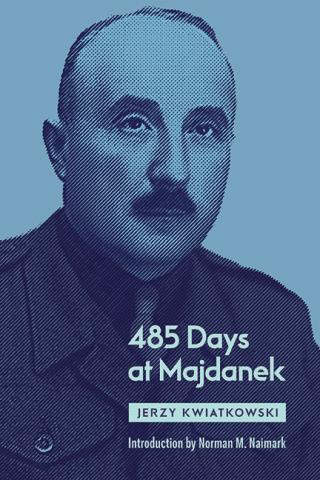

In this conversation, Senior Fellow Norman Naimark talks about 485 Days at Majdanek (Hoover Institution Press, 2021) a memoir by Jerzy Kwiatkowski, a lawyer, banker, and industrialist who was incarcerated as a political prisoner at the Majdanek concentration camp in Nazi-occupied Poland during the Second World War.

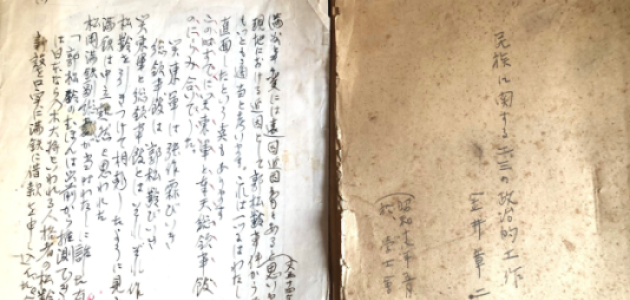

Naimark wrote the introduction for the first unabridged English edition of the memoir, translated from the original manuscript housed in the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. In this interview, Naimark describes the motives behind the Nazi attack on Poland during the Second World War, the Nazi prison camp system, and why Majdanek was built in the eastern city of Lublin, close to Poland’s border with Ukraine.

Naimark provides historical insights on Kwiatkowski’s life and career as a member of the Polish intelligentsia and the author’s detailed account of the atrocities committed at the Majdanek camp. Furthermore, Naimark also reflects on what important lessons Kwiatkowski’s memoir offers about how to cope with human rights abuses.

What was the objective of the German attack on Poland during World War II?

The occupation of Poland came in two stages. The first stage started on September 1, 1939, when the Nazis attacked Poland. The idea was to redraw the European map and eliminate Poland as a country in the center of the continent. The Germans had signed a nonaggression pact with the Soviet Union prior to the attack, and the two totalitarian powers essentially decided to divide Poland in half.

The Nazis saw the Poles as “Untermenschen” or subhumans, and wanted to subordinate them. The Nazis also wanted the Poles to be a primitive workforce for the Nazi empire. The intelligentsia, the educated class consisting of lawyers, doctors, engineers, and politicians, was to be eliminated. Tens of thousands ultimately were killed.

The second stage came on June 22, 1941, when the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union and along the way occupied the entirety of Poland. The Nazis’ objective was to extend their empire eastward and subjugate the Poles.

Why were Majdanek and similar concentration camps constructed by the Nazis?

The Majdanek camp had been planned in summer 1941. It was located on the outskirts of the city of Lublin, close to Poland’s eastern border with Ukraine. The Nazis’ strategy was to make Lublin the center for the SS secret police as they occupied Russia. The SS established factories and settlements throughout the city. Majdanek would thus serve as a labor base for those enterprises.

Majdanek was built in fall 1941, just before the Nazi advance towards Moscow slowed in December. When the Nazis’ fortunes began to be reversed, beginning in 1942, Majdanek’s functions began to change. In addition to being a concentration camp, it became an extermination camp. Jews were detained there, and gas chambers and crematoria were constructed. It also remained a labor camp for Poles.

Will you describe the conditions of Majdanek?

The camp was built anew, unlike many other camps, which were repurposed from military barracks or factories. The building materials were inferior, the housing arrangements were horrendous, and the water supply for its first two years was very uneven. Eventually, Majdanek was linked to Lublin’s water supply, but during that period the conditions of the camp were extremely unsanitary. The prisoners were lice ridden, and there was no water with which they could wash. There was rampant disease, especially typhus, from which many thousands of prisoners expired.

There was also the issue of hunger. Unlike earlier in the war, the Nazis were not as reliant on the prisoners for slave labor and didn’t care if they died from starvation. The food rations were thus sparse. In addition to dying of hunger, prisoners were executed in gas chambers, by firing squad, or just by being beaten to death.

Who was Jerzy Kwiatkowski, and how did he end up at Majdanek?

Jerzy Kwiatkowski is a very interesting and intelligent character in this story. He was well educated and a veteran of World War I. At the time of the Second World War, he was a factory director. He helped supply arms and money to the Polish resistance. Consequently, he was arrested by the Gestapo and sent to the Majdanek prison in 1943 with other members of the resistance.

What is unique about Kwiatkowski’s account of the war and incarceration at a Nazi prison camp?

Kwiatkowski had a phenomenal ability to recall the events he experienced at Majdanek. The memoir was written almost immediately after his liberation in May 1945. He memorizes dates. He recalls precise names of people, including SS officers and prisoners, even those inmates who would eventually die. He sketches a diagram of the camp. Ultimately, the reader can come to terms with Majdanek’s complex workings through Kwiatkowski’s incredibly rich narrative.

Kwiatkowski was also a quite interesting man. He was an archetypal member of the Polish intelligentsia during the interwar period. He was highly cultivated. He was also fluent in German, and that helped in numerous ways, because the SS would often assign him to administrative tasks rather than hard labor. His multilingual abilities also provided him the advantage of understanding events unfolding at the camp. He shares with the reader very insightful observations about mankind, in particular about the behavior of the Nazis, that are very useful for scholars and the public interested in that period. In other words, he is not just a prolific documenter of facts, but he is also a remarkable commentator about those facts. He represents a generation of Poles who fought in World War I and subsequently rebuilt the Polish state in the interwar period, only to see it tragically taken over by the Nazis and then the Soviet Union during the Second World War.

What is new about this uncensored English edition?

There are significant amounts of new information in this edition. In the first publication, in 1966, Polish censors had excised content that was critical of Communists and praiseworthy of anti-Communists. The censors especially didn’t like Kwiatkowski’s criticisms of Soviet POWs, Russians, and Ukrainians.

The new edition also includes Kwiatkowski’s attitude toward Jews, which is somewhat ambivalent. As I wrote in my introduction to the book, the author is not totally free of the prejudices of his generation, and in some ways, he harbors some anti-Semitic sentiments.

Kwiatkowski is a quite conservative Roman Catholic. His religion is a very important part of his personality and is integral to his ability to survive the camp. He provides a detailed description of a Catholic medal he wears. In the censored edition, he just wears a medal.

These are small but very important details. When this type of information is censored, it undermines our ability to understand better the memoir and its usefulness in historical scholarship. The Hoover Archive has the original manuscript, which was published in its original form, in Polish, in 2018. This new English edition is particularly important because it includes information from letters and other materials in the Kwiatkowski papers at Hoover, such as conversations he has with publishers in Poland and how he himself deals with issues surrounding the book’s publication. It thus paints a fuller portrait of Kwiatkowski, the man. We also receive more information on how Kwiatkowski thinks about himself, and that deepens the reader’s understanding of this important era in human history.

Kwiatkowski and others have testified that the most consistent type of violence at the camp came from prisoners who were delegated authority to oversee other inmates. Will you describe the security situation in camps like Majdanek, especially the brutal behavior exhibited by some prisoners?

The Nazis set up these camps in a very specific manner. Camp directors were trained to follow the model established in Buchenwald when it was established in 1937. The objective was to devote the least amount of German military personnel to the camps as possible, so that they could be deployed to battlefields. Hence, the camp commanders came to rely increasingly on prisoners to keep order and discipline. Many times, the Nazis chose criminals to assume positions of authority. These people were chosen for a reason: they were morally corrupt, tended to be violent, and were willing to use force at the least hesitation. They also stole from other prisoners. In fact, in the camps there was a pervasive hierarchy of violence and thievery.

This was all very purposeful on the part of the Nazis. It was a vicious system, where everyone picked on the person below them in the hierarchy and conspired for the smallest ration of food just to stay alive. There were also beatings and hangings, most of which were carried out by prisoners. Sometimes the abuse was inspired by nationalistic rivalries within the camp. Sometimes it happened within national groups. Typically, however, there was solidarity among people of the same ethnic background.

Was this strategy deployed by the Nazi SS, in part, to keep the prisoners divided?

Yes, partly, it is a divide and rule strategy. When I first read the memoir, I was struck by a number of different realities. It seemed crazy to me that there were lice-ridden prisoners sleeping together in really close quarters. Then, in the morning, the guards insisted that the prisoners make their beds in a certain way, despite the fact that there were no blankets, just rags. There was a surface regime of order and discipline, but beneath it there was filth, hunger, and violence.

The Nazis would also make all the prisoners line up and watch a particular prisoner be beaten for violating the camp’s rules. Ultimately, prisoners were beating prisoners, and prisoners were watching prisoners beating prisoners. There was an SS guard or two who might supervise the routinized prisoner violence, but generally this was carried out without much direction from the top.

How do you think this work may inform the current society on how to cope with human rights abuses?

I think there are a lot of lessons to be learned. Alexei Navalny, the political opponent of Vladimir Putin, has just been imprisoned in Russia. In August 2020, Navalny was poisoned with a nerve agent, and after coming back to his country from being healed in Germany earlier this year, he was sentenced to three and a half years of incarceration, which he is now serving in the notorious Penal Colony 2 in Pokrov, one hundred kilometers from Moscow. I feel awful for Navalny, because he’s been put into a situation where he could be possibly attacked or tortured. His health is deteriorating, and he has been on a hunger strike. We also hear about human rights abuses and forced labor against the Uighur Muslims at re-education camps in China’s Xinjiang Province. The life in these camps is inevitably brutal and mean.

These cases demonstrate that history doesn’t repeat itself exactly, but it has a frightening way of teaching us who we are and what we are capable of as human beings.

What do you believe is Kwiatkowski’s biggest contribution to historical scholarship?

Much has been written about Nazi war crimes, specifically the incarceration of Jews in concentration camps and the Holocaust. Kwiatkowski’s memoir contributes to this history, because he helps document one of the worst massacres of Jews during the Second World War. At a certain point in the war, SS chief Heinrich Himmler decides to kill all the Jews living in the Lublin area. The SS captured approximately 18,000 Jews, detained them at Majdanek, and ordered them to be killed by firing squad. All of this took place in twenty-four hours, according to Kwiatkowski.

In this memoir we also learn about the Nazi persecution of the Poles, which is too little understood and talked about. When the Poles resisted the Germans, they were taken as hostages to Majdanek, and many of them were killed. Jews obviously died by the millions in Nazi camps, but the Poles also suffered and died in untoward numbers.

Finally, we hear a lot about Auschwitz in memoirs concerning the Second World War, but rarely do we learn about other concentration camps. Thus, Kwiatkowski’s account is an important addition to scholarship about Nazi war crimes and the concentration camp system.