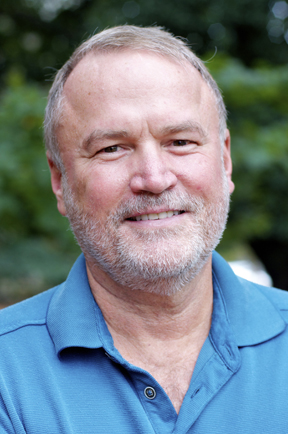

Bruce Caldwell, research professor of economics at Duke University and Hoover distinguished visiting fellow for the academic year 2019–20, is editor of Mont Pèlerin 1947: The Transcripts of the Founding Meeting of the Mont Pèlerin Society, a new volume from Hoover Institution Press.

The volume is published in commemoration of the seventy-fifth anniversary of the landmark event and marks the first time that its records—the originals of which are housed at Hoover’s archives—have been made widely available to scholars.

These transcripts include annotations made by the meeting’s chief organizer, the preeminent public intellectual Friedrich A. Hayek. The book also features an introduction by Caldwell, who provides explanatory notes throughout its chapters to help readers gain a deeper understanding of the historical context behind the conversations.

In this interview, Caldwell describes the life and work of Hayek and why he gathered a group of economists, philosophers, historians, journalists, and others in Mont Pèlerin, Switzerland, a small village on the shores of Lake Geneva, in 1947.

This meeting of the minds, Caldwell explains, was intended to revitalize classical liberal ideas that had been supplanted by the extremes of communism and fascism during the 1930s and overshadowed by the prospects for a socialist order that seemed attractive to a European continent wrecked by the Second World War.

The meeting included an array of public intellectuals and distinctive personalities, among them Hayek himself, philosopher Karl Popper, economist of the Austrian school Ludwig von Mises, and economists Frank Knight, Aaron Director, and Milton Friedman from the University of Chicago.

Caldwell asserts that while Hayek aimed to advance liberal ideas, he also encouraged disagreement and debate at the sessions, which covered a variety of subjects encompassing economic policy, society, religion, and the political future.

Finally, Caldwell maintains that a lasting legacy of the founding meeting at Mont Pèlerin is that the ideas exchanged there helped shape free-market-oriented policies, which would eventually expand individual freedom and prosperity to millions of people across the world in the latter half of the twentieth century.

How did you become involved in this project?

Bruce Caldwell: I was a visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution in the academic year 2019–20. At the time, I was working on a volume on the life and career of Friedrich A. Hayek, in which I wrote a chapter about the meeting that took place at Mont Pèlerin. It so happens that the Mont Pèlerin papers are housed in the Hoover archives.

Hayek’s secretary Dorothy Hahn took extensive notes of the meeting, and they are just fascinating. The caliber of people who attended the meeting and the discussions they had made for a great story. This year was an opportune date to release the volume because it coincides with the seventy-fifth anniversary of the founding meeting.

I also wanted to highlight the holdings of the Hoover Institution. I first visited Hoover back in 1991, when I began investigating Hayek’s ideas. The collection includes the works of not just Hayek but also other prominent classical liberal thinkers including Milton Friedman, Fritz Machlup, and Gottfried Haberler. It is truly amazing.

There is a final academic reason that I edited this volume. I wanted to challenge the canard that the Mont Pèlerin Society is a secretive cabal of academics and businessmen whose motive is to shape the economic policies of nations to, in the words of one critic, “make the world safe for corporations.” In the face of such criticisms, I thought it would be useful to show readers exactly what happened at the meeting.

Friedrich Hayek is talked about a lot among circles at the Hoover Institution. As a primer for our readers who don’t know: who is Hayek, what did he stand for, and why did he assemble this group of economists, philosophers, and historians at Mont Pèlerin in 1947?

Bruce Caldwell: Hayek was born in Vienna, Austria, in 1899. In the early 1930s, he came to the London School of Economics (LSE). At that time, he was mainly interested in monetary theory and the study of business cycles and while at LSE, he debated with John Maynard Keynes. This was before Keynes had written his General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, but nevertheless he was still considered to be a very prominent economist. The Keynes-Hayek debates is one reason why many people might know about Hayek.

Hayek had become an ardent critic of socialism, an ideology that was gaining momentum because it was considered by many as an antidote to the free-market system, which received the bulk of the blame for causing the Great Depression. Many in Europe also saw socialism as a middle way between the extremes of communism and fascism.

When World War II broke out, Hayek decided to pursue his criticism of socialism more widely. In 1944, Hayek became a household name in the English-speaking world when he published The Road to Serfdom. In 1950, he moved to the University of Chicago, where he wrote mostly about political philosophy. He shifted his focus away from economics and began to articulate the foundations of twentieth-century liberalism.

In 1962, Hayek returned to Europe and would go on to win the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1974. He was a prominent public intellectual, but not as popular with the public as someone like Milton Friedman.

Why did Hayek assemble these people at Mont Pèlerin in 1947? It was at the end of the war, and he decided that it would be a good opportunity to gather like-minded people who supported liberalism so that they could formulate and exchange ideas and think about the best ways to help rebuild their respective countries.

The meeting would not have been realized if it weren’t for a Swiss friend of Hayek’s named Albert Hunold. Hunold had raised money to start a journal, which was ultimately unsuccessful. However, since the funds were still available, Hunold told Hayek that they could be used in support of the meeting, which would ultimately take place at the Hôtel Du Parc, a beautiful venue in Mont Pèlerin, Switzerland.

Besides Hayek, who were some of the prominent intellectuals who attended the meeting?

It was a really a who’s who of classical liberals, consisting of other important members of the Austrian school of economics, such as Ludwig Von Mises and Fritz Machlup. University of Chicago economist Frank Knight was there, as well as three of his students from the 1930s: Milton Friedman, Aaron Director, and George Stigler. Other participants included Walter Eucken and Wilhem Röpke, two of the leading economists of the Ordoliberalism movement, Central Europe’s version of economic liberalism. The future Nobel laureate Maurice Allais was also in attendance.

The meeting included people from other disciplines. There were philosophers of science Karl Popper and Michael Polanyi. There were journalists including Henry Hazlitt of Newsweek and John Davenport of Forbes. There were prominent historians, including Veronica Wedgwood.

Finally, the meeting included some important members of foundations: Leonard Read, the director of the Foundation for Economic Education, and Floyd Arthur “Baldy” Harper, who would go on to found the Institute for Humane Studies.

It was quite a conglomeration of people. And there were a lot of strong personalities. It was great fun to read in the transcripts how they interacted with one another.

You write in the introduction that Hayek convened this group because “he was worried about the direction—political, social, intellectual, moral—of central Europe after the war and envisaged an organization that would put the few remaining liberals there in contact with peers in other countries as the rebuilding process began.” You just mentioned many of these liberal thinkers. Could you describe the state of liberalism before the Second World War?

Immediately before the Second World War, liberalism was in a horrible state. It was associated with the free-market system of economics that was blamed for causing the Great Depression. Many intellectuals in the west believed it was no longer a viable system.

At this time, communism had fully taken hold of Russia and surrounding states, and there was fascism of various varieties in Italy, Spain, and Germany. None of these systems were palatable in post-war Europe, which is why I said earlier that socialism became seen as a viable option for the future of the continent. And it certainly was embraced by the European intelligentsia.

There was a predecessor to the Mont Pèlerin meeting that took place in Paris 1938. It was called the Colloque Walter Lippmann. Walter Lippmann was a very prominent newspaperman in the early part of the twentieth century. He was basically the equivalent of Walter Cronkite for people who read newspapers. Lippmann had been a progressive in the early part of his career, but while writing for the Herald Tribune in the 1930s, he soured on the New Deal. He wrote a series of essays for The Atlantic about the revitalization of liberalism that was eventually published in a book called The Good Society.

Hayek was instrumental in setting up the colloque, or symposium, named in Lippmann’s honor. The meeting included many liberals from Europe, and Lippmann himself also came. It included five sessions, all of which focused on the issue of whether liberalism was doomed or if it could be revitalized, and if so, how, given the dire situation in Europe, which was on the brink of the Second World War.

These intellectuals wanted to create a permanent center in Paris. Those plans were foiled by the outbreak of war.

What sorts of ideas were prevailing in Europe at the time of the meeting?

The meeting takes place in April 1947. In summer of that year, the Marshall Plan was first announced. All four of the Allied powers (United States, United Kingdom, France, and the Soviet Union) had moved into Germany, Austria, and other countries that had been under the purview of the Axis powers. These countries were ravaged by the war. There was rationing of food and other resources, currencies were depressed, and price controls were widely in place. There was the prospect of massive starvation, particular in Germany. The British exchequer complained that the Allies were paying reparations to the Germans in order to keep the people from starving to death. This German crisis was one of the initial subjects discussed at the first Mont Pèlerin Society meeting.

In the United Kingdom, the Labour Party had been arguing that the war effort was about not only defeating fascism but also for creating a new world of socialist planning. Labour maintained that certainly England, and perhaps all of Europe, should not return to the old days of laissez-faire economics.

What is classical liberalism?

That's not a simple question. Classical liberalism is associated with the concepts that people are equal in dignity and under the law. Originally, it had its origins in the seventeenth century, in the writings of figures like John Locke, people who rejected both ecclesiastical and political absolutism.

As outlined in his 1960 book The Constitution of Liberty, Hayek favored a free-market system in a democratic polity, operating under the rule of law, with strong and well-defined protections of individual rights, including such things as freedom of religion, freedom of speech, freedom of press, and the ability to own and exchange private property.

In terms of political setup, classical liberalism is associated with various institutions that would constrain simple majorities from irresponsibly wielding their authority and would protect the rights of minorities. In the West, this has usually taken the shape of a bicameral legislature and separation of powers between the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of governments, and a strong emphasis on equality before the law.

The concept of reducing the power of groups and individuals to abuse others also prevails in the classical liberal’s view of an ideal economic system. To the classical liberal, a free system is one that is competitive, so that no entity is able to monopolize the means of production.

Classical liberalism should be distinguished from more progressive variants of liberalism, which grew out of liberalism in America and England in the early 1900s. These called for much further intervention in economic and political realms than classical liberals endorsed.

Was there an agreement at Mont Pèlerin about principles, particularly on what it means to be classically liberal?

Bruce Caldwell: No, not at all. This is one of the most intriguing aspects of the transcripts. You will see a lot of disagreement about various issues. In his introductory remarks, Hayek said that disagreement during the proceedings was to be encouraged. I'll give you an example: the first couple of sessions carried the title “’Free Enterprise and Competitive Order.” So free enterprise would be kind of a very laissez-faire approach. It would be associated with the philosophy of Ludwig von Mises, and it meant relatively little or no role for the state beyond the protection of life and property, prosecution of fraud, and national defense. People who were affiliated with the Foundation for Economic Education were in line with these beliefs as well.

However, most of the other people at the meeting saw other reasons for state intervention to promote a competitive order. And within this group, there was a lot of debate on what could justify state intervention, as well as what forms it should take. One example is whether central bankers should be guided by rules when conducting monetary policy or whether their decision making should be discretionary. Another is whether policies should apply equally to everyone or whether certain groups should get special benefits—farmers, for example, were seen by some as warranting protection, while others disagreed.

These sorts of debates took place, and sometimes they were quite fiery. Milton Friedman often told a story about how, at the end of one session, Ludwig von Mises stormed out and said, "You're all a bunch of socialists."

How was the agenda organized for the April 1947 founding meeting of the Mont Pèlerin Society?

Bruce Caldwell: Hayek was eager to have discussions among people who were like-minded but who would disagree on the details. His own agenda was to see if there were principles that could be identified that would strengthen arguments for specific policies that might be applied to labor markets, to agriculture, to monetary theory and monetary policy, and others.

Hayek placed five sessions on the agenda, and the rest of them were organized by the other scholars in attendance. His own sessions included the ones on free enterprise and the competitive order and the ones on the problems of Germany. The group very much wanted to figure out whether there were policy responses that could be undertaken to help improve the horrible situation in that country.

One session that Hayek organized that was especially noteworthy was on the role of history in public education. Today, there is considerable debate about how history is taught in schools and how its study should interpret the triumphs and tragedies of our nation’s past. These types of debates were also taking place back then. One constant source of contention was about whether capitalism was the cause of the Great Depression. Those who believe it was indeed the cause often advocated some form of socialism in the postwar period. Thus, Hayek wanted to examine historians’ roles in teaching about the economic development of various countries.

Hayek set up another session on the prospects for a European federation, which again is an extremely timely topic. A European federation was something discussed by Hayek and British economist Lionel Robbins both before and after World War II. As opposed to the modern European Union, Hayek and Robbins envisioned an entity that was less political in nature and more directed at eliminating barriers to trade between nation-states.

Hayek’s last session just happened to land on Good Friday. The topic was appropriately called “Liberalism and Christianity.” There was a common belief that Christian social teaching and liberalism, particularly in Europe, were in opposition to each other. In Hayek’s mind, this was just an accident of history. This antagonism didn’t need to exist. Interestingly, the session was chaired by the American economist Frank Knight, who was famously hostile to Christianity.

The very last session (not organized by Hayek) was called “The Present Political Crisis.” This was basically about how to deal with the rise of the Soviet Union and its ambitions in Europe. This obviously will have resonance today, given Russia’s recent aggression in Ukraine.

Will you describe the legacy of the ideas discussed at the Mont Pèlerin Society in America, Europe, and beyond?

Bruce Caldwell: The ideas discussed at the founding meeting of the Mont Pèlerin Society had a significant impact in shaping policy making in the West and continue to resonate to this day.

At the meeting, Milton Friedman defended the idea of a negative income tax as an antipoverty measure. Essentially, this means that the state would give money to people who earned below a certain income threshold. This idea reappeared in policies like the earned income tax credit in the United States in the mid-1970s.

At the meeting, participants, especially the German Ordoliberals Eucken and Röpke, advocated curing the wrecked German economy by adopting currency reforms and removing price controls. In 1948, both reforms were instituted, and this led to what has been later called the “German Miracle.” Within a decade, West Germany rose from ruins to being the most important economy in Europe.

Generally, the distinguished group who participated in the first meeting were articulating the principles of free-market economics. Over the years they argued for the benefits of allowing the free exchange of goods, services, and capital across borders, and removing barriers to trade. They helped advance ideas that were later embraced by the United States and other nations in the 1980s and 1990s and that led to vast increases in wealth and individual freedom. Unfortunately, free trade is under fire today, and many young people in the United States seem to think that socialism is preferable to a system of free markets. Reading the words of Hayek and his peers will introduce them to a very different perspective.