Korea. He's a researcher at the Institute for Legal Studies at Yonsei University and a legal analyst for Transitional Justice Working Group, a Seoul-based human rights documentation NGO.

His area of interests include transitional justice and human rights issues in Asia-Pacific. He holds a PhD in law from Yonsei, an LLM degree from Harvard Law School, and a BA in economics from Yonsei University. And last, we will hear from Dr. Tara O. Dr. O is the author of The Collapse of North Korea: Challenges, Planning and Geopolitics of Unification.

She's a fellow at the East Asia Research Center and the Institute for Korean-American Studies, as well as an adjunct fellow at the Hudson Institute. Dr. O is a member of the Academic Council of the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation. She has also served as lieutenant colonel, she's now retired, where she worked on national security, intelligence, alliances, and political military issues at the Pentagon, the United Nations Command and Combined Forces Command, US Forces Korea, and US European Command.

She holds her BA from the University of California at Davis, an MPA from Princeton University, and a PhD from the University of Texas at Austin. I think you will all agree we have an illustrious panel to learn from, but we'll kick it off with comments from Roberta.

>> Roberta Cohen: Good morning, everyone, and thank you-

>> Oliva Enos: I think you need to turn on your mic.

>> Roberta Cohen: Push, okay. Good morning, everyone, and thank you to NED, the Hoover Institution, and of course, HRNK for hosting this program. Let me begin. And thank you, Olivia. Let me begin by recalling that ten years ago, the United Nations Commission of Inquiry into Human Rights in the DPRK found that of the 300 witnesses it had interviewed, more than 100 had directly experienced forced repatriation from China.

And as a result, had been subjected to cruel and inhuman punishment in North Korea. This influenced the COI to include the role of China in its mandate when investigating whether crimes against humanity were being committed in North Korea. China's collusion with North Korea is one of the prominent features of the North Korean refugee program.

China not only forces back North Koreans who enter its country without authorization, but shares information with North Korea about those who escaped, allows North Korean security agents to monitor, hunt down. And even abduct North Koreans on Chinese soil, is reported to help identify those who are Christian, and requires its own citizens to turn in North Koreans.

The COI chair, Michael Kirby, warned China that its officials could be found complicit in aiding and abetting crimes against humanity in any future trial. The starting point of the crimes, of course, is that North Korea has made the right to leave a country and the right to seek asylum criminal offenses.

Anyone who tries to leave without permission or is turned back is subject to detention. And it can be up to five years, which includes beatings, degrading searches, torture in many cases, denial of adequate food, forced labor, gender-based violence, forced abortion, and possible transfer to long-term prisons. There are even cases of executions.

The most severe punishment is meted out to those who try to reach South Korea, or were in contact with South Koreans, or were helped by Christian churches in China, or professed to being Christian. North Korea also punishes the family members of those who try to reach South Korea.

Let's look at an actual case. As we speak, there are hundreds of North Koreans being held in detention in China, some of whom tried to reach South Korea. Any day now, they could be forcibly returned. Because North Korea's border is still closed because of the pandemic, China has waited to send them back.

South Korea is ready, of course, to take them, regarding them as its citizens. But China is reluctant to give safe passage, primarily fearing that if they let some go, that greater numbers of North Koreans will try to depart, and this could destabilize the Kim regime. China did, however, allow safe passage for a family of four last year, I am told, but for the most part, chooses to comply with the agreements it has with North Korea that provide for the return of any citizen who crosses the border illegally.

These arrangements contradict North Korea's and China's international obligations as set forth in the Refugee Convention and the Protocol, which they both signed, and also the Torture Convention, which China signed. The international agreements forbid the turning back of refugees where their life and freedom would be threatened, and the Torture Convention forbids the return of anyone to torture.

In addition to those in detention, China also forcibly repatriates undocumented North Koreans residing or working in China, many of them women who may have been trafficked or in marriages. China doesn't Recognize if deported, the mothers are then separated from their children and their Chinese husbands. Despite all the forced returns, I would say about estimates of tens of thousands over the past 20 years.

More than 33,000 North Koreans managed to reach South Korea through China and Southeast Asia over that period. But the closure of North Korea's border following the pandemic, combined with shoot to kill orders, has made the number plummet. Only 67 reached South Korea in 2022, whereas before the pandemic there were over 1000 a year.

What role can the United Nations High Commissioner for refugees to be of assistance? During the great famine in the 1990s, UNHCR staff was able to interview North Koreans at the border, and they began to classify some as refugees. China then barred UNHCR from access to the border. That was 1999, and in 2008 it barred North Koreans from going to the UNHCR office in Beijing, which had been helping small groups of North Koreans to depart.

China put forward the argument, from which it has not deviated, that all North Koreans coming over the border are economic migrants who should be returned. When UNHCR staff suggested alternatives, China rejected them, for example, the term persons of concern meriting humanitarian protection, or the UNHCR term refugee surplus.

Which means that no matter why a person left their country, they could be deemed refugees if they have a well founded fear of persecution upon return. Nonetheless, on an exceptional basis, China has allowed safe passage for certain defectors from North Korea, especially those with ties to China, and also others, although there's no criteria, including those in 2012, who were hiding in foreign embassies in Beijing.

Some seven to eight years ago, without any access to North Koreans, UNHCR began to move away and stop making any sort of public statements about the north korean refugee situation. Around the same time, China's growing political and economic influence internationally was accompanied by pledges of hundreds of millions of dollars for development programs in refugee hosting countries.

Some of this money, I understand, to go through UNHCR. In 2017, China's president promised a billion dollars from its Belt and Road Initiative to international organizations for refugee related projects. When the High Commissioner for Refugees visited China in 2017, that same year, he praised UNHCR's relationship with China and expressed the hope that China would invest some of its Belt and Road initiative in countries hosting large numbers of refugees.

To conclude, this small and cruel refugee situation involving North Koreans needs a focal point within the UN system and an overall UN wide strategy. At present, the dominant voice at the UN on China's forced repatriations is the office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. It is no longer UNHCR.

However, this issue is more than a human rights issue. It's also a refugee issue, no matter the mantra or party line that China has cooked up. It's also a humanitarian issue and a political issue. The best way to move forward is to have a unified UN approach under a policy that actually Ban Ki-moon, the previous secretary general, introduced, which calls on the entire UN system to be engaged when there are grave human rights violations.

At the same time, a diplomatic solution should be sought. The secretary general, and this is Antonio Guterres, who used to be the high commissioner for refugees. When they did speak out about the refugee situation, as secretary general, he called on the international community to take steps to ensure that North Koreans who crossed international borders irregularly are protected and not repatriated.

A contact group of states needs to be created to include states affected by the refugee problem, states prepared to house North Koreans temporarily while their future is determined, and states in a position to effectively raise the issue with China. Emphasis could be on burden sharing and humanitarian concerns.

After all, North Koreans shouldn't be sent back to a country where there is insufficient food for much of the population. Detention facilities, moreover, breed health problems and should be closed. If China wants to become a player in refugee and humanitarian and development issues, it must demonstrate some compliance with international refugee, human rights and humanitarian norms.

Thank you.

>> Oliva Enos: Thank you, Roberta. I really appreciate that. I think I learned something new. I didn't realize that UNHCR staff used to be able to actually interview people at the border. That was really.

>> Roberta Cohen: It's not known.

>> Oliva Enos: It's really helpful to know that. And obviously would be great to be able to do that again.

Tara, would you like to speak next?

>> Tara O: Sure, yeah.

>> Oliva Enos: Thank you.

>> Tara O: Well, thank you, Olivia. And good morning, everyone. I'd like to thank the NeD, HrnK and the Hoover Institution for hosting this forum and for inviting me today. The topic of my talk will be, it's actually a question, is South Korea a safe haven for defectors from North Korea?

And I'm gonna look at the, it'll be a review of the Moon administration and what happened during that time. And to state it very clearly, this five years, and that is from May 2017 to May 2022 of the Moon Jae administration. Yeah. Okay, so quickly, the topic is South Korea.

Is South Korea still a haven for the defectors from North Korea? And I'm going to review the five years of the Moon Jae in administration, which was from May 2017 to May 2022. And that five years, it was a terrifying time for the defectors and not just for them, but also for South Koreans as well.

And I will explain, and I will start with a couple of quotes from the defectors. So one defector, his name is Hao Kuan il, and he is the head of the committee for Democratization of North Korea. What he said was, South Korea is no longer a haven for defectors from North Korea, the current administration.

And when he said this, it was under Moon Jae in administration. So the current administration is pro North Korea, and thus, it is very hostile to the defectors from North Korea. Kim Sang min, he is another defector. He has a free north Korean radio. He said that the Moon administration is working with the Kim regime and is suppressing all of the north Korean defector organizations activities in South Korea.

And these are documented in the congressional testimony by doctor Suzanne Schulte, who did this in April 2021. So let's review some of the events that occurred. Anti leaflet law. And I'm sure many of you have heard of this. In June 2020, Kim yo jong, so that's Kim Jong un's sister.

Basically she complained about the leaflet sending by the north korean defector groups in South Korea. That was June 4 in the morning. By that afternoon, South Korea's Ministry of education made an announcement saying that they will ban the leaflet sending. It was that quick. And that was soon followed by the National Assemblyman, the lawmaker, Kim Hong Ged.

He is of the Democratic Party of Korea. And in Korea, it's called Taobura Minju party. So he is actually the son of Kim Dae jong, former president. He quickly introduced a bill to ban leaflet sending, and that was eventually passed later that year. One more person that I'd like to highlight is Lee Jae Myung.

He was the governor of Gyeonggi province at that time. And what he said was, I will arrest on the spot those who are distributing leaflets to North Korea as criminals. He also said that I will preemptively block all possible ways. And he sent police to harass some of the defectors and defector groups, sending leaflets.

Just in case you may not have heard of him, he ran for president in the last presidential election and lost by only 0.7%. And he is now the head of the Democratic Party of Korea party. And when they passed this law, they basically criminalized it with three years of imprisonment or ₩30 million fine, which is about $28,000.

So this was one of 15 laws that that party prioritized at that time. There were numerous other laws that suppressed freedom, including the May 18 special act. And today is May 18. It's about Gwangju. And basically, if you say anything other than that it was a democracy movement, then you can go to jail for five years.

So, in fact, Guangzhou city is investigated by 11 young people. One of them for example, on his YouTube channel, he said he used the term Gwangju uprising instead of Gwangju democracy movement. So they are investigating him for violating the law. So with something like this and with the party passing all kinds of laws like this, this is very unnerving, and it really makes the defective community nervous, as well as many South Koreans.

I have five other events that I'd like to talk about so quickly. Moving on, there are, and you may have heard of this, the two fishermen that were sent back to North Korea through the DMZ. And you may have seen the photos where they resisted. They collapsed and didn't wanna go, but they were sent forcibly, and that was November 7, 2019.

The Moon administration justified sending them back to North Korea, saying that they murdered 16 people. But there's no evidence for this. In fact, the National Intelligence Service, which is like the CIA in Korea, some of the lower officials, they actually were going to start an investigation. But SEO hoon, who moon appointed as a director of NIS, he arbitrarily canceled it.

So they never had an investigation. So how do they know what happened? They basically quickly sent them back. And they also said that those defectors said, well, they claimed, the Moon administration claimed that. They said even if they die, they want to go back to North Korea. And it turned out to be not true, not only because the way they resisted, but they actually made statements saying that they wanted defect.

But those statements didn't come out until after the moon administration ended. So these are the things that happened. But they were not the only defectors from North Korea who were sent back. There were three north korean defectors that were sent back in December 2018. So it was prior, and I don't think this really made the news except for this other portion of it and so I need to back up a little bit and give you a background.

You may recall that the Japanese defense minister said he strongly protests South Korea's south korean navy destroyer locking its fire control radar on japanese patrol aircraft over the sea of Japan, what Koreans call ec. So it's related to this. First of all, locking a fire control radar on an aircraft.

You don't do that. It's extremely threatening. It's something you don't do unless you're ready to fire a missile and destroy a target. So it's that threatening. So this patrol aircraft had to leave the area and fly to safety because the moon administration did not want them to monitor what was going on below.

So what was below? A boat with defectors. In fact, the japanese officials found them first because they were actually closer to Japan. They were going towards Japan. And they confirmed that there were four North Koreans. One was dead because he was shot as he was escaping North Korea, and the other three were alive.q But Moon Jaein rushed.

A navy destroyer over there to bring them back, have them turn around, bring them back to South Korea, only to send them back to North Korea three days later. And people think that they were killed by the Ministry of State Security, and there is a lot more background to this, maybe I can cover that during Q and A.

And then that's, again, not the only other, talk about two boats, two defectors, or two events of defectors coming by boats who were returned. But according to Kim Tae-hee, another defector, he said that about 250 boats carrying defectors from North Korea were sent back in 2018 alone. So all of these really need to be investigated.

So, in addition to sending these defectors back, when these people from North Korea who escaped to China, when they request help during Moon Jae in administration, there was no help from the government. Several years ago, a South Korean POW who was held in North Korea escaped North Korea, he went to China, and he asked the South Korean government for help, but the Moon government did not help.

So he was returned to North Korea. And we know that he has the lowest hongbin, lowest echelon in that society, he left North Korea, and he also tried to go to South Korea, all these are considered crimes. So, he was one of 74,000 POWs who were not returned after the armistice signing.

About 81 South Korean POWs actually escaped North Korea since then. And in 2021, a group that helps defector or POW escapees from North Korea, they estimated that there are still about 170 POWs left in North Korea. Of course, this POW who was in China, he wasn't the only one that the Moon administration didn't help.

There was also in January 2020, a group of defectors escaped North Korea, went to China, and they stayed low, but eventually they were caught when they tried to escape or try to leave for South Korea. That was in September. And so they asked for help, this is a group of a family of three, and they were Christians, and as Roberta mentioned, Christians get more severe treatment, including execution, if they're returned to North Korea.

So, if we had them, this group also included two women who were human trafficked, and again, they were not helped, the Moon administration didn't do anything. So there are many more instances like this which made the defectors living in South Korea very nervous and afraid. So now there's a new administration in South Korea.

So, we can all relax or not? I would say no because the power base that put Moon Jae-in in power, they're still going very strong, they're very well organized, very well funded. His party is still the largest party in South Korea. And the polls, even if some of the methodology is questioned, the polls consistently show that this party receives about 20 to, actually, I'm sorry, 30% to 40% support.

So that's very, very unsettling. And then, of course, there are a lot of organizations, including the KCTU is a Korean labor organization, which is very, very pro North Korea, and they're always demonstrating to have the US troops leave South Korea. And they're actually being investigated by the NIS, because some of those members at the top are spying for North Korea and taking orders from North Korea and doing things to support South Korea.

So these things are very sort of rampant in South Korea, and a lot of South Koreans are now waking up to all this. So, we have to remember that last presidential election, President Yoon won by only 0.7%. So we have to be mindful of what's going on in South Korea and pay attention, because if South Korea is not safe for these defectors from North Korea to go to, where else are they gonna go?

Thank you.

>> Oliva Enos: Thank you, Tara. It's really helpful to get that context into, sort of the life and livelihood of defectors in South Korea. So thank you for giving us that insight. Ethan, over to you.

>> Ethan Hee-Seok Shin: Thank you.

>> Oliva Enos: And don't forget, yeah.

>> Ethan Hee-Seok Shin: All right, I think it's on.

I actually prepared PowerPoint presentation, I'm not sure. Okay, never mind, sorry. So what I, well, first of all, I'd like to thank Ned and also HN K and the Hoover Institution for organizing today's event, and also for our panelists and participants for coming here and showing your interest in North Koreans issues.

And what I plan to discuss today is to kind of talk about what the kind of work that my NGO, TJWG, has been doing over the years and how we find all these China related dimensions to many of the work that we have been doing. So our organization, transitional justice working group, was first founded in 2014, so it's almost ten years now.

And our two main projects, flagship projects have been one concerning the mapping of the public executions in North Korea using the Google Earth solution. And also the other project concerned the creation of an online database of the abductions and enforced disappearances committed by the North Korean regime. And so, with respect to the public executions and also other forms of state killings committed in North Korea, we ask the main source of information, obviously, has been the over 33,000 defectors in South Korea.

And in addition to the classical way of kind of asking them the questions and jotting down the answers. We also asked them to pinpoint the locations of the public executions that they witnessed and the secret barrier sites where the bodies were taken after these executions. And we basically tried to visualize the executions taking place in North Korea.

With respect to the enforcer's appearances online database, we again rely on open source information to basically try to record the very broad range of disappearances committed by the North Korean regime. And when I say broad, in time wise, it goes back to the late 1940s, to the very creation of the North Korean state.

That's when they started to. They were already abducting South Korean citizens both during, before the Korean War. And as Tara just explained, over 50,000 people were not returned after the 1953 Armistice Agreement. And then all the abductions that took place after the 1953 Armistice Agreement. And obviously the biggest victim class being the North Korean people themselves, God knows hundreds of thousands who have been taken to the political prison camps and probably most likely perished in these prison colonies.

And more recently, we have published a report on the radiation exposure from the Punggyeri nuclear test site in North Korea. This is something that initially has been covered by the news outlets, and also, we've heard a lot of anecdotes from the defectors from that area in the past.

But we wanted to kind of put together all the evidence and open source information that were out there to kind of put together a very coherent picture of the risk of radioactive contamination through the groundwater sources. And we were planning to do this under the previous administration, but we really couldn't find necessary information at the time.

So we basically waited until last year, after the change of government took place in so to collect more information, both from the government sources and also from the defectors. And we were able to present our report this February, which led the South Korean government announcing that it would resume the radiation testing for the over 800 North Korean defectors from the Kyochu county and the surrounding areas.

So in all these issues, one common theme that I found was China. So, as Roberta mentioned earlier, with respect to many of the people who are disappeared in the political prison camps, they actually, many of them are defector people who have fled North Korea to China and were returned by the Chinese authorities back to North Korea.

And basically, the North Korean government tried to classify. They repatriate North Koreans into one category, basically like people who went to China for economic, primarily for economic reasons, without necessarily trying to defect to South Korea or contacting South Korean missionaries in China. So those people, that group will be treated relatively lightly.

I'm not saying that they get off hook. They actually sent to labor prison campsite for mountaintop years, but they are treated somewhat lightly, more likely. Whereas the North Korean defectors who are presumed to have tried to defect to South Korea is the ones who are captured, for example, in Sichuan near the Chinese border areas.

That's pretty tell sign of them trying to leave the country and try to make a found a way to South Korea or countries. Those people would be considered political criminals and more likely to be sent to the prison colonies run by the Ministry of State Security. So again, there's a clear role of China in the enforced disappearances concerning the defectors that are sent back to North Korea.

And also many of them face public executions for the crime of trying to free their countries. And also many of them end up getting killed in the very brutal torture and treatment needed by the North Korean authorities when they are sent back from China. So we have identified these clear role of China in many of these violations.

And so one of the things that we wanted to do was, as Roberta mentioned, we tried to utilize the UN human rights mechanism to basically hold China account for its role, its complicity in these violations. And just last Friday CEDAW, the main UN treaty body for women's human rights had this periodic review about China's human rights record in the implementation of the CEDAW convention.

And for the first time, the North Korean human rights NGO's made four submissions to the CEDAW and also made an oral intervention prior to the actual review last Friday. And basically when the actual hearing took place last Friday, a couple of the members of tuxedo raise these issues to the Chinese delegation.

And we are hoping that the concluding observations, which will be adopted in two, three weeks time, will actually for the first time mention China's violation of the CEDAW Convention by facilitating trafficking and other human rights violations suffered by the North Korean women and their children in China. So we want, so again, we don't know if, how China will react to all these recommendations from CEDAW, but at least we first of all want to test how China will react to this kind of UN intervention.

And also, secondly, if they decide not to change their policies or course of action, then at least they will pay this kind of reputational cost at the UN level. So we are planning to bring more submissions for other treaty bodies when they review China's human rights record, because China is a treaty party to the torture convention, the civil and political rights covenant, and kind of social and cultural rights covenant as well.

So we do want to raise these issues in other UN forums as well. And also China's universal PR review EPR is coming up early next year, and actually the deadline for the NGO submissions is coming out in about two months time. So we also again, want to highlight China's involvement, complicity in these North Korean related human rights violations so that they will actually have to face the consequences at the international stage.

And finally, with respect to the Punggyri nuclear test, the radiation report we recently published, we recently translated our report, which was released in February in English and Korean into Chinese, and we haven't released it yet. But our hope is that when we release this Chinese version of the report, it will be read by hopefully many ordinary Chinese people who might actually feel more threatened by this kind of radiation exposure from the North Korean nuclear test site, more so than the.

Central government. And after all, China is the country located closest to the Punggye-ri test site in North Korea. So that's, again, like, we are hoping to actually put pressure on the chinese government from this kind of from below, from their own people as well. So yes, these were some of the observations and the kind of efforts that we're trying to make to actually hold China accountable for their role in the North Korean human rights tragedy.

And I'd be happy to discuss more in detail about this kind of work in the Q and A session. Thank you.

>> Oliva Enos: Thank you so much, Evan. I think it was really helpful to hear about the role of China in kind of perpetuating the human rights violations that North Koreans are facing.

So I'm gonna take moderator's prerogative, and I'm gonna ask the first question, but only so that you all in the audience can be preparing your questions. When you ask a question, please identify your name, any affiliation, and please ask a question. But I'm gonna ask you all a question first.

You each touched on various aspects of North Koreans and the human rights violations that they experienced. If there was one thing that the international community could do that the UN administration in South Korea could do or that the Biden administration could do today that you think would have the greatest impact in helping to ameliorate some of the human rights challenges that they're facing, what would that be and why?

Ethan, I'll start with you. We'll go in reverse order.

>> Ethan Hee-Seok Shin: Okay, thank you. I think that's a very important question. So I think it's very easy to assume that when it comes to North Korea, there's kind of feeling of resignation, that there's nothing much that can really be, I think, actually be done about it.

But I think one of the most important, I guess, like, help that we could as an NGO person, that we could get from the south korean or the government would be, I guess, the kind of information about what's happening both in North Korea and China. I'm saying this because even with, for example, like, the Punggy report that we recently published, we actually relied a lot on the previous work done by our own south korean government on this topic that wasn't really actually made public because for various political reasons.

And I think, obviously, governments have far more resources available, and also they have been collecting information about North Korea, not necessarily for human rights purposes, but perhaps for security or other reasons. And, for example, if we want to know the, one of the things that we are trying to do in the next phase is to collect information for accountability, work.

And in order to do this kind of work, we need to figure out the chain of command within North Korean security apparatus. And that's the kind of information that the governments have been collecting, again, for security purposes or other reasons for many decades. And also in terms of satellite imagery, to be honest, a lot of these kind of imageries are particularly expensive.

And also it's very difficult for the NGOs to have this kind of right expertise to actually analyze these pictures. So again, that's another area that I think the governments can be helpful. And I'm just saying this because I think, I'm thinking of the way that the Biden administration acted right before the russian invasion of Ukraine happened.

And at the time I was a little puzzled at the fact why actually the us government was releasing all this information about what the planned russian attack. And I was thinking, wouldn't this compromise the US information sources on the ground or citizen, whatever? But I think in retrospect, the US very actively pushing out this kind of information about what is basically about to happen very quickly prevented the Russians from even bothering to perpetrate this kind of false flag operation to justify the invasion.

And I think similarly, I think that line of work, that kind of work can be done on north korean human rights situation as well.

>> Oliva Enos: Very interesting, Tara.

>> Tara O: Yeah, that's a good question. And I have so many words. It's not just one, but I think attention to this matter, elevating this, and I know that's what this conference is all about.

But really elevating the human rights issues and expose any sort of human rights violations so that people know, so that those who are responsible can be held accountable. So I think that that is key, a lot of attention to this issue. And I know it's for the other panel, but really getting more information into North Korea.

>> Oliva Enos: That's a great one, Roberta.

>> Roberta Cohen: The main forum that deals with human rights in North Korea, the main forum that deals with human rights in North Korea is the United nations, and they became the main forum, particularly when the commission of inquiry report came out in 2014.

Next year will be the 10th anniversary of the COI report, and it's important that that be given. That's a good opportunity to give a lot of attention. But what have we seen at the United nations? There's a tremendous attack by China and by Russia, who also enable North Korea to undermine the United Nations' procedures on human rights.

So when you say what is needed, it's needed a strong coalition of states. Now let's just go back a few years, South Korea had stopped co sponsoring under the moon administration resolutions on human rights in North Korea. The United States, also looking at denuclearization possibilities, began pulling back as well.

So right now, under new administrations, UN and Biden, there is an effort to bring back strongly the coalition, South Korea, United States, European Union, and Japan to support strongly. And that's very important, the UN resolutions on north korean human rights and also to try to hold an official United Nations Security Council meeting on human rights in North Korea.

There was an unofficial one that took place a month or so ago, and that was important. But to get an official one, you need nine votes. And this is The Security Council is the most important peace and security body in the United nations. And the relationship of human rights in North Korea, the nature of that regime to peace and security has to be underscored.

To get those votes, you need a larger coalition, and I think that is most important to give the priority, building up a coalition at the undead that can actually get through a Security Council meeting, and that can bring to the fore, particularly on the occasion of the commission of inquiry report, all the information that should come forward publicly on the human rights situation in North Korea.

All the states are there. It is the main forum, and what is at stake is really the international human rights system. And finally to bring in the secretary general. The secretary general is for the entire United nations. But I always recall, as I did when I spoke, that this secretary general was also the high commissioner for refugees at one point.

And at that point, he did used to speak out. I even have a press release. I found from 2013, when he was the high commissioner for refugees, speaking out against the forced repatriation of North Koreans. He understands the issue. Of course, he is in a situation where he has to be brought into a UN coalition, but a UN really leadership on human rights in a part of the world that has been pointed out as one of the worst situations in the world.

And the 2024, when the commission of inquiry will be looked at after ten years, it would be important to get not only the states, but also the heads of the secretariat to be coming in on that. And that, I think, would be very important to do.

>> Oliva Enos: Yeah, I think it's so important, Roberta, that you're highlighting that the UN is such a forum and a force when it comes to the north korean human rights issue, because the CoI did fundamentally change the conversation.

I think that folks who focused exclusively on security issues now had to at least give a hat tip to the human rights violations that were occurring. And I think now that we're almost ten years on from the publication of the report, I think there's a real opportunity to elevate these issues even further and just remind people that this is ongoing.

This is not something that happened in the past. This is something that's happening in the present. And every single person should be alarmed that these types of human rights violations are continuing in the present. Okay, I wanna open it up to the audience for questions. Yes, sir.

>> Peter: I'm Peter Humphrey, intelligence analyst and a broadcaster in the Middle East.

I'm wondering if perhaps it's possible to incentivize the Chinese to let these people go. And that could happen in a bunch of ways. One, we don't probably wanna open up, but gotta think about it, is cash payments. Second would be alleviation of a particularly annoying sanction if these people were just simply allowed to leave the country and go wherever they wanted to go.

Is it possible to incentivize Chinese behavior? I mentioned this because next door in Kazakhstan, the UNHCR has been paying that country for years to maintain Uzbeks who escaped from the turbulence there and then moved across the border into Kazakhstan. Payments from UN High Commissioner for Refugees help maintain those people, setting the precedent for China with respect to north korean escapees.

>> Oliva Enos: Does anybody wanna take that? Roberta, first.

>> Roberta Cohen: Okay, first, you need a negotiating forum, and that's what is important to get through at this point. Where is it? And what is it? And here I really feel that if a few states would make this issue a priority, then you could get a group of states who could go to the secretary general of the United nations and try to look at how they can begin some kind of process of negotiation with China.

As far as exactly what to incentivize, I couldn't answer you, but I do recall reading the book of the German ambassador to the DPRK, who was there about eight years. And he talked about incentivizing negotiations, making incentives to North Korea during negotiations. That would be important to do exactly what they are, one can see.

But you need first this kind of forum, and that doesn't exist. And you need to be able to let China know that. What are the best arguments to bring them in to a discussion?

>> Oliva Enos: Ethan, you'd like to add something?

>> Ethan Hee-Seok Shin: Yes, thank you. So I just wanted to add a few points to what Roberta already said.

I guess the situation within China is actually a little more complex than is often assumed because so the central government, obviously, their main concern is this kinda geopolitical, maintaining good relationship with Pyongyang. Which is why they maintain this very full policy. But what we've noticed from the more grassroots or local levels is that actually there is not much support for this kind of policy, especially among the local authorities or the people.

And also many of the Chinese men in the Chinese rural areas that marry with the North Korean defector women, because basically thousands of them have already escaped to China over the past three decades. And many have actually married and started families with the Chinese men in these rural villages.

As you know, because of the one child policy, China has a very skewed gender-sex ratio, and which means that many of the rural men have nobody to marry. And so, in a very interesting, weird way, this has a very stable. It's actually a welcome development in many of these rural areas.

And if, for some whatever reason, the authorities decide Decide to arrest the North Korean women and have them sent back to North Korea, what you get, basically, is a husband without a wife, children without their mother, and basically a broken family. Basically, even the Chinese authorities, local authorities, are not really keen on actually doing, carrying out that kind of directive from the central government.

Especially because of the population decline in China these days, I think there is this kind of very complex internal dynamics within the country. I think kind of, if we can actually persuade China to kind of look at this kind of new reality that they're kind of facing, and if there can be this kind of interested governments making for concerted effort to actually sit down and have a serious negotiation with Beijing, perhaps the kind of some other working arrangement can be made.

This might not necessarily mean that China will recognize these North Korean women as refugees, but at least some difference, some form of legalized way of they can stay within China, for example. I definitely think if there is a political will, I think there is some things that can be done.

>> Oliva Enos: Excellent. Thank you. I think I saw a hand, Dave.

>> Dave Maxwell: Thank you, Dave Maxwell, and thank you for your great remarks and presentations. I guess I'm a little depressed because I hear great remarks from everybody, what international organizations are doing, what private, non governmental organizations are doing, which we all belong to, and then what governments are doing.

My question, and Roberta already partially answered this, but really, how do we generate synergistic effects among governments, international organizations, and non-governmental organizations to really better synchronize our activities? Because I think most, at least governments that support freedom and like minded democracies, most support human rights and want to see a change.

So I guess my one question is, who can be, who should be and can be the champion? And I think Roberta is right. We need UN leadership that's been lacking. But without that, how can we really generate synergistic effects? Is there a champion out there that can really mobilize all three levels of concerned parties?

Second question, what about organizations that work at cross purposes to human rights? Those that want to lift concessions and have end of war declarations and do things, have arms control agreements without human rights being considered. Those who would, who would say we should not address human rights? How should we collectively address those types of organizations and positions?

Thank you.

>> Oliva Enos: Thank you, Dave. Who wants to take those two excellent questions first? Tara.

>> Tara O: Is this on? I will focus on what's happening in South Korea. They actually passed a North Korean Human Rights Act, and it was enacted in 2016, but the problem is it really hasn't been implemented because again, a lot of opposition within the that party I told you about.

But one of the things that law did was to create North Korea database center. And they recently, so in the name of south korean government, published a north korean human rights report. This was, they interviewed over 500 defectors in the last five years and they couldn't publish it earlier because again, last administrator wouldn't allow this.

But finally it was published. They have that being done. I think they did that in conjunction with the unification ministry. And the law also stipulates that it creates North Korean Human Rights Foundation because when, if this comes into being. Then it'll coordinate with all the different defector NGO's and other NGO's, especially ones sending leaflets or any other activities that's related to North Korean human rights in South Korea.

Again, the creation of this organization, because this is foundation. So it means a lot of funds will flow. All the funds were cut off during the Moon administration. With this, it'll actually help support them and help coordinate. But again, it stuck because it says that the current ruling party nominates, I think, three or five board members and then the Tae Woo Minju Party, they're supposed to nominate five board members, but they're not doing that.

So if you don't have board members, it can't exist. And so that's where the issue is. So maybe if there's some greater pressure, international pressure, to have that organization or implement the law so that this can be created, I think there could be a lot more coordination with NGO's and at least with South Korean government at that level.

>> Roberta Cohen: Dave, what are those questions?

>> Oliva Enos: Microphone.

>> Roberta Cohen: Very loyal. First of all, I think there's a war of ideas that is going on, and I think it's very important that in that war of ideas, you heard that really this morning in the introductory remarks. Does human rights have a role to play when nuclear weapons are on the table?

And that answer that the nature of the regime, and I think Greg was doing a good job of setting that forth. The nature of the regime is really going to be very significant. Can you really have peace without attention to human rights? I think there ought to be even just a piece of paper that begins to be circulated on how you challenge those who say human rights has to be put aside.

And that, I think, was part of the Moon administration. I mean, their supposed goal was to get denuclearization, and they really were the proponents of putting human rights out the window. You can't deal with that at all. I think that argument, I mean, that ought to be something that can really be tackled here and brought many places and HRNK is beginning to do that.

But you have to see there is a war of ideas. Secondly, there are some appointments that could be quite relevant here to promoting some kind of greater unity. One is that the Yoon administration in South Korea has appointed a special envoy on human rights in North Korea and the United States has nominated a special envoy for human rights in North Korea.

There, I think those in the US who can speed up the process of getting that person actually confirmed. She testified yesterday. There's another person, and then of course there's the UN Special Rapporteur on human rights in North Korea. So you have in different parts of the world and I think the three of them, if they could come together, I mean, they have different mandates and different objectives, but there's a way that the three of them can work together.

So that there is the kind of unity on this issue. And so let us hope for that. But then I can't help remembering, because you hear it mentioned time and again, can you get a movie star, someone that is associated with the idea of promoting human rights in North Korea?

And I can think of a number, but somebody has to go get them and they can be very effective because you see that in different countries of the world, when somebody movie star gets involved, suddenly there's more publicity. So I think that would be something also to think on, although that's a little bit of a dream.

>> Ethan Hee-Seok Shin: So again, it's, yeah. So as an NGO person, I think the first question kind of felt like whether the chicken comes first or the egg comes first, I think the UN obviously has a very important role of legitimizing or actually facilitating this kind of process. But at the same time, the UN actually it moves in the initiative of the member states.

So how do you get the governments on board? So I think just going back to the COI experience, that has been the challenge for the NGO's to actually engage both the UN side and also the national governments to push this kind of initiative. And I think the COI 10th anniversary will hopefully be a good occasion to push for this kind of activities.

And I think, at least from where I come from, South Korea, I think one, I guess the problem with difficulty has been that we haven't had this kind of very well established control tower for north korean human rights policy. So even though our president speaks a lot and very strongly, vocally about North Korean human issues lately, there is no administrative structure to actually implement what he is saying.

So I think Japan's example of having this kind of a headquarter for the abduction issue headed by the prime minister, that kind of institutional changes probably will be helpful. But I don't think there's that kind of political development yet. So, yeah there.

>> Oliva Enos: So we're running up against the clock here, but I can take a couple more questions.

Yeah.

>> Henry: Hi, Henry Song, activist and also director for One Korea Network based here in DC. Great panel so far. I'm looking forward to the rest of the day with the other panelists. The question I have is, once the COVID restrictions are loosened for North Korea, and Roberto, you mentioned that this is kind of well known fact among the activists and defectors.

But the hundreds of the defectors that are being detained in China right now, the worry that the defectors and activists have is that once they're able to repatriate these defectors back to North Korea. That's obviously a big concern for defectors and families in South Korea and here in the US as well.

And some of the calls that I've been getting from South Korea, these are from both defector activists, from south korean missionaries and pastors, is that some of these defectors that have been arrested. Especially the ones that have been arrested earlier this year, they have been already moved to the border area, ready to be transferred to North Korea.

So I guess my question is, how do we prepare for what many defectors believe will be an onslaught of the repatriation of these North Koreans back to North Korea? I think a lot of the points that have been made, they're excellent points. We have, in a way, a great environment in terms of Ambassador Lee Shino of South Korea and Miss Julie Turner.

She did a great testimony at a confirmation hearing yesterday. We have administration in South Korea and here in the US that's very strong in terms of human rights. So how do we, I guess, leverage that and prevent what the most fear will be the large number of repatriations that will happen in the next, I don't know, weeks, months.

So that's my question. I'd like to hear your opinions regarding that. Thank you.

>> Oliva Enos: Roberta, would you like to take that one? Microphone?

>> Roberta Cohen: Yeah. I wish I had a very good answer for you, because it's a case that's before everyone, and if people are turned back, they're going to be punished.

So I think when I spoke, I mentioned a few options, but they take time, I mean, getting governments quietly to go and begin to try to get the secretary general. Try to get leaders that have some access to China, and then when it comes on the north korean side to make a lot of noise, maybe this could help some of these people to make it seem as if North Korea is, there's a focus on North Korea.

Would there be any possibility that they would try to avoid all that publicity by not subjecting these people to the kind of ill treatment and inhuman punishment that they do? I can't think of any other way. This has been going on for several years. The international governments are quite distracted by the war in Ukraine and by other conflicts around the world.

It's not easy to get their attention. What I mentioned was a small and cruel refugee situation. There are also millions of people on borders. So you really have to find, identify who can be of assistance, who can try in this case. And I'm not sure, as I mentioned, whether UNHCR is on this task or not.

They ought to be. I think that it would be good if you can go into the UNHCR office in Seoul to see what they can do, headquarters to make a fuss there. I just think you need some good publicity and also some quiet diplomacy going on the scenes.

But it's not and it's a challenge to accomplish that.

>> Tara O: I agree, especially the latter part. As far as quiet diplomacy, South Korean government can actually request Chinese authorities to release all or some based on maybe different situations, because they have done that before. So that is something that can be done again, maybe more often by the South Korean government.

So that's one thing. And the other is, again, although they violate human rights, they also care. They also care what the international community think. So I think keeping attention focused on that matter, whether maybe with the help with the media, just keeping the attention out there, I think that will put some pressure on those regimes.

So those are the two that I can think of.

>> Oliva Enos: That's great. Well, I think we've come to the end of our time here. I know that I definitely feel better educated on the landscape of North Korean human rights issues, and hopefully you all feel the same. I just wanted to issue a final thank you to the NED for offering this beautiful space, the Hoover Institution as well, and to HRNK for allowing us to all convene together today.

And hopefully, this was a good first panel to kick off all of our discussion. Thank you all, and please join me in a final thank you to our panelists.

>> Ethan Hee-Seok Shin: Thank you.

PROGRAM AGENDA

8:45am | Welcome and Opening Remarks

Damon Wilson

President and CEO, National Endowment for Democracy

Dr. Larry Diamond

Senior Fellow, Hoover Institution; Mosbacher Senior Fellow in Global Democracy, Freeman Spogli Institute for Int'l Studies, Stanford University

Greg Scarlatoiu

Executive Director, Committee for Human Rights in North Korea

9:15am | Refugees, Prison Camps and the Chinese Dimension

The Honorable Roberta Cohen

Co-Chair Emeritus, Committee for Human Rights in North Korea

Dr. Tara O

Adjunct Fellow, Hudson Institute

Ethan Hee-Seok Shin

Researcher, Transitional Justice Working Group

Olivia Enos, moderator

Washington Director, Committee for Freedom in Hong Kong

10:30am Break

11:00am | Empowerment through Information

Colonel David Maxwell

Senior Fellow, Foundation for Defense of Democracies; Board Member, Committee for Human Rights in North Korea

Dr. Jieun Baek

Research Project Manager on Technology and Human Rights in North Korea, Carr Center at Harvard University

Lynn Lee

Deputy Director for Asia, National Endowment for Democracy

Hyun-Seung Lee

Fellow, Global Peace Foundation

Christopher Walker

Vice President for Studies and Analysis, National Endowment for Democracy

12:30-1:30pm Lunch

1:30pm | The North Korean Human Rights Act: Implementation, Problems and Prospects

The Honorable Robert King

Former U.S. Special Envoy for N. Korean Human Rights Issues; Board Member, Committee for Human Rights in North Korea

Dr. Nicholas Eberstadt

Henry Wendt Chair in Political Economy, American Enterprise Institute; Board Member, Committee for Human Rights in North Korea

Ethan Hee-Seok Shin

Researcher, Transitional Justice Working Group

Greg Scarlatoiu, moderator

Executive Director, Committee for Human Rights in North Korea

3:00pm Break

3:15-4:30 pm | A New Approach to North Korea Policy: Human Rights up Front?

Dr. Kim Dong-Su

Senior Advisor, Institute for National Security Strategy

The Honorable Robert Joseph

Former Under Secretary of State for Arms Control & International Security; Board Member, Committee for Human Rights in North Korea

The Honorable Joseph DeTrani

Former U.S. Special Envoy for Six-Party Talks with N. Korea

Dr. Larry Diamond, moderator

Senior Fellow, Hoover Institution; Mosbacher Senior Fellow in Global Democracy, Freeman Spogli Institute for Int'l Studies, Stanford University

If you have any questions about this event, please contact Abigail Skalka.

Twitter: Follow @NEDemocracy and use #NEDEvents to join the conversation.

Please email press@ned.org to register as a member of the press.