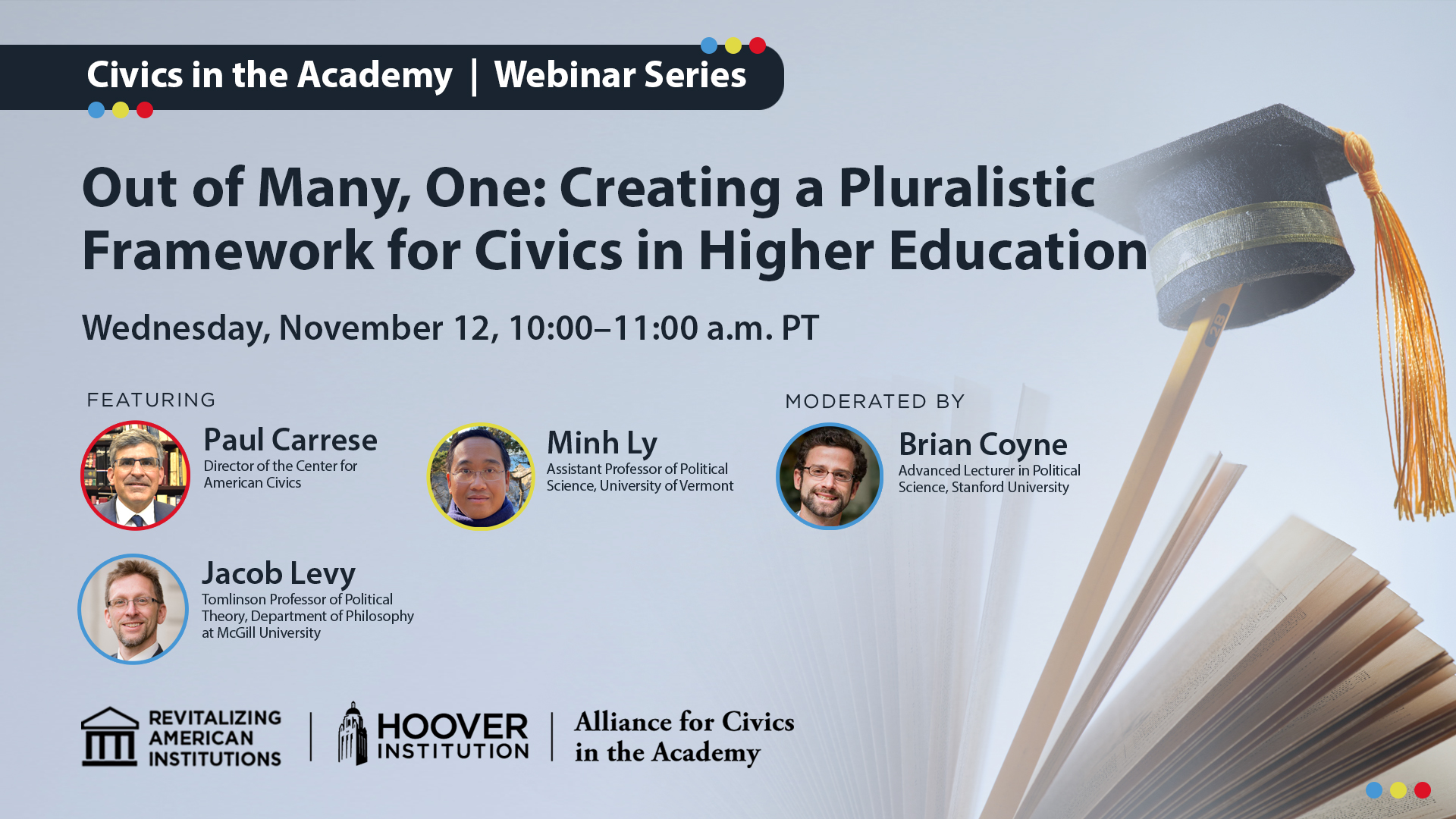

The Alliance for Civics in the Academy hosted "Out of Many, One: Creating a Pluralistic Framework for Civics in Higher Education" with Paul Carrese, Jacob Levy, Minh Ly, and Brian Coyne on November 12, 2025, from 9:00-10:00 a.m. PT.

With increasing cross-partisan support for renewing civic learning in higher education, an important question emerges: how can colleges and universities create a framework for civic education that cultivates shared democratic values while honoring pluralism and diverse perspectives? This webinar explores this challenge in depth, highlighting guiding principles and exemplary approaches for creating a shared vision of civic education suited to a pluralistic society.

- Good morning everyone. My name is Brian Coyne, and it's my great pleasure to welcome all of you here to, for Many one, creating a pluralistic framework for civics in higher education. The second webinar in the Alliance for Civics in the Academy's webinar series. Thank you so much for joining us here. I want to take a moment to introduce myself and our distinguished panelists, and then we will get going. As I said, my name is Brian Coyne. I'm an advanced lecturer in political science here at Stanford University. I'm also the associate director of the Stanford Civics Initiative and the course manager for Stanford's own civics program, college 1 0 2 Citizenship in the 21st century. But of course, we're here today with our three distinguished guests. We have with us First Professor Paul Carrese, who's director of the Center for American Civics and Professor in the School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership at Arizona State University. He served as the school's founding director starting from from 2016 to 2023, but formerly he was a professor at the United States Air Force Academy co-founding its honors program, which blended liberal arts and leadership education, professor Carrese teaches and publishes on the American founding American Constitutional and Political Thought, civic Education, and American Grand Strategy. His forthcoming book, may of 2026, is Teaching America Reflective Patriotism in Schools, college and Culture. Of course, very relevant to our topic today. Paul, thank you so much for joining us here, introduce our second panelist, professor Jacob T. Levy, who is the Tomlinson professor of political theory and associated faculty in the department of Philosophy at McGill University. He's the founder and coordinator of McGill's Research Group on constitutional studies whose Charles Taylor Student Fellowship is devoted to an intensive non-credit year long reading group of major works in the history of political, moral, and social thought. Jacob, thank you so much for being here. Really looking forward to have you here, having you here, and I'll note that you make this an international panel by joining us from Canada. We also have with us today Professor Minh Ly, who is assistant professor of Political Science at the University of Vermont. His book answering to us Why Democracy Demands Accountability will be published by Princeton University Press in March of the coming year. Professor Ly's research and teaching focus on democratic theory, the rights and responsibilities of democratic citizenship, economic justice, global justice, and civic education. It's work has been published in the Journal of Politics, the European Journal of Political Theory, the Review of International Political Economy and other Journals. Before joining UVM, he was a lecturer at Stanford University. We were sorry to lose you in and also a postdoc at Princeton. And thank you so much for being here. Thank you to to all of our panelists, and once again, thank you to all of our attendees. We are gonna spend the first th roughly 35 minutes in conversation among ourselves. I'll ask some questions that will give our panelists a chance to speak about the challenging issues of pluralism in civic education that we face today in our, our last 20 minutes. Members of the audience will have a chance to pose questions directly to the panelists, so have those, those comments, those questions at the ready for the end of our session today. Okay. So Paul, Jacob Min, I wanna start with just a a a simple introductory question that I think can get our conversation going here. Our theme for the day is pluralism. And I think a, a standard definition of pluralism that we can use here has both an empirical and a normative component. The empirical component is that just as a fact, any group of students or faculty or citizens for that matter, are just going to have a diversity of political, social, cultural, philosophical, religious commitments. So that's the, the, the empirical side of it. But then there's also a, a, a normative commitment to valuing, not just tolerating this diversity of views. And I think this is sort of what distinguishes pluralism from what you could call mere toleration. So as a starting point, I wonder what what you would say you see as the role of this form of pluralism, both the, the empirical and normative sides in civic education. Let's see. Paul, you're already unmuted. Why don't we start with you? Thank

- You, Brian. Thanks to the alliance for Associ, the Academy, Hoover Institution Stanford for organizing these webinars. I'll start with a thought that the American Constitutional order embraces all of these concepts of pluralism, the, the empirical and the normative. Our webinar title is the English translation of the phrase from the American founding era, pluribus unum. And that in one sense meant former colonies. Now states forging a union, but it was always understood in both these empirical and normative senses. Free people will have a diversity of views and the, the American colonies on the Atlantic seaboard from north to south were diverse in a a, a certain set of ways. We've only become more diverse over 250 years or, or 400 years, whichever way we wanna count it. So I think if we focus on American constitutionalism as a core topic of an American civic education, we we're in better shape to think about the empirical and the normative dimensions of pluralism. How a constitutional structure helps to organize disagreement and, and make disagreement more constructive, never to do away with disagreement, right? But, but to make it more constructive with a diverse, plural and increasingly plural set of local governments, state governments, peoples groups, et cetera.

- Okay, I'm, I I would like to start with the disclaimer that I've never taught civics and I have questions and concerns about the enterprise, which we might have a chance to talk about. So my answer is gonna be partly in the spirit of here are things about a civics education that I, I could imagine being relevant to pluralism and vice versa, but without firsthand classroom experience with them. So one is to teach students the skills and the civic virtues about management of living with possibly embracing the nonpolitical aspects of pluralism. So, for example, teaching students about coexistence with people who have different religious beliefs, which I do take it to be a key feature of, as Paul was saying, the American constitutional order or that of other liberal democratic constitutional regimes. I don't quite know how one teaches that virtue if students are coming in predisposed against it, but it does seem to me like a worthy goal. Likewise, teaching how to coexist among in, in conditions of cultural pluralism or racial pluralism. Those seem like worthy goals. Now, in both those cases, that's going to involve a kind of monistic substantive equipment on the part of the syllabus, the curriculum, the instructor, the program. And this, that's one of my questions and concerns about explicitly civic education, Is what it's like to say, right, in order to teach you to be plurals, we will teach you to be say, good liberals, and that will be experienced as non pluralistic. In the second sentence that I want to talk about, which is political pluralism, living together in a liberal contestatory democracy also includes coexistence with people of different political views. And one thing that you can do in a civics class, one thing that I think is traditionally done in civic classes is teach stuff about democratic procedures and to teach commitments to rules about how it is one has peaceful coexistence, peaceful contestation for power and peaceful management of political and partisan and ideological differences. There are question marks about that in a university setting, because a commitment to political non orthodoxy is a central fact about universities, not just as a creation of the US tax code that says universities must be nonpartisan in order to maintain their tax exempt status, but as a substantive commitment of academic freedom that universities must not embrace and must not teach a political orthodoxy. We read about this in vapor's sciences vocation from a hundred years ago, and I think that he had the core elements of it, right? I think there's a trade off or a risk of attention between a civics education about the first kind of pluralism. Let's teach people to be religiously tolerant. Let's teach people to embrace multiculturalism and social life. And the pluralistic piece in the second sense, which is ensuring that the curriculum is open to, in a non-Orthodox way, students coming from a variety of political perspectives, insofar as a civics education is not just teaching the substantive correctness of say, liberalism or multiculturalism, then it's not clear how it's going to address the first, but if it does teach those items of substantive correctness, then it's going to run afoul of non orthodoxy and is going to create real strain intention about the pluralistic openness of the classroom. Those are some of my questions and concern that,

- Thank you, Jacob. And, and you know, I, I appreciate you raising those right at the start here. 'cause those I think just are the questions of teaching pluralism today in 2025, as we'll talk about in a bit. I think there was a, there was an answer to all of this decades ago that, that I think we do need to, to rethink today. So thank you for that. Min let's go to you to start us off.

- Well, Brian, you've talked very importantly about two aspects of pluralism. The first is the empirical aspect, and the second is the normative aspect. So the empirical aspect is important because one obstacle for students acknowledging the importance of civil disagreement is this preconception that everyone agrees with them, right? So something that I display at the very start of class is that if you look at party identification from the Gallup poll from 2024, you have 28% of people who identify as Democrats, 28%, same percentage that identify as Republicans. And then 43% of people who identify as independents. It's been increasing the people who identify as independents since the early two thousands. So no matter what side they happen to be in Republican, democrat, or independent. They don't represent a majority of people. The majority of people actually disagree with them. So the first thing to get students to talk about through difference is to make them realize that a lot of people disagree with them, and that they're gonna have to get along with people who disagree with them in a pluralistic society, as Jacob was mentioning. But then the second aspect of pluralism you mentioned was a normative aspect. Why should we not simply begrudgingly tolerate the fact that other people disagree with us, but actually welcome it despite the fact that disagreement can sometimes be uncomfortable? I want to talk about two moral aspects of pluralism. The first is the epistemic dimension that we'll actually make better decisions as a democracy if we talk with people who disagree with us and morally debate and deliberate. And it's an idea going back to John Stewart Mill and it's idea of EPIs, what's called epistemic democracy, where epistemic comes in the ancient Greek meaning knowledge. So when you have a diverse group of people who debate with one another, you'll come to better decisions. And when you artificially enforce a consensus or orthodoxy, as we saw in the Vietnam War, it can lead to disastrous decision making. And Robert McNamara, who was Secretary of Defense during President Johnson's and President Kennedy's administrations admitted that a root cause of the disaster of the Vietnam War was enforcing an artificial orthodoxy or consensus behind the war. So people will make better decisions if they deliberate across difference. But then the second moral commitment behind pluralism is this idea of civic friendship, which Paul has written about, along with Danielle Allen, who's a classist, and Peter Levin as well in the Educating for America American democracy report. So civic friendship is this idea that we should receive each other as friends. It goes back to the ancient Greek verb, a goin to receive with friendship to welcome openly and importantly to protect greatly. And we orient our each other as friends when we listen respectfully to one another, rather than to to shut out debate, to refuse to listen to others, acknowledge other people's dignity. So I think part of acknowledging pluralism is that foundation of a gap, end of civic friendship that we regard each other with.

- Thank you so much, man. It's really helpful to have that, that deep background as, as a foundation for our conversation here. So the, the next question that, that I wanna pose here picks up on a, on attention that, that Jacob pointed us to a few minutes ago, that plural pluralism in education, we've talked about it does presuppose again, both, both as a fact and as something we value a wide difference of opinion. But Jacob also pushed us to consider the fact that there are specific values embedded in I think any plausible version of civic education. Democracy as a procedure is a certain set of values that, you know, I, I think are right, but are, are, are not universally shared. And I said before that there was, there was an old way of dealing with this tension. And the old way was to say, well, everyone agrees on democracy. And so therefore if we, if our education presupposes democracy, if our education is oriented toward democracy, yeah, those are specific values, but everyone shares them. So there's no problem of pluralism there. I, I think as, as a, as a factual matter, we, we need to think hard about that. In, in 2025 and pupil poll from last year, 32% of Americans agreed with the statement that rule by a strong leader or the military would be a good way to govern their country. We see, you know, similar results in, in other countries as well. And so the, the question that, that I, I'd like to pose for everyone here is if civic education moves the needle on that number, is that on its own evidence of a failure of pluralism because civic education is having an effect on people's views, presumably also their, their partisan views. Should we aim to not have an effect on that? Or do we kind of own that we have specific what Jacob called monistic values and at the risk of, of some tension with other forms of, of pluralism? Let's see, Jacob, do, do you wanna have thoughts on this?

- Sure. Simply having a measurable outcome Doesn't show that something illegitimate has happened. I suspect that a liberal education, an education oriented around the shaping and opening of minds, which is different from a civic education, I suspect that a liberal education also moves the needle on that. That is, say I suspect people who have a liberal arts education at a university that is good at that kind of thing or college is good at that kind of thing, have a different set of answers, would not poll so high on the strong leader. Now, if that's right, if a liberal education moves the needle, even though it is not the purpose of it to move the needle, then I'd wanna ask the question, do we have strong reason to think that a civics education, a an explicitly intentionally didactic civics education would move the needle more as well as asking the question about the legitimacy of doing so. But, but the difficulty of 2025 isn't just democracy or not democracy, because as soon as you start spelling out substantive democratic commitments in 2025, for example, a really central aspect of a democracy that political scientists love to talk about, which is that losing parties peacefully concede in 2025 saying that is going to be heard correctly By a lot of students as embracing a partisan position. Yeah, exactly. 'cause it has now become a matter of partisan contestation, whether both parties are supposed to peacefully abide by the results of an election. And you'll get people who in answer to that poll would've said, yes, I embraced democracy. But when you push a little bit on that equipment, you'd find that they do not, for example, have a strong sustained equipment to losing parties peacefully seating at the end. So I I, I think that it's a little bit of a straw man to say, would it be bad if there were an effect? The concern has to be about a kind of non neutrality of intent, not non neutrality of effect, because liberal education in general will have a non neutrality of political outcomes. We justify it by saying, well, we're not teaching students what to think. We are teaching them something about how to think. And it will turn out that certain styles of thought are less compatible with certain kinds of, for example, really simplistic political conclusions. Like what we want is a, a strong great man to tell us what to do.

- Thank you, Jacob. I'll, I'll just add that it, it may sound like a strong man, but the, the question was in part inspired by another panel that I moderated last week, in which some of the panelists argued essentially that the fact that liberal education does move the needle and civic education does move it even more, is the reason for the decline in trust in universities that we also see in polls. And, and panelists argued that that is, that we should strive to, to correct that perception that our education has kind of measurable effects students political and, and partisan commitments.

- I mean, it does have it, it has, has a lot less than, than the popular press tend as the, the predictors of an adult's pol politics still are overwhelmingly driven by background demographic facts, like where they're from and what religion they are, and what race they are and what sex they are. They're very, very little shaped by what happens in the classroom by deliberate decisions from their professors. They're shaped a little bit by the climate among other students. I worry that the shift from the liberal to the civic deprives us, us as universities of professors of the true defense, which is, well, maybe your students change their minds about some things at university, but it wasn't because we were trying to make them do so.

- Hmm. Paul, you wanted to get in? Yeah, I wanna jump in to suggest that Jacob's view about the principle of non orthodoxy being the one principle of higher education. And the one principle of liberal education, I think misunderstands the history of American higher education, I'll just put it that way, private to, to public. You couldn't possibly have public universities starting with University of North Carolina in 1789 unless there was an effort to understand and negotiate a tension between the civic education mission, the public civic education mission of a public university and the liberal arts dimension. At the time, there wasn't such a thing as a university per se. So there, there's an inescapable set of tensions were gonna have here, right? The one orthodoxy of a university as the principal of non orthodoxy can't, can't have any civic citizenship education role there. There are tensions everywhere. An earlier model of the American university, which we've largely lost over the past 75 years. I is in investigated in the, the book by the president of Ron, president of Johns Hopkins University, Ron Daniels, right? The first research university in America. That book from 2021 is what Universities owe Democracy. And Daniels makes the argument sitting atop of research university, all research universities, all private universities, all public universities, all of American higher education owes a citizenship education to every graduate. That's what we, the higher education sector owe to democracy is his broad term, I would say more specifically to America's constitutional order. And he makes a, he and his two co-authors make quite articulate argument there. Yes, there are tensions between a civic education and a liberal education, but the statement of principles from the, from the Alliance for civics in the academy, very elegantly embraces that tension. There are clearly liberal education principles in this statement, and there are civic education principles held together partly in, in both halves of this, the liberal education side, you educate about tensions and paradoxes and, and, and how to hold complex sets of ideas together. But as I mentioned earlier, this is also a civic education for the American constitutional order, federalism, separation of powers, freedom of speech. These are all about holding tensions and holding principles together. So I, Jacob and I just, you know, dis disagree about what the, the a CA principles mean for holding together the tension between liberal education and civic education.

- Thank you, Paul. It's helpful for us to have pluralism even even here on this zoom min, please.

- Oh, so Brian, you were raising the concern that if a civic education has an impact on people's beliefs in moves the needle that we might worry about, its its bias. But I think, you know, one thing to think about is the fact that all forms of education will have some impact on people's belief. If you teach people about the germ theory of disease, they'll start washing their hands and being more careful about food safety, for example. So then that raises the question, if a civic education's gonna move the needle, in what ways should we be concerned if there is a kind of bias? And we certainly would not wanna have a civic education that would be partisan, where people feel that they would have to be a progressive or conservative in order to do well in the class. So we would definitely wanna avoid that partisanship. And in the class we would also want to inculcate a certain set of skills where people would be able to think critically about different views and understand views that differ from their own, including views about democracy. So for example, when I teach introduction to political theory, I teach, in addition to people who are defenders of democracy, I teach people who are critical of democracy as well. So students need to be familiar with both sides of the argument. They need to be equipped with the skills in order to understand multiple perspectives and not their own. And they need to know that the civic education is not about hewing to a party line, but about acquiring a certain set of faculties where they can understand people who disagree with one another and to critically think about what they're doing. And interestingly, and this builds on a statistic that Paul mentioned in the Educating for American democracy report. Americans were pulled a, a series of demo potential democratic reforms, such as changes to our election system, for instance. And the one reform that commanded a bipartisan consensus was increasing funding for civic education. So I think there's a, a widespread acknowledgement when the majority of Americans can't name all the civil rights protected in the First Amendment that we're in pretty bad shape, and people need to know more about the f foundational principles of democracy.

- Sure. But, but min, just just to follow up on that, so, so you said that that all education changes beliefs, surely that's true. Maybe, maybe even my student who falls asleep in the back row a little bit gets in and changes their beliefs about something. Surely that's true. I I just wanna push on when you said that education in general and civic education should not be partisan again. Sure. Surely true. But from the comments that that have come up before, I think it's become clear that in the current climate, some of the belief changes that any plausible kinda education we might do might have specifically partisan ramifications. Right. So Jacob was alluding to the fact that after the 2020 election, the Republican party, by and large, did not peacefully concede that, that their candidate was defeated in the election. A lesson about peacefully conceding in elections may very well cause some students to change which party they support. Is that, is that, is that a tension in, you know, your, your answer there between accepting that beliefs will change and not wanting to be partisan?

- Yeah, I think that if we're teaching about democracy

- And

- We teach that there are certain benefits to democracy, there might be a certain partisan valence to the overall shift in opinion. But as Jacob mentioned earlier, the important thing is for it not to be intentional that teachers shouldn't be going into a civic education class thinking, well, the purpose of holding this class is to get people to be good democrats or good publican publicans. But to really think carefully about, you know, to understand first of all, why are some people opposed to democracy? Why are some people opposed to the peaceful transfer of power?

- Yeah. - So being able to articulate exactly why some people hold that view and in order to critically examine that view as well as their own, I think is what civic education would aim at. Because inevitably we're gonna have to work together as co citizens in a democracy. So if we're only capable of governing ourselves, if we're able to have a, a conversation with one another and to come to decisions, I mean, the alternative is the, the rule of a strong person, right? If we can't have a, a civil dialogue with one another.

- Alright, thank you. And I'll, I'll just note that our, our colleagues who, who teach on international law and the, and the rules of war will know that the foreseeable, but unintentional effect is a, is an important but, but sometimes slippery concept. Paul, you, you unmuted? Did you wanna speak on this?

- No, I, I appreciate the, the, the pluralism and the disagreement we have here. I think it partly shows that the, the folks interested in the alliance for civics in the academy can hold differing views and wanna be Socratic or liberal arts minded in talking with each other about these questions. But I, I do think one point to reiterate, because it's now the very clearly the, the minority view among professors across a range of disciplines in higher education, who, who might think they have some relation to civics, that we would do a better job both in liberal education and in civic education. If in American higher education, we taught about the American constitutional order in Canadian higher education, teach about the Canadian constitutional order because the complexity and the pluralism built into these constitutional orders, right? They're not democracies, they're, they're liberal, constitutional, democratic republics and, and sorting through all of that, getting republic what now

- Canada is not

- A republic. So in, in, in the American scheme, right? Liberal, constitutional democratic republic to sort through all of the history and the, the empirical reality and the, the history of debate about all that is a liberal arts education in, in a classroom. And the conversations and learning it sets up beyond, beyond a, a classroom while also being a civic education that in the American sense is not an indoctrination. It's, it's a common understanding about some very broad principles and some very broad rules like what you do when you lose an election. But, but with, you know, providing the right balance between freedom and order, which by the way, university needs and a classroom needs and, and then universities prosper because you've got ordered liberty in, in the broader democratic republic.

- So in a, in a moment, I, I'd love to transition to a question that invites each of you to bring in some of the, of your expertise from your own universities. I know this is a moment of sort of experimentation about civic education here at Stanford. Our, our college program is still relatively new. We are, we are iterating it. And I, I'd love to hear from each of you about how your universities are handling civic education. And I know, Jacob, you mentioned you haven't done it, but perhaps that you can still share about the approach at McGill or, or in Canada more generally. So, let's see, min, I, I know you've been involved in your, your university's efforts on this. Do you wanna share what's going well at University of Vermont? What perhaps folks at other universities could, could take from your experience there?

- Sure. What we're doing really well is that we have a global citizenship, a GC two requirement that every student has to take throughout the university, whether they're majoring in nursing or business or the College of Arts and Sciences where I teach. So that's very helpful because about 90% of the students who take my introduction to political theory course are not political science majors. So I think it's important to engage and citizenship in the 21st century at Stanford recognizes it. It's important for people who are not political science majors also to engage in these questions of citizenship because people who are engineers, nurses and doctors are also gonna be important. Member farmers are gonna be important members of our democracy. The disadvantage though, with how we're approaching things is that the global citizenship requirement can be satisfied by an extremely broad array of courses. So courses that have nothing to do with a discussion plausibly about citizenship, although they have a lot of intrinsic interest in them. So having something like the Stanford model where every freshman has to take a course in citizenship, I think would be very helpful. We're starting to pioneer that because in the honors college I've been involved in a process with Dean Gentleman just started civic engagement minor. So a lot of people who are in the Honors College who are, again, not political science students are starting to take this. So if it's successful in the Honors college, we might potentially think about scaling it up to more students at the university. But we're also very proud of the work that we're doing in terms of introducing students to democracy and practice. So one of my colleagues, Jack Rasinski, he's a professor at the University of Vermont, has a Vermont Legislative Research Service. So a lot of students are actually conducting research for state legislators and the Vermont State Assembly. It helps to promote a kind of rough, a kind of alliance between universities and state legislatures when you see that we're actually producing policy relevant research for them at their request by commission from them. And also, we have a great program called The Center for Community News, where students are trained to report on environmental news and news about their local communities through the Center for Community News. That is, and there's some fantastic work being done over there by Dr. Richard Watts and Meg O'Reilly. So we're very happy with what we're doing there as well.

- Fantastic. Thank you. Jacob. I wonder if, if you'd share how McGill is approaching this sort of curriculum, you know, is is it different in a different national context, you know, than, than what we've heard from Paul and Min.

- So I, I don't think that we have anything at McGill that would count as a civics curriculum. Certainly nothing as part of formal coursework, neither in the faculty of liberal arts, nor in the university as a whole. And certainly, certainly nothing that is mandatory and shared across all students to do so in our context would be extremely complicated, partly for pluralistic reasons. And here I'll note a couple of things about our student body. One is our student body is a, about a third international and orienting a curriculum around teaching the values and virtues and meanings of the Canadian constitutional monarchical order would seem like a funny thing to do. Now, sometimes in my classes, what I'm teaching about constitutional systems, I do try to draw some of the American students out a little bit.

- Hmm. The - Extent that Americans have grown up in an anti monarchical political culture, and to get them to see the point and the value of some of the Canadian practices. But in addition to the international context, there's the fact that we are an anglophone university inside Quebec. McGill has a strong tradition as being an institution that is very tied to the existence of the overall Canadian Federation. But the public university system is provincial. That is in his strong sense. We work for the province of Quebec.

- Hmm. - Our institution is called the Royal Institute for the Advancement of Learning in, in another sense, we work for the monarchy, but we work for the monarchy of Quebec. And if we were to engage in deliberate didactic education in the values and virtues of the continuing existence of the Canadian Federation, that would be immediately picked up on by the province as an illegitimate meddling in the politics of the province. Because we do have a substantial share of, of students from Quebec, and not only anglophone students, but francophone students from Quebec. If we were in the business of trying to teach the Francophone students from Quebec that they should not advocate independence and sovereignty, then the, the province would be outraged.

- Thank you, Paul. Let's hear from you and then we'll go to questions from our audience.

- Yeah, thank you. I'm here representing, in a sense, the public university renewal movement of the past decade emphasizing civic education. It started at, in the state of Arizona in 2016, with a mandate from the state government to establish a new unit at Arizona State University, a department sized entity. Nine years later, this is now in 12 states total on 17 public university campuses that either state legislature and governor or a board of regents over a university system has mandated that a public university have a new unit at, in two of the campuses at their colleges, quite explicitly with deans, most of them are, are department sized entities or centers, but with a little bit more of autonomy and wherewithal than most centers have, so that they can at least push for faculty hiring tenure line positions 'cause they have the funding for it and, and even a center having its own minor and, and other kinds of academic programming. So here at Arizona State University, we built a department, has a big long name School of Civic and economic thought leadership with three missions to first academic mission blend, liberal arts education, and American civic education, all the ways that departments do that. Courses, minor's, degrees, majors, we have an MA degree as well. Second mission to have some practice of the civic virtues by having a public speakers program, the Civic Discourse Project. So we're reaching the Arizona State University community and then the broader Arizona and even national community. We partner with Arizona PBS to have all of those speaker events put up on PBS website and, and on our YouTube page. And some of them are dialogue debate events. Some of them are single speaker events. Third mission to work with teachers who are in K 12 schools about improving their capacity for American civic education. So those three missions, one of the things that was happening in parallel, but also happening in part because of this renewal effort to have new units established is state governments or state boards of regents renewing American civic education requirements in public universities. So Arizona's Board of Regents established an American civics requirement for all the public university students after our civics department was established. Other states have done it differently. So this is now a topic of discussion in the American Political Science Association, what to do with these new state requirements. Some of them have been around for a very long time. Texas had their, basically their American civics requirements since the Cold War, since the 1950s. But, but several states have added them just in the past decade. So it's an in, it's an interesting landscape. And then just one final thought, the, the Stanford Civics initiative, Brian, that you're so deeply involved with is an example of a parallel effort in an elite private university to address the civic education mission in its founding documents in the Stanford founding grant. But this has happened at Johns Hopkins University to some degree. There's now a Yale Center for Civic thought. It's been established, and I was just at a two day seminar at Harvard Private Seminar, but a set of senior faculty at Harvard talking about civic thought as some kind of a curricular innovation or or intervention at, at Harvard. So there's a private university renewal of interest in the civic education mission of American higher education.

- Right. Fantastic. So with, with my eye on the clock here, I'm gonna suggest that we move into the portion of our event where we take questions from the audience. Once again, for, for folks out there, you can put these into the, the question box. And we will ask as many of these as, as we have time for the first one, throw it out there and then maybe I'll leave it open to, to each of you, which of you would would like to jump in on this? What if we don't frame the question as liberal or civic education, but rather in terms of critical thinking? And I, I take the question to be asking, would that solve some of the issues of the limits of pluralism that we were discussing before if we focused on critical thinking as a, as a shareable skill?

- I, I'll repeat the, the, the basic theme I suggested earlier on our pluralism theme, that there's a kind of an American answer, which is when you, when you're, you know, posed some opposition, the American answer is yes. Right? The American answer is both end. This is, you know, I think it's partly Montesquieu and the American framers educated in a liberal education, but also in montesquieu politics, embrace complexity rather than try and reduce complexity to your one big idea and, and enforce reality to, to behave according to your one big idea. So both in politics and in academic liberal arts spirit, I think it's better to stick with the complexity and the tension, say in a, in a constitutional democratic republic, the principle of pluralism is, is not a problem. It's a, it's a good reality. It be managed. This has an educational component to it, which is gonna have complexities and tensions, the liberal art education, liberal arts tension with the, the civic education tension. So coming up with abstract terms like democracy or like critical thinking or like civic engagement, I think in we've tried this for 75 years and we are not in a better shape, I think either educationally in terms of embracing intellectual diversity and pluralism on our campuses. And we're not in better shape in terms of our civic health and our, our civic culture.

- Hmm. Thank you. And, and some of our, our upcoming questions give us sort of specific scenarios that perhaps get us away from those, our pension for creating abstract nouns that you're rightly criticized. Paul Jacob Mond, would either of you like to speak on this or, or shall I bring in the next question?

- I, I would say that critical thinking is a necessary component of a civic education, but I wouldn't say that it's the sole component of a civic education. And the reasons that you can teach critical thinking in many different areas you might teach critical thinking to in sciences, for example. But from my memory of being in citizenship in the 21st century, which Dan Stein and Deborah Satz and yourself and Josh Ober pioneered, you know, an important recognition is that students were going through Stanford and a lot of other universities acquiring engineering degrees and science degrees, STEM degrees, but not really thinking about these questions of citizenship. And the result was really well put by Fei FEI Lee, a professor of computer science at Stanford, who also led Google's artificial intelligence initiatives for a time. And she said that engineers would come to her and say that the technologies that they were developing at Google had massive implications for things like algorithmic bias and racial bias. They had massive implications for privacy, for the use of technology when it came to national security, but they did not have a language or set of ideas in order to discuss about those questions of citizenship, questions of complicity, as well as justice, the implications of their technology for democracy. So I think civic education is, is important because people with a STEM background, they also need to have this exposure to talking about ideas of epistemic democracy, ideas of separation, of powers and individual rights, understanding where conservatives and liberals both come from, which was one of the questions I was asked in the q and a and to, I support in my courses, the students get exposed to both conservative and liberal views. So in economic justice, for example, we learn about Milton Friedman, we learn about Robert Nozek and other conservative thinkers. We learn about Friedrich Hayek. So it would be a failure of my course. We only taught liberal egalitarian thinkers, but we, we learn about thinkers from all over the spectrum. And, you know, understanding where other people are coming from is going to be important in terms of working together as citizens in a pluralistic democracy.

- Hmm. Thank you Jacob, please.

- Yeah, I, I think that critical thinking easily slides into an, in a kind of individual intellectual virtue. And when people try to teach critical thinking, they're trying to teach the student who's going to then go out into the world that by themselves read new things, hear new things, how to engage with how to evaluate the thing that I do sympathize with in the impulse specific education. And I, there are things that I sympathize with, despite all my concerns and worries, I think doesn't easily map onto that. Mm. What we'd want out of a civics education is in part the skills in ongoing engagement and coexistence with someone with whom you do disagree, even though you think that their view is unreflective, even though in your judgment they have inadequately evaluated what it's like not just to reach a conclusion, which critical thinking can help you do you reach a provisional conclusion after weighing the evidence. But what it's like to go on disagreeing with another live person, with a neighbor, with a friend, with a fellow citizen. I, I think there's a skill there and the skill doesn't map onto a critical thinking skill.

- Hmm. Thank you. So this next question here, I think is pushing us to think about, about the, the boundaries of liberalism in the philosophical sense, as in, as they're related to the boundaries of pluralism that we were talking about before. So the question says, to what extent can or should critiques of liberalism at large be meaningfully integrated into civic education, rather than treated as peripheral or token perspectives? For example, the question says, could or should a professor who is an avowed communist or an avowed right-wing postliberal, perhaps a theocratic or some sort, should they be able, would to effectively teach a civics course within your conception of a civics education?

- First, to give the perspective from the US Air Force Academy, when I was there. So one of the professional military academies from the US government, there was a very strong commitment to a liberal arts education core

- Mm

- As necessary. The reality for American officer citizens, which is the American concept of civil military relations, is that they take oath to the constitution, not to a president or congress or, you know, some human chain of command at the moment. They take oath to the constitution, which means to a set of ideas and principles and to the rule of law. And so over time, the American professional military education community established and refined a commitment to a liberal arts corps for every cadet midshipman at the, at the Annapolis Naval Academy. So that meant, you know, philosophy and, and American politics to include American political thought and history and literature and a whole range for every cadet in every midshipman, which would include that whole range of I ideas just mentioned in, in in the question, non non-liberal, non-democratic, you know, non Republican, et cetera, encountered at some point in, in your education. And that certainly is what we did in the, the humanities and social science departments that I knew pretty well on, on the faculty, not just in the political science department. So that's the spirit we've tried to bring in, in the department here at Arizona State University. Again, blending liberal arts education, which encompasses this whole range of debates and questions, historical and, and philosophical with, with understanding this particular constitutional order in which, you know, one, one issue we haven't talked about here is that if you're a, if you're a student at an American university, public or private, large or small, you're already in a kind of elite status. There's an expectation that you might be a leader in civil society in, in the private sector and or in the public sector, in, in public affairs in some way. So some as the a CA statement of principle says to have some knowledge of duties as well as rights for those who were educating who are very likely to be leaders would be part of this complex package.

- I think. So I'll, I'll just note Paul, that, that you mentioned that in, in that context, everyone involved was swearing an oath to the constitution, which I think in some ways is the answer to, to the question that the audience member posed that the avowed Leninist or the avowed theocrat could have those views at home perhaps, but, but in their, their work capacity, they had to be dedicated to the constitution. So I is that it sounds like, and, and correct me if I'm wrong here, that that was a way of setting boundaries of pluralism sounds restrictive, but having a, a ground on which pluralism can exist.

- That's a pe it's a peculiar self-selected set of students who want to get into one Sure. The, the professional military academies or into ROTC, at, at, you know, mostly a public or large private universities. So that's a self-selected set of students. Different question at like Arizona State University where I am now. Yeah, no oath. Where it's a very broad funnel of students who want to, who wanna get in. Yeah.

- Fantastic. Got it. Well, Jacob, it looked like you wanted to get in. Is there an implicit oath to constitutionalism in the background

- Here? Oh, so I, I I think that the question is really on point and the question reaches some of the things that worry me because both prongs, both, both options seem unacceptable. On the one hand, if civics is to have any substantive equipment, as Paul's been saying, equipment to something like the American constitutional order, then that has, as you just said, boundaries and someone who is an avowed opponent of that kind of system, possibly even someone who is, say a parliamentary and constitutional monarchist, but certainly someone who is a Leninist or a theocrat could not in good faith teach as it were from within. And the, the original a UP statement on academic freedom from 1914 justifies a great deal of the academic freedom of the social sciences and humanities in, in the sense that the instructor owes their whole self, their whole good faith mind to the student and to the classroom. And that setting substantive boundaries in setting orthodoxies on what they can and cannot say and teach means that they cannot do their job in the right way. So the alternative is that we say there's a political litmus test to be able to teach civics in a way that there is not to be able to teach in the rest of the university. And then that directly violates academic freedom in a different way. It says that your civics curriculum doesn't play by the same rules as the university as a whole. This, this, this is exactly the kind of problem that keeps me up at night about the enterprise.

- Yeah. And, and again, in the past we solved this problem by just saying, well, everyone believes in

- Constant, everyone, everyone's a liberal democrat. But I mean that

- It's not true anymore.

- But partly that was about US politics in general being less polarized, but partly it was about who it was who was getting in the room of higher education in the first place. Yeah. There was a level of consensus that could be counted on in public after McCarthyism and after radical critics of liberal market democracy had been purged out of a, a lot, a lot of higher education. So sure everyone who's left could sign up, but that was an artifact of the exclusion already having happened.

- Hmm. Thank you. Min, please.

- Like Jacob, I think I would be opposed to a political litmus test for people to be able to teach civics. So I agree with Joseph Tasman, who used to be the chair of the philosophy department at Berkeley, and he was one of the faculty advisors for the Berkeley Free Speech Movement. And at the time, there was, during the time of McCarthyism, there was a pledge that actually all California employees, certainly all employees of the University of California had to sign owing that they were not communists. So I would be opposed to that because that would be contrary to freedom of speech. And in my courses, in addition to teaching conservatives like Friedman and Hayek and NOIC and others, we also read people who are non-liberal who are from the left. So we read Marks, for example, and if you think about it, it's important for students to be exposed to this, these views. I mean, at one point half of the human population was governed under a Marxist regime. Currently the, one of the richest countries in the world, the most populous country in the world is governed by a communist regime. So people should have some familiarity with these political beliefs and also be capable of critically examining them, understanding arguments on, on both sides.

- But, and you're, you're responding in part to Jacob, but there was the other horn of the dilemma, which, which was Jacob argued that the avowed theocrat or the avowed Leninist could not in good conscience teach civics of the kind that we've been talking about today. Do you think that's true?

- Well, I think if the avowed Communist thinks that promoting things like limited government, so defining liberalism as a philosophy of individual rights and limited government, If there's someone who's an advocate of completely unlimited government and despotism as well as the violation of individual rights, they probably would find it difficult to teach a, a course in, in civics. But it's hard to imagine a type of course that would, that could be taught by every single human being, right? Or a person of every single, single viewpoint. If you're teaching a a course on a biology, it's gonna be very hard to find people who are skeptics about biology to be able to, to teach it. So I think that we're trying to be as, have as big intent as possible. We're trying to get people to be able to understand and to live with people who disagree with them, as Jacob said earlier. But I think what you're probing, Brian, is whether there are certain limits to that toleration. Yeah.

- Well, that brings us back helpfully to the point where we started that pluralism and education is tremendously important, but it's also, I think something that, that we do need to rethink for the empirical facts of every era for our evolving understanding of the normative commitments to pluralism. And I want to, to thank, I want to thank our, our distinguished panelists, Paul Jacob Min, thank you so much for taking the time to be here today. It was just tremendously valuable to get your perspectives. I learned a ton from each of you and I'm deeply grateful for your participation here To the audience, thank you so much for joining us here. I apologize that we didn't get to all of the questions that were posed by our audience, but I hope that even if your question was not asked, that some of the issues you raised did come out in our conversation one. And thank you also to the Hoover team and the event staff for making this happen. Thank you all so much.

Panelists:

Paul Carrese is Director of the Center for American Civics, and professor in the School of Civic & Economic Thought and Leadership, at Arizona State University, serving as the School’s founding director 2016 to 2023. Formerly he was a professor at the U.S. Air Force Academy, co-founding its honors program blending liberal arts and leadership education. He teaches and publishes on the American founding, American constitutional and political thought, civic education, and American grand strategy. His forthcoming book is Teaching America: Reflective Patriotism in Schools, College, and Culture (Cambridge, May 2026). He has held fellowships at Oxford (Rhodes Scholar); Harvard; University of Delhi (Fulbright); and the James Madison Program, Princeton. He served on the advisory board of the Program on Public Discourse at UNC Chapel Hill; co-led a national study, Educating for American Democracy, on history and civics in K-12 schools with partners from Harvard, Tufts, and iCivics (2021); and served on the Civic Education Committee of the American Political Science Association (APSA). He is a fellow of the Civitas Institute, UT Austin, and serves on the Academic Council of the Jack Miller Center for America’s Founding Principles and History, and the executive and on the executive Council of the APSA. He is a Senior Fellow with the Jack Miller Center, and in 2025 was an Alliance for Civics in the Academy Visiting Scholar at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University.

Jacob T. Levy is the Tomlinson Professor of Political Theory and associated faculty in the Department of Philosophy at McGill University. He is the founder and coordinator of McGill's Research Group on Constitutional Studies, whose Charles Taylor Student Fellowship is devoted to an intensive non-credit yearlong reading group of major works in the history of political, moral, and social thought.

Minh Ly is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Vermont. His book, Answering to Us: Why Democracy Demands Accountability, will be published by Princeton University Press in March 2026. Anna Stilz, distinguished professor at Berkeley, writes, "this powerful book . . . is a must-read for anyone interested in the fate of democracy in our times." Professor Ly’s research and teaching focus on democratic theory, the rights and responsibilities of democratic citizenship, economic justice, global justice, and civic education. His work has been published in the Journal of Politics, the European Journal of Political Theory, the Review of International Political Economy, and other journals. Before joining UVM, he was a Lecturer at Stanford University and a postdoc at Princeton. Professor Ly earned his Ph.D with distinction in political science from Brown and his A.B. from Harvard.

Moderator:

Brian Coyne is an Advanced Lecturer in Political Science and serves as the Nehal and Jenny Fan Raj Lecturer in Undergraduate Teaching. He received his B.A. in Government from Harvard College in 2007 and his Ph.D. in Political Science from Stanford University in 2014. His dissertation, "Non-state Power and Non-state Legitimacy," investigates how powerful non-state actors like NGOs, corporations, and international institutions can be held democratically accountable to the people whose lives they influence. Coyne's other research interests include political representation, responses to climate change, and the politics of urban space and planning. In addition to Political Science, he also teaches in Stanford's Public Policy, Urban Studies, and COLLEGE programs.