By Jonathan Movroydis

Hoover Institution (Stanford, CA) – Colombia’s emergence from decades of violence and political turmoil can be attributed to its strong diplomatic relationship with the United States, in combination with the creative and audacious solutions inspired by leaders in Bogotá, argued Juan Manuel Santos, the country’s former president (2010–18), in the latest episode of the Hoover Institution’s Battlegrounds series, hosted by Fouad and Michelle Ajami Senior Fellow H. R. McMaster.

Santos explained that the strong relationship between Colombia and the United States originated in the early 1960s. Just three months into his presidency, John F. Kennedy established the Alliance for Progress, a multi-billion-dollar economic cooperation and development program aimed at preventing the rise of Marxist revolutions, as had transpired in Cuba at the end of the previous decade, as well as promoting democracy and implementing meaningful land reforms in Latin America. Kennedy became the second American president (after Franklin Delano Roosevelt) to visit Colombia, during his four-country tour of South America and the Caribbean in December 1961.

While such efforts helped support the Colombian government against a communist takeover, the country was to become mired in four decades of violence, not only against Marxist guerillas but also against drug cartels, who profited handsomely from the international distribution of cocaine, processed from the Andean region’s indigenous coca plant. Santos noted that by the end of the twentieth century, these violent and heavily armed groups together controlled two thirds of the country, leaving the government in an increasing unstable and vulnerable position.

The country’s prospects turned around in the early 2000s, after Bogotá launched Plan Colombia, an integrated strategy aimed at building up the military, strengthening democratic institutions and the rule of law, reviving the economy, and expanding counternarcotics operations. Since 2000, US Congress has appropriated more than $10 billion in support for Plan Colombia and related programs.

Santos explained that Bogotá has historically maintained strong ties with Washington because it has been able to cultivate relationships with individual American leaders of both major political parties, as well as leaders in branches of the US armed forces, whom they have relied upon for military equipment and training.

Santos asserted that Bogotá’s reforms over the past two decades have proved to be enormously successful. He boasted that the Colombia National Army, who fight in the treacherous terrains of the Andean mountains and the Amazonian jungles, include among its ranks the most elite anti-guerilla warriors in the world. The Colombian National Army’s “Lancero” training school, originally established by US Army Ranger commander Ralph Puckett in the mid-1950s, has produced perennial champions of the annual Fuerzas Commando competition, sponsored by United States Southern Command.

“The students became better than the professors,” Santos teased. “[In last year’s competition] I am proud to say that Colombia was number one and the US was number two.”

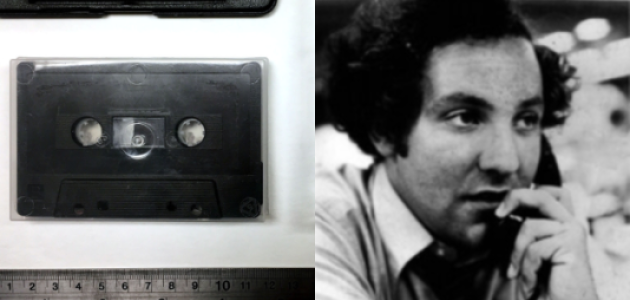

Santos described the Colombian National Army’s improbable 2008 rescue of fifteen people taken hostage by FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) rebels in the southern-central region of Guaviare. Among the hostages were three American military contractors and Íngrid Betancourt, a Colombian politician who also held French citizenship.

Colombia received significant pressure from Washington and Paris for the release of the hostages, prompting then defense minister Santos and intelligence officials to design an audacious plan: supplant the communications of the captors and deceive them into believing that they were receiving orders from FARC leadership to transition the hostages to a humanitarian mission via helicopter. The plan was a success.

“That helicopter and humanitarian mission was the Colombian army intelligence,” said Santos. “Without spilling one drop of blood, we rescued fifteen people from the fiercest and strongest of guerilla forces.”

Santos also maintained that while the Colombian government has made inroads toward greater political stability, these gains still need to be consolidated. Despite eradication of hundreds of thousands of acres of coca plants and the extradition of more than a thousand cartel members to the United States, the fifty-year international war on drugs still rages on. Also, peace with the FARC hasn’t been fully achieved, despite a historic treaty brought forth by the Santos-led government in 2016, for which Santos was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

On both of these fronts, Santos argued, leaders in Colombia need to develop more dynamic strategies than just taking the fight to criminal organizations. As president, Santos in collaboration with Washington, advanced a plan to help small farmers substitute other crops for coca. He has also argued that the peace agreement with the FARC enabled the government to regain a stronger presence over land that continues to produce coca.

Santos also addressed the challenge of economic disparities in Latin America, which is considered to be the most unequal region in the world. Thirty percent of Latin Americans live below the poverty line, while only 3 percent of people are considered to be high-income earners. He is concerned that worsening economic conditions will lead to more social unrest, noting that even Chile, which has touted high rates of economic growth over the past three decades, experienced violent demonstrations just prior to the pandemic because of its citizens’ anger over pervasive income differences. The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated these divides, disproportionately impacting lower-income earners whose jobs cannot be performed remotely.

Among the poorest and politically unstable countries in the region is oil-rich Venezuela under the rule of President Nicolás Maduro, which Santos compared to a plane running out of gas.

“It can either crash or have a soft landing,” Santos recalled saying to President Trump during a 2017 meeting in New York.

By a “soft landing,” Santos meant a peaceful political transition of power in Caracas supported by neighboring countries and larger regional stakeholders, including the United States, China, and Russia. Santos warned against further US sanctions against Venezuela, arguing that such policies further deteriorate the economic conditions of the people and embolden corrupt leadership, which will hasten the country’s ruin.

“We have to be audacious and creative in the solution,” Santos said. “I truly believe a negotiated solution is possible, because Maduro knows that his days are not eternal.”