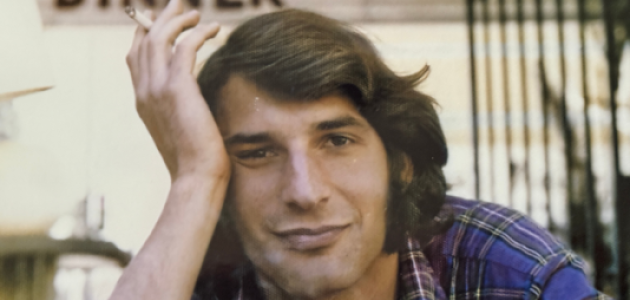

Lt. Col. Oliver Lause, representing the US Air Force, is a National Security Affairs Fellow for the academic year 2021–22 at the Hoover Institution.

A graduate of the US Air Force Academy and a career fighter pilot, Lause has served as a fighter squadron commander in South Korea, an instructor at the US Air Force Weapons School, aide-de-camp to the commander of US Air Forces in Europe and Air Forces Africa, and most recently in the office of NATO’s Supreme Allied Commander Europe and commander of US European Command.

Lause has flown combat missions in Afghanistan, where he said pilots faced the challenge of providing close air support for US and coalition personnel fighting a counterinsurgency campaign while adhering to rules of engagement in order to avoid civilian casualties.

Finally, Lause has been spending his time at the Hoover Institution, which he describes as an extraordinary opportunity to conduct open-ended research on how the US military should best design and execute a twenty-first-century deterrence strategy—applying conventional, cyber, economic, and information warfare along with other capabilities—in the increasingly contested threat landscape of strategic competition.

Why did you decide to join the US Air Force?

Oliver Lause: When I was in high school, I had a very turbulent family situation which required a lot of sage advice, support, and even legal counsel. The folks who stepped up to help didn’t have to, but they did because they felt it was the right thing to do. The result was a positive outcome and a very maturing experience. At a young age, it cemented the ideas of service, contributing to things larger than yourself, and the importance of preserving a society grounded in freedom and the rule of law.

Growing up in Colorado, I was considering the US Air Force Academy, especially as a path to fulfill a childhood dream of becoming a fighter pilot. I also looked at West Point. The decision was easy in the end. I felt a duty and responsibility to serve after those experiences in high school … most importantly, that our society—messy and complicated as it may be sometimes—is worth defending. So, off I went to the Air Force Academy.

Will you tell us about your educational background?

Oliver Lause: I went to the Air Force Academy thinking I’d major in engineering. Then I took my first political science class and was hooked on discussions and study of national security, the foundations of democratic societies, and international relations theory. The calculus was really simple—as a future officer and pilot, why not study a subject that would help me better understand why and how our political leaders choose to employ military power? Nevertheless, like all other Air Force Academy cadets, I was still required to fulfill a hard science curriculum, which included physics, calculus, astronautical engineering, and thermodynamics, to name a few.

Later in my career, I received two master’s degrees, one in military operational art and science and the other in airpower strategy and technology integration from Air University. Officers from all the service branches usually receive something resembling the first degree. The second degree was related to a fellowship for the Air Force Chief of Staff. Its focus is strategy and the future of technology in warfare. For a year we explored the research question, “How do we prevail in highly contested environments in 2040?”

Each day was a critical thinking exercise. We basically read a book and a half per night and then synthesized what we learned in a seminar the next day. We did this for roughly five months before transitioning to war games, visiting research labs and many parts of the private sector, and conducting individual and group research. For my individual research, I spent time focusing on cyberspace operations at the National Security Agency, our Air Force operations floors at what used to be known as 24th Air Force (now 16th Air Force), and in some of our federally funded R&D facilities.

The opportunity to war-game with several think tanks was eye-opening for a mid-level officer. Places like the Hoover Institution and think tanks on the East Coast employ many experts who have never served in uniform. However, we quickly realized many of these people were running circles around some of the ideas we had about strategy, warfighting, and national security. It was a humbling and an important developmental experience about the diverse array of people and organizations we have working to defend America.

Will you tell us about your career arc as an Air Force pilot?

Oliver Lause: Following graduation from the academy, every newly commissioned officer receives sixty days leave. Instead of taking the time off, I interned on Capitol Hill for a US senator who was a member of the Armed Services Committee. After that, I transitioned to pilot training, where I was fortunate enough to earn my first choice and go fly the F-16. I wanted to do this because of its ability to conduct air-to-air and air-to-ground missions.

My first few years in the F-16 took me to what we call a remote assignment in South Korea and then to Shaw Air Force Base in South Carolina. During this time, I deployed to Afghanistan. Toward the end of that assignment I was selected to attend the US Air Force Weapons School at Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada. Graduates of the five-month program become weapons officers, which means that they are considered tactical experts and leaders to integrate air, space, and cyber power on behalf of the joint force. After Weapons School, I did another remote assignment to South Korea as the weapons officer in one of our fighter squadrons.

Immediately after Korea, I had the opportunity to return to instruct at the Weapons School. Following three years teaching, I participated in the fellowship that we discussed earlier. Along the way, I served in a few staff positions and these helped me better understand the organizational structure and functions of the Air Force and the Department of Defense. In one assignment, I served as the aide-de-camp to our commander of Air Forces in Europe and Air Forces Africa. After a short time flying F-16s out of Spangdahlem Air Base in Germany, I was sent to command a fighter squadron in South Korea—which is probably the highlight of my career to this point. There’s nothing like command and the responsibility to have your unit ready to fulfill its wartime responsibilities while leading the people entrusted to your care. After that assignment, I went to Belgium where I spent the last two years working directly for the Supreme Allied Commander Europe and commander of US European Command.

Why do you feel the effort was worth it in Afghanistan despite the way the US withdrew?

Oliver Lause: In the grand scheme of things, I would argue that we are safer today. Violent extremist organizations—or transnational terror groups—are much harder pressed to successfully execute a 9/11-style attack.

Given the blood and treasure spent on Afghanistan, many have wondered: Was it all worth it in the first place? But it's so easy to forget what we felt like on September 12 and that October when we began operations in Afghanistan—which most didn’t realize because we were focused on the anthrax scares in the states. Those times shook the psychological stability of our society. People wondered when they would comfortably take public transportation or go to the mall again. The confidence in our security needed to be restored, and for that reason, I would have to say the cause was worth it.

Like many, especially those of us who directly participated in the fighting, you have to take time to reflect on the experiences. In the case of a counterinsurgency campaign such as the one the United States waged in Afghanistan, we were charged with building trust with the population so they could build capability and capacity in order to be responsible for their own defense. While we adhered to a simple idea—do no harm—we needed to eliminate threats whenever possible within the rules of engagement. In those efforts, we had to operate with a high level of transparency. Those were very challenging missions, made more so when you look back and think of the people who never returned home.

Now, to the objectives of stabilizing Afghanistan, in the hopes that it wouldn’t be used as a base for future attacks, it’s certainly frustrating to see a two-decade-long war end in such a fashion. Despite the way it ended, we shouldn’t ignore the massive evacuation that successfully got over 120,000 Afghans out, while recognizing that still continues today through private efforts and humanitarian organizations. Especially in long campaigns, it becomes difficult for the American people to connect how military objectives help fulfill national policy goals. The only way we can sustain US force commitments is if the American people believe that the cause is worth the sacrifice.

What do you hope to accomplish during your fellowship at the Hoover Institution?

Oliver Lause: I have used this extraordinary opportunity to both broaden and deepen my perspectives and access the diverse expertise and the wealth of archival material Hoover has to offer. I have been especially focused on the concept of twenty-first-century deterrence, the structure and history of the National Security Council, and the history of civil-military relations.

The deterrence strategies we currently implement are much more complex than Cold War models, with unique levers like cyberspace, the increasingly interconnected nature of our global economy, and the information operations we’ve seen attempt to influence everything from elections to public debates of COVID-19 policies. The basic principles of deterrence remain the same, but the potential frameworks are different, especially with a very aggressive and capable Chinese Communist Party that’s competing in all domains across all instruments of power.

Creating effective whole-of-nation and whole-of-government approaches is very challenging to do. And just as it’s difficult to do so across the instruments of power and the domains, it’s difficult to do in the Department of Defense with a variety of operations, activities, and investments across the combatant commands and within the services. That’s exactly what the new National Defense Strategy’s articulation of integrated deterrence is driving on. I’ll admit, it’s easy to critique yet another buzzword in front of the word “deterrence,” but we’re all in this together, trying to craft the most effective policies that keep the global security environment as stable as possible. As we’re seeing in Ukraine, that’s no easy task and it’s not going anywhere either.

Studying the history and various structures of the National Security Council [NSC] has been very informative. We can have the best trained military with some of the most sophisticated weapons in the world, that’s backed by the most powerful economy, but they will be ineffective if our decision-making processes aren’t well integrated and struggle to keep pace with the speed of relevance in the threat environment. There aren’t any panaceas here or some magical reorganization that makes the challenge of crafting and implementing effective policy go away.

One of my biggest takeaways so far is the variety of models the NSC has operated under that provide avenues to successful decisions. Like anything most have experienced in their lives, the functionality depends on doing the hard work to present information and deliberate decisions in ways serving the strengths of the decision makers, working through personality and organizational conflicts to share information in the debate, and having a process the organization routinely executes so we aren’t missing critical pieces of the analysis. These are all difficult, but the last one perhaps most of all.

One of the rabbit holes I dove in this year is reading a lot of national security and deterrence literature from the 1940s to the 1960s—a comparable time in terms of the scope and scale with which we were grappling with our security situation, uncertainty in the world order, and the specter of something new and horrific in the form of nuclear weapons. There are many differences and many parallels with today, along the lines of “history doesn’t repeat but it often rhymes.” Henry Kissinger writing in 1965 talked about the central tension of bureaucracy and inspiration in our organizational decision-making process. We’re striving for bureaucracy or process that takes care of “problems as a matter of routine, but not so pervasive as to inhibit creative thought that is inseparable from true leadership.” Add very persuasive personalities and organizations into the mix, and that’s essentially the persistent challenge of the NSC at all times.

I’ve also spent time researching the history of civil-military relations. If you go all the way back to the 1930s, there’s a real or perceived civil-military crisis every handful of years or so. The principle of civilian control of the military is something we hold dear, but power, policy-making differences, and the risk of involvement in partisan politics always encroach in the challenge to provide best military advice for our security. My biggest takeaway is rather simple: we have to continue to stress and uphold our apolitical ideal as military officers. This doesn’t mean we’re naïve to the political ends the military will be tasked to achieve, nor the political nature of the activities inherent in policy making. It is only in aiming for the high ideal of an apolitical military that we reach the target of helping craft effective national security policies, winning our nation’s wars, while recruiting and retaining citizens eager to serve such causes.

Beyond these research interests, it’s been a fantastic year to reconnect and recharge with my family. I can’t thank my family enough. Our families are often the ones who serve as much or more so than the airmen, soldiers, sailors, marines, guardians, and coast guardsmen they support. I’m so proud of the character and resilience my wife and kids have shown through the years.

Can you tell us about your experience advising the Stanford undergraduate mentees?

Oliver Lause: As NSAFs, we have the unique opportunity to mentor Stanford undergraduates who are interested in national security policy. This gives us a chance to influence young people who might not otherwise consider public service. Reciprocally, the program benefits the student mentees. It provides an environment in which they can receive perspectives from diplomatic and military professionals to think critically about public policy. This is especially important if you think about the arc of their lives. The war on terror was well underway when many were born, some recall the 2008 financial crisis as a very disruptive event of their youth, and their teenage years have been indelibly shaped by a deeply partisan political environment operating during what can be described as an era of information warfare over social media. But if any had doubts about what this global environment of strategic competition might look like and what is at stake, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has answered those questions.

I’m incredibly optimistic about America’s future after spending almost a year engaging with these students. We hear a lot of negative things about this generation, which was probably said about my generation and countless others. But when you look at the experiences they’ve grown up with and see the desire they have to learn about our global challenges, while being hungry to make their mark … it’s refreshing. I’m deeply impressed by their talent and the ideas they bring forward. If we can get many of them involved in public service or private sector efforts that help steer and influence our public enterprises, we can drive solutions to many of our challenges as a nation.

What does leadership mean to you?

Oliver Lause: A simple way to talk about leadership is “mission first, people always.” In the military context, the “mission first” aspect is about defending America by deterring our adversaries. The “people always” piece means we’re continuously focused on caring for the most important resource in the Department of Defense—the talented Americans who volunteer to come to work every day.

If you think about different ways to influence people, they include on a spectrum: inspiration, incentivization, and intimidation. General James Mattis always reminds people that inspiration beats intimidation every time. If you're inspiring people, then they are more naturally willing to perform and to step up to be the leaders of the future. Incentives and intimidation are certainly part of your tool kit as a leader, but you’re always aiming to inspire your people so their motivation to serve and accomplish our missions continues to come from within.

I have a couple simple, foundational phrases from a priorities and behaviors perspective and they’re what I talked to my folks about as a fighter squadron commander. The first is the three R’s: readiness, relationships, and retention. Readiness covers our warfighting capabilities and skills, and it’s the thing that matters most to what we provide in the military. Relationships have to be healthy and professional across our organizations and up and down our chains of command. Finally, retention means developing personnel and providing them and their families with a certain quality of life that in turn allows them to sustain the demands of serving in the military.

Those things certainly aren’t easy, but we build them through the three T’s: trust, teamwork, and training. Trust—as the late, great Secretary George Shultz reminds us—is the coin of the realm. It sets the foundation for healthy and productive relationships which foster the teamwork essential to integrate the talents of our people, the services, and their capabilities. And finally, we maintain a laser focus on training, constantly sharpening our warfighting edge to deter and defeat adversaries when the nation calls.

A couple of these things are ideas and actions I’ve adopted from good examples over the years. That’s an important aspect of leadership—humility. You’re not going to have all the answers. Driving organizations to success is a team sport. We have to listen, learn, share, and borrow from each other to create the type of committed, inclusive environments that lead to achieving our objectives – and those actions simultaneously allow us to be effective leaders of those incredible organizations.