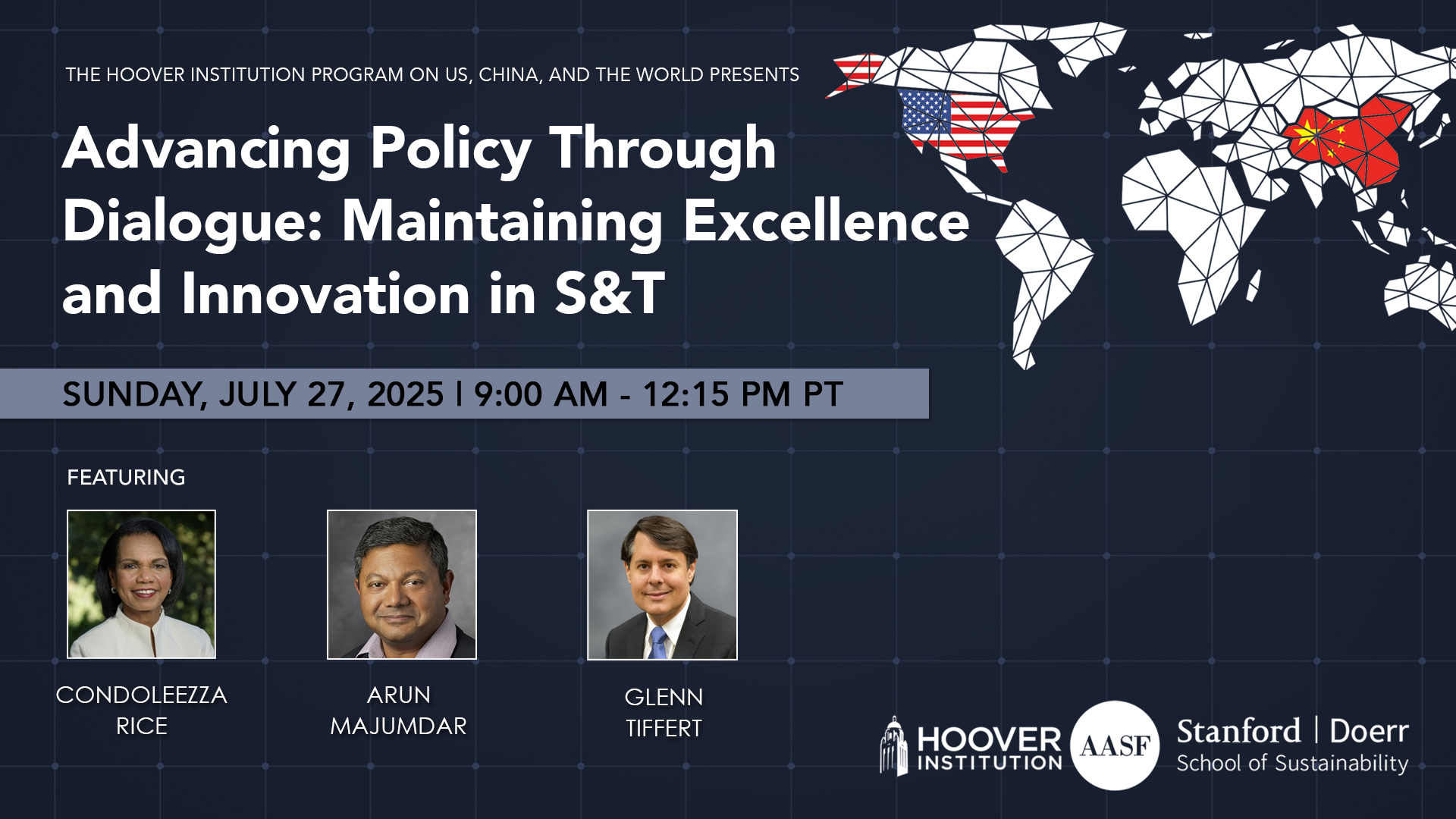

The Hoover Institution Program on the US, China, and the World hosted Advancing Policy Through Dialogue: Maintaining Excellence and Innovation in S&T on Sunday, July, 27, 2025 from 9:00 am - 12:15 pm PT in the Memorial Auditorium, Stanford University.

How can the United States maintain global competitiveness and leadership in science and technology (S&T)? How should scientists, innovators, and policy makers navigate a complex geopolitical environment where leadership in S&T is foundational to national and economic security? The Hoover Institution’s Program on the US, China, and the World, in partnership with the Asian American Scholar Forum, is honored to host distinguished experts from government, academia, and industry for a series of fireside chats and roundtable discussions to address these and other critical issues facing the scientific research community.

This programming was part of the 2025 Asian American Pioneer Medal Symposium and Ceremony and was free to attend.

For more information about the Program on the US, China, and the World, click here.

For more information about the Asian American Scholar Forum, click here.

>> Glenn Tiffert: Thank you so much. On behalf of the Hoover Institution and our program on the U.S. china and the world, it's a great pleasure to welcome you to a morning of policy discussions around science. Science is a process of discovery and of knowledge production, but it's also much more than that.

It has the power to change our understandings of who and what we are, our relationships to one another, and the conditions of individual and collective welfare. For those reasons and many more, science is all of our concern. Science policy is a large and growing part of the Hoover Institution's research portfolio.

We are a public policy think tank at the heart of one of the world's great universities, Stanford, in the middle of one of the world's great innovation clusters, the Bay Area. We study how science is governed, the economic, social, institutional, and geopolitical dimensions of it, and how scientific talent is nurtured and replenished.

We publish scholarship on the competition in critical technologies, and we create data and tools to help our research enterprise manage the risks posed by an increasingly complex global environment. And we do this in partnership with stakeholders from across academia, government, and industry in both the US and around the world.

We're proud of the collaboration with AASF that made today possible. And I thank you, Yasheng Yi Gazella, Secretary Rice, and all of our other participants for helping us put together what I know will be a very informative, rich, and engaging program. I salute all of you from different walks of life, including diplomats from around the world who are here today who have chosen to spend part of your morning with us.

And so that we can dive right into our program, I know that our next speaker needs no introduction.

>> Arun Majumdar: Great. Great. Well, folks, you're in for a treat. Over the past two days, we celebrated the achievements of some outstanding Asian American scientists, entrepreneurs, policymakers, media personalities, and all of you.

I call it the Asian American Oscars. And actually, you got a feel for that yesterday. These people have really shaped not only the trajectory of the United States, but of the world. And so when we reflect upon their accomplishments, we are compelled to ask the question, how did this happen in America, a land 10,000 miles away from Asia?

Right. I like the way, you know, Jensen said, you know, I am the American dream. Remember that? Yeah.

>> Arun Majumdar: So how did this happen here? And the answer lies in the American DNA, which was beautifully articulated by President Reagan, who reminded us, quote, we lead the world because unique among nations, we draw our people, our strength, from every country, every corner of the world.

And by doing so, we continuously renew and enrich our nation. Beautiful words. So it is precisely this American DNA that has drawn talent from around the globe, particularly from Asia. And the journey often begins at the intersection of higher education and enterprise and businesses. So under this American ideal, we are not defined where we came from, but what we have to offer, what we are capable of.

So yet, as we honor these accomplishments, we must also confront some current realities. While the United States enjoys very strong relationships with many Asian countries, the US China relationship has soured. And this has profound implications on the global economy and our security. And it is demanding us to rethink our own global engagement, our security commons that we call so here at home.

And this has been kind of an undertone. I just want to bring the elephant, introduce the elephant in the room. This has heightened some anxiety amongst Asian Americans. It's raised critical questions, how and why did these. These things change? Are these shifts reversible? How will the US-China tension impact how we treat our Asian-American citizens?

What are the key risks or opportunities to trend and the trends that shape the geopolitical landscape? I know these are in your minds. I've heard them anecdotally. Fortunately, as you heard, we have someone who is uniquely qualified to address these issues. Secretary Condoleezza Rice. As you heard, she's been the provost, she's an academic, she's a scholar.

She has shaped and learned, educated on the history and also shaped the US History and the global history as well. There are few people who have the breadth of experience across government, academia and business. So, Secretary Rice, let me open a conversation with a few questions. Then I'll welcome some of the questions from the audience.

Let's start close to home. When we launched the Door School of Sustainability and you join Advisory Council. Thank you. I remember asking you what should be an international strategy, and you answered without hesitation. Southeast Asia, Indonesia in particular, and India. So what led you? What was behind that?

>> Condoleezza Rice: Well, first of all, thank you very much for having me, Arun, and you will call me Condi. I haven't been Secretary Rice for a number of years now. But in any case, I think that we have to look past the current geopolitical situation to countries that are in a position to make a move to become economic and indeed political powers in the world to come.

And Indonesia is a very interesting country. Huge population, young population, difficult to govern because it's an archipelago. And I've had a lot of experience with Indonesia when it was going through a difficult period of terrorism and the like. But it is a population that is ready to take the future and one of the things that we know is that economists will tell you that one of the greatest predictors of future future GDP is your demographics.

And so that's the case for both Indonesia and for India, where in the Bush administration we made some steps to improve and indeed take our US-India relationship to a different level. Through a civil nuclear agreement that got rid of all of the restrictions that had been put on India for many years because of its nuclear program and to enhance defense cooperation, scientific and technical cooperation.

These are two giants. And I think recognizing that is extremely important. It's also the case that both have work to do, and they understand that, because when you have a young population. You have to make sure that everybody has an opportunity, that everybody is educated. And if you look at India, for instance, something Arun, that you know personally, the IITs are remarkable.

You yourself are a product of the Indian, the Indian university system, which is extraordinary, but there's still too many people trapped in Calcutta. And so the issue for these countries, and I think we have a stake in their succeeding in doing it, is to bring this young population, give everybody a chance and tap that potential that may be not tapped if first class education is not available to everyone.

Problem we have in the United States too. But I think for India and for Indonesia, big populations, this is an extremely.

>> Arun Majumdar: Important question for Indonesia in particular. I mean, they are the headquarters of asean.

>> Condoleezza Rice: Yes.

>> Arun Majumdar: Are there some lessons from ASEAN that could be really useful in sort of international trade?

>> Condoleezza Rice: Well, I think ASEAN has some contradictions within it because while it is true that Indonesia, Vietnam, Malaysia, we had very good relations with all of them, Myanmar has been a problem. And I think the inability of ASEAN to really speak to the struggles and to the desires of the people of Myanmar has made ASEAN less effective than it could be.

But yes, as a trading bloc, because of the importance of those economies, several which have made some progress in terms of human rights and political freedoms. Yes, I think ASEAN can be. But Indonesia is an example of the valuing of human rights, the valuing of political freedom under the last few presidents.

And I think that's, that's a lesson for everyone.

>> Arun Majumdar: Let me come to the US China relationship and US and China has had a long more than 100 year history, but the recent engagement, it sort of dates back to the ping pong diplomacy of President Nixon over here.

And that's in the 1970s. And it produced some remarkable shared prosperity and it drove waves of talent that we see around here and innovation in the United States. It shaped the diaspora, the communities out here. So if you go back in history, what do you think were the geopolitical forces or the events that were happening that actually.

And what are the implications in the broader world?

>> Condoleezza Rice: Well, you know, Arun, and I've talked to you about this, we had actually a very good relationship with China under Jiang Zemin, under Hu Jintao, we were able to work on some very difficult problems, including for instance, the North Korean nuclear problem, where China was for us the chair of what was called the six Party Talks.

So you had China, Japan, South Korea, North Korea, Russia and Japan. And so this was very effective. And I really do think we had a very good relationship. I will tell you that under Xi Jinping things have changed. And I'm not a believer in the Great man theory of history, all right, that some single person can change the shape of history.

But if I were a believer in the Great man theory of history, I would have to say that the rise of Xi Jinping has shaped a different kind of relationship with the United States. And it takes really three different elements. The first is we are the two. We and China, the two technological leaders in the world by far.

I mean, it's not even close for others. And I would have hoped that this could be a relationship of technological cooperation, but instead it has become a contest between the two countries for technological superiority. The technologies that we're talking about, AI and synthetic biology and robotics, these are transformational technologies.

My good friend Fei, Fei Li, who many of you know calls them civilizational, calls AI a civilizational technologies. This is serious business. And I've talked to many of my Chinese friends and I still have a number of friends in China, and I've said, why a speech that says that China is going to surpass the United States in frontier technologies, in quantum and in AI?

Why? Why give that speech? And then why have a policy which is called civil nuclear fusion that says that you're going to take civilian created technologies and make them available to the military and then have a policy under wolf warrior diplomacy that threatened your neighbors with territorial claims in the South China Sea, the East China Sea, not to mention, we talk about democracy.

There is a wonderful Asian democracy in Taiwan. Why threaten it with the kinds of military exercises and the like that we've seen? And it pains me to say this because I do believe the United States and China need to find a way to manage their relationship. Nobody wants conflict between China and the United States.

But I have to say those three moments, a speech challenging the United States on technological superiority, giving the view that that would become military technology, and finally, the policies that have created an Indo Pacific that is actually quite challenging and quite conflict oriented. That's a problem. And you've seen a reaction, by the way, not just from the United States, but you've seen a reaction from Japan, you've seen a reaction from Australia, you've seen a reaction from Vietnam, you've seen a reaction from the Philippines.

So when we talk about China's role in the Indo Pacific, it has threatened Asian allies as much as it has threatened the interests of the United States. And so I think that's a reality. And it's a reality that saddens me because I had such a good relationship with China before.

And I'll say one other thing. I would hope that what had been a growth engine in China will be recognized again, which was the private sector. These state owned enterprises in China are a drag on the Chinese economy. But the 10 cents of the world, the alibabas of the world, the baidus of the world, which are in the are among the best companies in the world.

If they could be allowed to have the impact on the Chinese economy that they once did, I think it would serve everybody well. And finally, I'd say it would be very good if Chinese citizens had more voice in their future. Many Asian Americans came to the United States because of our freedoms.

Freedoms are not a threat. They are an advantage to any country. And I would hope that the People's Republic of China would understand that.

>> Arun Majumdar: Well, I mean the US Is founded on the concepts of liberty and freedom.

>> Condoleezza Rice: Yes.

>> Arun Majumdar: And the openness. Right. And you mentioned contest.

Frankly, competition is not a bad thing. So where did this thing go wrong in terms of the competition? Contest competition. Maybe not contest. We were happy to compete, right? So what is it that the competition.

>> Condoleezza Rice: In fact, we helped to set up an international economy that was supposed to be competitive.

Remember that we believed that the international economy did not have to be zero sum, that if everybody found their place in it, the international economy would grow. That was a pretty radical concept after World War II. And let's remember the United States helped to rebuild its old adversaries.

So it's always been our view that a broad competitive environment is a good thing. China very much was welcomed into that in 2001. We were in office when China became a member of the wto. But there were certain expectations about protection of intellectual property. There were certain expectations about opening markets.

There were certain expectations about allowing foreign competition in. And many of those expectations were not met. And I think it has led to some concern about China's integration and particularly in the realm of technology. We will need to find a way to continue to have a relationship. But there are some things that need tending to, including the security environment in the Indo Pacific, which I think is currently quite challenging.

And I'm particularly worried that we see exercises in and around Taiwan that are quite threatening. Taiwan is no threat to the People's Republic of China. The People's Republic of China should not be a threat to Taiwan.

>> Arun Majumdar: So this is now often called the new Cold War. Well, you're a scholar of the Cold War.

Are there parables or are they totally different?

>> Condoleezza Rice: No, I don't like this. As a matter of fact, I wrote a piece in Foreign affairs saying stop talking about a new Cold War. It doesn't have the ideological fervor that the Cold War had under the Soviet Union, which basically believed that every country needed to look like the Soviet Union.

The Soviet Union was a military competitor, military giant, but it was not a technological or economic competitor for the United States. In no sense of the word. Do you know that at no time in its history was more than 1% of Soviet GDP accounted for in international trade.

That's how isolated the Soviet Union was. And it was isolated by choice. And so I think the parallel is not there. The thing we have to avoid that we were able to avoid during the Cold War is massive conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union. And there, I do think with China, we have some work to do.

One of the things that was reassuring during the Cold War was after the Cuban Missile Crisis, when we came close to having. In 1962, when we came close to having conflict, the two sides and Others began to think, you know, we really don't want to have an accidental nuclear war.

And Henry Kissinger and Richard Nixon worked closely with the Soviet Union to create a very detailed set, set of procedures, a detailed set of protocols, some transparency between the military systems that would not let an accident happen. Because with nuclear weapons you're on a very short time fuse.

Maybe a president would have 20 minutes to make a decision to end the world. Both the Soviet Union and the United States said, that doesn't sound like a very good idea. And so we don't want to have an accident. So I will tell you a story about exactly this.

On September 11th, when we were attacked, my first thought when I got to the bunker was, someone has to get in touch with President Putin because our forces are going to go up on alert. You do not want the Russian forces to start alerting too. So we alert, they alert, we alert, they alert.

And pretty soon you're at what's called DEFCON 1, which is a state of war. And so when I got to the bunker, President Bush, you will remember, was trying to get to a safe place. And President Putin was actually on the phone for President Bush. And so I took the call And I said, Mr. President, our forces are going up on alert.

And he said, yes, I can see that. And I thought, of course you can. You watch our forces all the time. But he said, ours are coming down. He said, we're canceling all exercises because we don't want there to be a mistake. Now think of that and contrast that to what happened to me as the national security advisor in 2001.

April of 2001. So just before 9 11, a Chinese plane, just hot dogging in international airspace hit our reconnaissance plane and knocked it to the ground for three days. Beijing did not take our phone call. Three days. I finally found my counterpart at a barbecue in Argentina. And I said to the Argentines, put him on the phone.

And I said, take our phone call. The President of the United States does not know the status of his crew. This is dangerous. Take our phone call. Now contrast those two. We need with China to have the same level of transparency, the same level of accident prevention. And so far we've had trouble getting Beijing to be interested in that.

The line has been, well, if we won't have an accident, if you stop doing what you're doing. Well, that's not a good answer. So I think that would be if President Trump and President Xi Jinping finally do meet. That would be very high on my list of subjects.

Let's get some, they're called deconfliction measures, so that our forces don't come into contact accidentally.

>> Arun Majumdar: Let's talk about the global economy. Someone described leading business thinker in China described the world economy as a Boeing triple seven and which has two engines and felt that one is the US the other is the United States the two biggest economies.

And when these engines run in harmony the world source and if the engines are pulling against each other it creates a lot of uncertainty. First of all let me ask you is this the right analogy and how could we get if so how could we get these engines to go together?

>> Condoleezza Rice: Well one reason that we advocated for China's admission to the World Trade Organization was the belief that this was a growing economy, very very talented and vibrant people. And that China would create its own bow wave of growth which would help the international economy to grow and I think for a while that actually was exactly what happened.

We're having, as I said, this technology competition conflict has cut off parts of that economy from ours and ours from theirs. I still think there is plenty of room for economic activity and trade in a whole host of areas. It's going to require both sides sitting down. President Trump is trying to get some of that done.

There are concerns about one thing that's happening in the Chinese economy. It's called, and economists will talk about, it's called the export of excess capacity. So if you're making more goods than your people consume, you export those, but that then cripples other economies. And so I do think that discussions about structurally how these economies relate to each other, not just what goods are we trading with each other, that, that come out of this particular period.

I have a lot of confidence in Secretary Besant. He has demonstrated the ability to understand these structural imbalances. And I think when we finally begin those discussions right now, I think the administration is focused on some of our allies and trying to make sure that we have trade relations there.

But I think the time will come, for those US China talks.

>> Arun Majumdar: Especially protecting the bond market.

>> Condoleezza Rice: Yes, yes, which is critical.

>> Arun Majumdar: Let me turn to Washington. And as we know, the American vision that Vannevar Bush set out in this endless frontier, you know, this was part of the American openness to bring in talent as we talked about the ideas and to trade, the openness to trade, et cetera.

And that principled framing of America is under fierce debate right now, as you know, in Washington. And the implications are tariffs on visas, which really affect a lot of people out here, foreign investments. And so the question I think we could ask and, and this is not just to China, but a lot of our allies.

So will America first also mean America alone?

>> Condoleezza Rice: Yeah, I don't think so. And look, it's early in the administration, and when it's early in an administration, you know that in our system a lot of people don't get confirmed. You have secretaries who are kind of home alone.

I think in time you will start to see it won't look like the old trading system. The President believes that the United States has been disadvantaged by certain elements of this trading system, and so he will look for structural remedies to that. So far, the mechanism has been tariffs.

But you've seen on and off about tariffs. You've seen, let's extend the time, let's negotiate. So I expect that you will see that over time we'll come to a system that looks more stable. The piece that is concerning to me is the Vannevar Bush as you mentioned it because the United States for 80 years has had a system that relied on universities to be the infrastructure for basic fundamental research.

For a short time we had Bell Labs, but when the baby Bells went away, it became a cost center. It went away. Many of those people escaped to universities to win Nobel prizes. And so I just hope that we protect scientific inquiry in universities. And I mean biomedical, I mean engineering, I mean across the board you can list the amazing innovations, whether it's the double helix or the discovery of stem cells or the transistor that became hp.

I mean there are just many, many, and we don't have a plan B. Universities are it. And there's a great thing about universities which is that unlike commercial activities which have to be driven by profit expectations, that's what boards want. I sit on corporate boards, that's what boards want.

But in a university a professor can get up and say, I, I wonder why that does that. And who knows what great discovery will come out of that. So I'm a huge believer in the role of research universities and not just the Stanfords and the MITs, but Purdue and the University of Alabama Birmingham and the biomedical side.

And so this has been something really great. And it has also benefited from the openness that you talk about because you want talent from around the world. I know that there is a lot of concern about what we do in a situation in which we have this rather more adversarial relationship with China.

But I've said it, and I've said it many again. I want to continue to have Chinese students in my classes. I want to continue to see you have them in your labs. I think it's good for us, I think it's good for them. And ultimately I think it will be good for free peoples everywhere if more people get to experience, experience freedom.

>> Arun Majumdar: So please feel free to line up. I'll just have a few more things. There's aunderstandably, there's some concern and anxiety amongst the Asian American citizens that this tension with China will spill over in how we treat our Asian American citizens. And we have a history with the Japanese Americans as well.

So in case that does. What do you think we should do now to preempt that to prevent it or mitigate it?

>> Condoleezza Rice: Well, I think working with government agencies, I spoke with Christopher Wray about this. They got off to a kind of bad foot initially with some of the initiatives that they have.

But I don't think anybody wants to repeat some of the darkest elements of our history. America has a self correcting mechanism and it's called democracy. And that self correcting mechanism comes in fora like these where the ASF can raise the issues, where people can come together to discuss the issues, where people can appeal to their congresspeople and say, look, this is happening.

Nobody should fear because of the color of their skin or their national origin. That's not American. And so it's not that people won't make mistakes, people will make mistakes, government will make mistakes, law enforcement will make mistakes. But we have to make sure that if those mistakes are made, that they are brought to the attention of those who can make sure that that mistake isn't made again.

And so, that's one of the great stories of America. Look, my ancestors were slaves and slave owners. I know something about the challenges. I don't see America through rose colored glasses, but I've been all over the world and there is no better place to be of a different skin color or of different national origin than the United States of America.

Because you have the voice and you can use it.

>> Arun Majumdar: One last question, and I hope it's not hypothetical. I hope it really happens. If President Xi and President Trump came to you independently or maybe together for your advice.

>> Condoleezza Rice: I haven't had a phone call from either one lately, but that's fine.

>> Arun Majumdar: That's why I said, I don't want it to be. I really want them to come to you. And to really chart a positive path forward, what would be your top three recommendations of what they should and should not do moving forward?

>> Condoleezza Rice: Well, one thing is going to happen, right?

In these encounters, everybody will list their grievances, they will. We listed our grievances. The others listed their grievances.

>> Arun Majumdar: That's how diplomacy happens.

>> Condoleezza Rice: That's what diplomacy is about. But I would say once you've listed your grievances, stop for a moment to listen. And when you listen, sometimes you hear what I call interest, overlap.

You hear something that might. You might both be interested in, and maybe it's just something small, but then you can move out from there. And I would start with the one that I mentioned before. I don't think either President Trump or President Xi Jinping want to have a military confrontation or military accident.

They just don't. So let's start by talking about how we would avoid that. Your area, which is climate, you know, we have some work to do to make sure that we're giving the planet the very best chance. Could we talk about how we might go about that? And so I would try to have two or three things where we can just have a conversation, not proposals, just a conversation about my concerns, your concerns, my fears, your fears, my hopes, your hopes.

And let's see if we can find just a few steps for forward for this relationship. And I would say to President Xi, and again, I had the best of relationships with President Jiang Zemin and particularly President Hu Jintao. When you threaten another country, particularly a democracy like Taiwan, it's not a good look for a country of your size.

And so could we at least back off and let the Taiwanese people have peace?

>> Arun Majumdar: Great, let's move to quench.

>> Arun Majumdar: We only have a few minutes, but let me go to this microphone first. Quick, short question.

>> Speaker 4: Yes, thank you, Secretary Rice and Dr. Majumdar. And I really liked what you said about the great American experiment being sustained by us all having voices and having the ability to use them.

So, as a high school student, as the next generation, where do you see the youth participating in civic engagement, especially bridging issues in our polarized world, both within the country and with our partners?

>> Condoleezza Rice: Thank you so much for that question. And I would say you can start now with civic engagement.

And I would give you three ways to be civically engaged. The first is find a friend who disagrees with you about something and sit down and have a civil conversation with them where you're actually listening, right?

>> Condoleezza Rice: Because we have a tendency to go to our own corners.

And social media, I even do social media. All right, so I'm not a Neanderthal, but social media leads you to only talk to people who think like you think. So be sure you're not doing that. The second thing is try and engage in some activity. Maybe it's even a local political race of some kind.

You know, some of the problems that were being found in San Francisco around attacks on older Asian Americans. It really got the attention of mayors and police chiefs. So sometimes we think engagement in Washington, sometimes it's engagement at the local level that can help most. Then the third thing that I would say is, go work at a boys and girls club if you really want to be inspired.

>> Glenn Tiffert: those kids are overcoming things that none of us would have even dreamed of overcoming.

>> Arun Majumdar: And it really will help you to recognize how much you have. So those are my three ways to engage.

>> Speaker 4: Thank you, Secretary.

>> Arun Majumdar: There's so many people. Let's actually have the questions, short questions.

First over there. Next over here. The young lady out there, and the one over there will have four microphone, but three of them. Let's get the questions quickly, and then we'll.

>> Speaker 5: Secretary Rice, do you worry that US Might lose its moral leadership, you know, telling other people country what to do as they try to make Canada the 51st days and buying Greenland and all this stuff?

>> Arun Majumdar: Okay, and then question over here.

>> Speaker 6: Secretary Rice, I was wondering, what do you think that people could do to make the public perception of universities better? Because I think in Gallup polls, like, the confidence rate in universities has fell nearly 20% over the past decade.

>> Condoleezza Rice: Yes, thank you.

>> Speaker 7: Hi, Secretary Rice, My question is, given the current anti Asian sentiment in the US, what advice would you offer to young Asian American leaders who want to pursue leadership roles in this environment?

>> Condoleezza Rice: Thank you. I'm not worried about Canada. I think Canada should be just fine.

>> Condoleezza Rice: The only thing I was sorry for Canada, I'm a huge hockey fan. I wanted them to finally win another Stanley cup, and they didn't. But no, look, it was an unfortunate thing to be said. I think we've kind of gotten past that. And what we need to do is recognize how extraordinary we are, how extraordinarily lucky we are to have Canada and Mexico as neighbors and the work that we can do together economically and politically.

And yes, in terms of control of immigration. So I Hope that that's the next chapter in U.S. canada relations. I have a lot of respect for Canada, a lot of love for that country when it comes to universities. You are so right. Look, universities have a lot to answer for.

All right, I'm just gonna say it. I believe, as you know, in scientific research. But is that really what people see when they see universities? Or do they see places where sometimes the leadership seems determined to speak about every social issue, whether they know anything about it or not?

Do they seem to be places where if you have views that are not popular, you can't even say them in the classroom because you might be doxxed or you might be put on social media? Do they see places where you don't have a range of views, but it looks like you have an orthodoxy to which the university is.

And do they see in certain cases that we talk about things like marginalized people as if only the color of your skin makes you marginalized as opposed to maybe your circumstances are different? I will tell you something. I'm not even the first PhD in my family. My aunt was a PhD in Victorian literature.

She wrote books on Dickens. You think what I do is weird for a black person? She wrote books on Dickens, for goodness sakes. All right, so you look at me and am I uncomfortable on a college campus despite the color of my skin? No. My parents and I used to visit college campuses like most people visited national parks.

We went 100 miles out of the way to see Ohio State. So don't judge me and what I need by the color of my skin. Universities have been too much that way and we're paying for it. So I think that we have to remind people too that we're not just elite.

20% of Stanford students are first generation students. Could we say more about that? Because we want to be a place where the best and brightest, regardless of circumstances, can come. And we are trying to do things at Stanford to make sure that our students listen to each other and that we can debate even the hardest issues in a civil way.

And, and I think if we get back to what we really do, which is to do great research, do great teaching, and from that our role in creating leaders and great policy, that's our sweet spot. And if we get back to it, I think people will start to respect us for what we do.

I think they've lost sight of what it is we do. And thank you for that question.

>> Condoleezza Rice: I'd be a little bit careful of branding the entire country as anti anything. So again, as I said, I grew up in the segregated south in Birmingham, Alabama. And even in the segregated south in Birmingham, Alabama there were an awful lot of very good citizens who just wanted to live together.

And so I think your activism, your ability to work through organizations like this, your ability to call to the attention when there are injustices, those are all extremely important things to do. But it's also really important not to brand all of your citizens, all of your fellow citizens as somehow racist.

That won't get you anywhere. Most Americans want to live in peace and harmony. Most Americans will accept you for who you are. And if you can start with that and, and then work on the problems, I think it will be a much more effective strategy for all.

>> Arun Majumdar: This could go on for a long time.

But thank you for your words of wisdom. This has been such a treat. I really appreciate you coming here. Let's give Condi a big.

ABOUT THE SPEAKERS

Secretary Condoleezza Rice is the Tad and Dianne Taube Director of the Hoover Institution and the Thomas and Barbara Stephenson Senior Fellow on Public Policy. She is the Denning Professor in Global Business and the Economy at the Stanford Graduate School of Business. In addition, she is a founding partner of Rice, Hadley, Gates & Manuel LLC, an international strategic consulting firm. From January 2005 to January 2009, Rice served as the 66th Secretary of State of the United States, the second woman and first black woman to hold the post. Rice also served as President George W. Bush’s Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs (National Security Advisor) from January 2001 to January 2005, the first woman to hold the position.

Arun Majumdar is the inaugural Dean of the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability. He is the Jay Precourt Provostial Chair Professor at Stanford University, a faculty member of the Departments of Mechanical Engineering and Energy Science and Engineering, a Senior Fellow and former Director of the Precourt Institute for Energy and Senior Fellow (by courtesy) of the Hoover Institution. He is also on faculty in the Department of Photon Science at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

Glenn Tiffert is a distinguished research fellow at the Hoover Institution and a historian of modern China. He co-chairs Hoover’s program on the US, China, and the World, and also leads Stanford’s participation in the National Science Foundation’s SECURE program, a $67 million effort authorized by the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 to enhance the security and integrity of the US research enterprise. He works extensively on the security and integrity of ecosystems of knowledge, particularly academic, corporate, and government research; science and technology policy; and malign foreign interference.