- Education

- K-12

- Reforming K-12 Education

To become more equitable, school choice needs to become as extensive for all families as it is for affluent ones, who currently enjoy high-quality schools by purchasing a home in expensive neighborhoods. Charter schools need to be expanded in number and size, especially at the secondary level. Private-school vouchers and tax-credit scholarships should be made available statewide to low-income students. Large school districts should offer a portfolio of autonomous schools with a variety of curricular and pedagogical approaches.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Inasmuch as school choice is nearly universal in the United States, then opportunities for choice need to be as equitable as possible. The question is not whether to have choice, as the issue is usually posed, but how to have choice, given its pervasive reality.

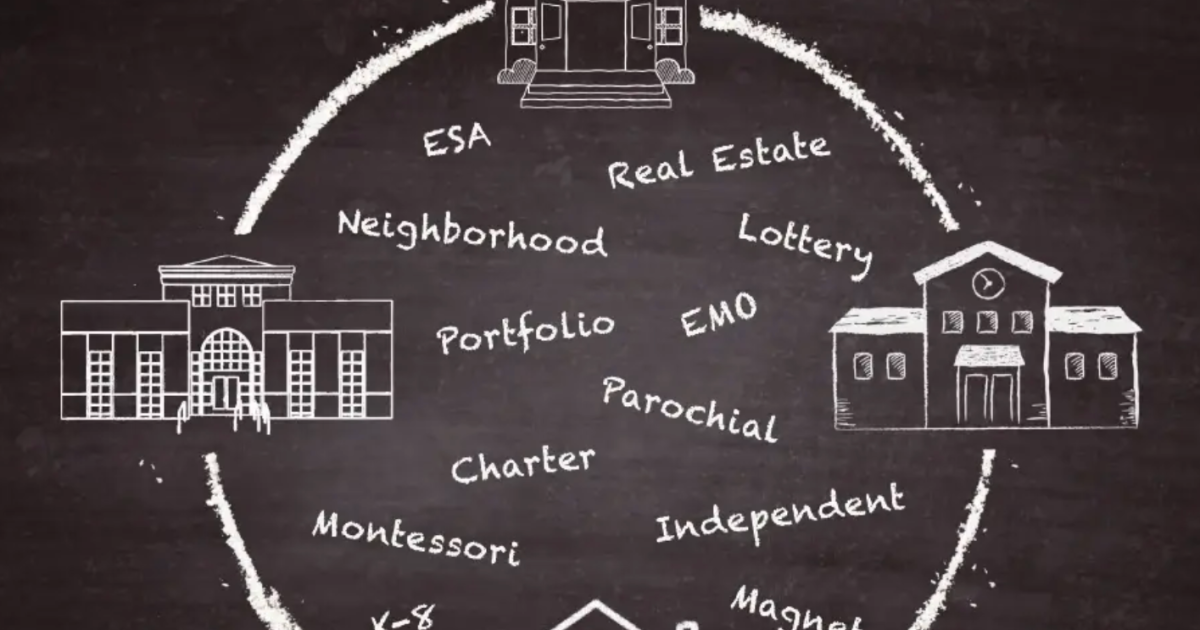

Choice is an inherent feature of the American education system. The right to a private education is guaranteed by the Constitution. And public schools allow families to choose their school when selecting the neighborhood in which to live. Given the nation’s size, complexity, and modern modes of transportation, residential choice is a fundamental component of American education. Critically, this form of choice favors those with more economic and cultural resources. To provide more equal educational opportunity, new forms of choice—magnets, open enrollment, portfolio districts, charters, vouchers, tax credits, education savings accounts—have emerged in recent years to supplement choice by residence. Even more advanced forms of choice are now on the horizon, especially in the wake of the COVID-19 crisis: digitally aided homeschooling; micro-schools with specialized curricula; course choice, which allows students potentially to use different providers for each course; and neighborhood pods assisted by tutors.

These new forms of choice have not fully transformed American education. Only about 15 percent of the student population is making use of these new choice opportunities, and apart from the education provided by a relatively small number of outstanding charter and magnet schools and access to high-quality private schools for low-income families, the quality of the educational experience at the new schools is often not dramatically different from that available through assigned schools. For affluent families, the new forms of choice offer very little, as the schools they choose by residential selection are often socioeconomically and ethnically homogeneous havens of learning opportunity.

Yet the steps taken toward creating new forms of school choice are offering a wider range of better opportunities to children from less advantaged backgrounds. In many places, these students are performing better on tests of achievement in math and reading than those assigned to a district school. They are likely to continue beyond high school at higher rates than those in district schools assigned by residence. They are at least as likely—and probably more likely—to acquire desirable civic values than those assigned to a school. Parents express higher levels of satisfaction with choice schools than assigned ones. The demand for more choice opportunities exceeds the supply of choice schools available. Importantly, choice schools are improving with the passage of time. Choice schools, as compared to assigned ones, have adapted more quickly in the face of extreme emergencies, such as Hurricane Katrina and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic.

Nor do choice schools have baneful effects. Choice schools do not have a negative impact on the performance of students at assigned schools, and they have little impact on the degree of ethnic segregation in the United States. To the extent that segregation increases, it is at the will of minority families who choose desired schools regardless of ethnic composition. The costs to the taxpayer of charters, vouchers, and tax credits are less than those of assigned schools. Nor do choice schools have a negative fiscal impact on the per-pupil expenditure levels of assigned district schools.

New forms of choice are hardly perfect, but they are a notable advance from the old system of residential choice. Yet they encounter stiff resistance. School districts are stoutly defended by school boards, school superintendents, many teachers and the unions that represent them, as well as by high-income better-educated families who prefer homogeneous educational settings for their children. Given the opposition, the new, more equitable forms of choice cannot be expected to fully replace residential choice, but their popularity among parents and students is expected to increase.

Six Principles to Guide Future Action

1. States should encourage multiple forms of school choice.

2. US education needs greater flexibility and adaptability than what is currently offered by a rigid system of elementary neighborhood schools and comprehensive high schools.

3. A family’s choice of school should not be distorted by fiscal policies that favor one sector over another.

4. School choice should facilitate desegregation.

5. The focus should be on enhancing choice in secondary education.

6. Choice by itself is not enough.

Specific Actions

All Sectors

A. Encourage common enrollment systems across district, charter, and private sectors.

B. Arrange for and cover the cost of comprehensive transportation systems that provide equal access to all students regardless of school sector.

C. Provide special education in a wide range of settings without imposing specific numerical constraints on certain schools or networks. Parents should be given opportunities to choose programs from the district, charter, and private sectors.

District Sector

D. Provide schools in portfolio districts with the autonomy needed to offer a diversity of genuine choices among quality schools.

Charter Sector

E. Facilitate charter growth by fostering both proven providers and minority entrepreneurs.

F. Pay attention to charter school authorizer quality.

G. Relax charter teacher-certification rules.

Private Sector

H. Consider tax credits as alternatives to vouchers.

I. Broaden income eligibility for private choice programs.

J. Preclude low-quality private schools from participating in government-sponsored programs but resist the temptation to regulate the private sector.

Click here to download the executive summary.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Paul E. Peterson is the Henry Lee Shattuck Professor of Government and director of the Program on Education Policy and Governance at Harvard University; a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University; and the senior editor of Education Next: A Journal of Opinion and Research. He received his PhD in political science from the University of Chicago.

PREVIEW: TOWARD EQUITABLE SCHOOL CHOICE