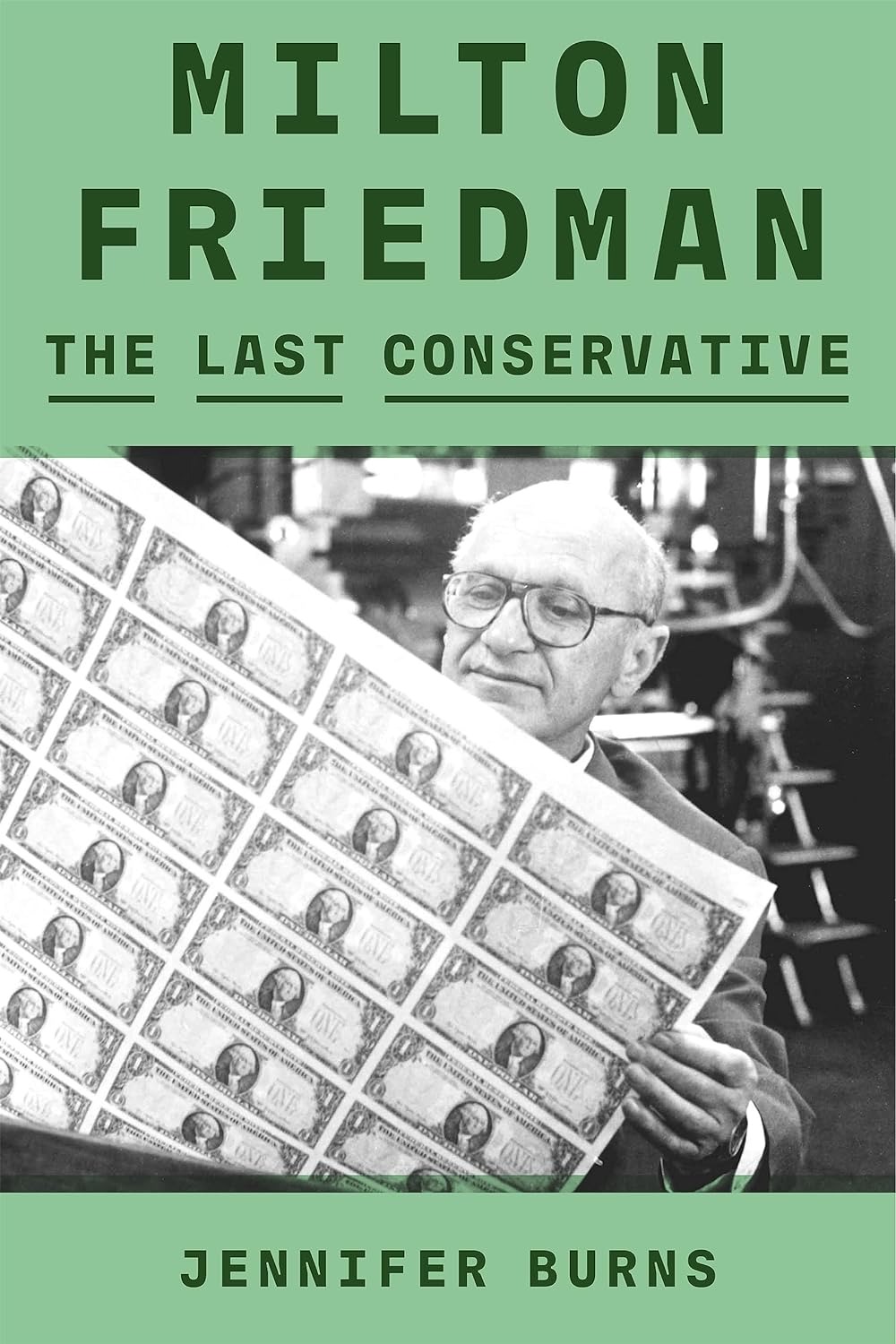

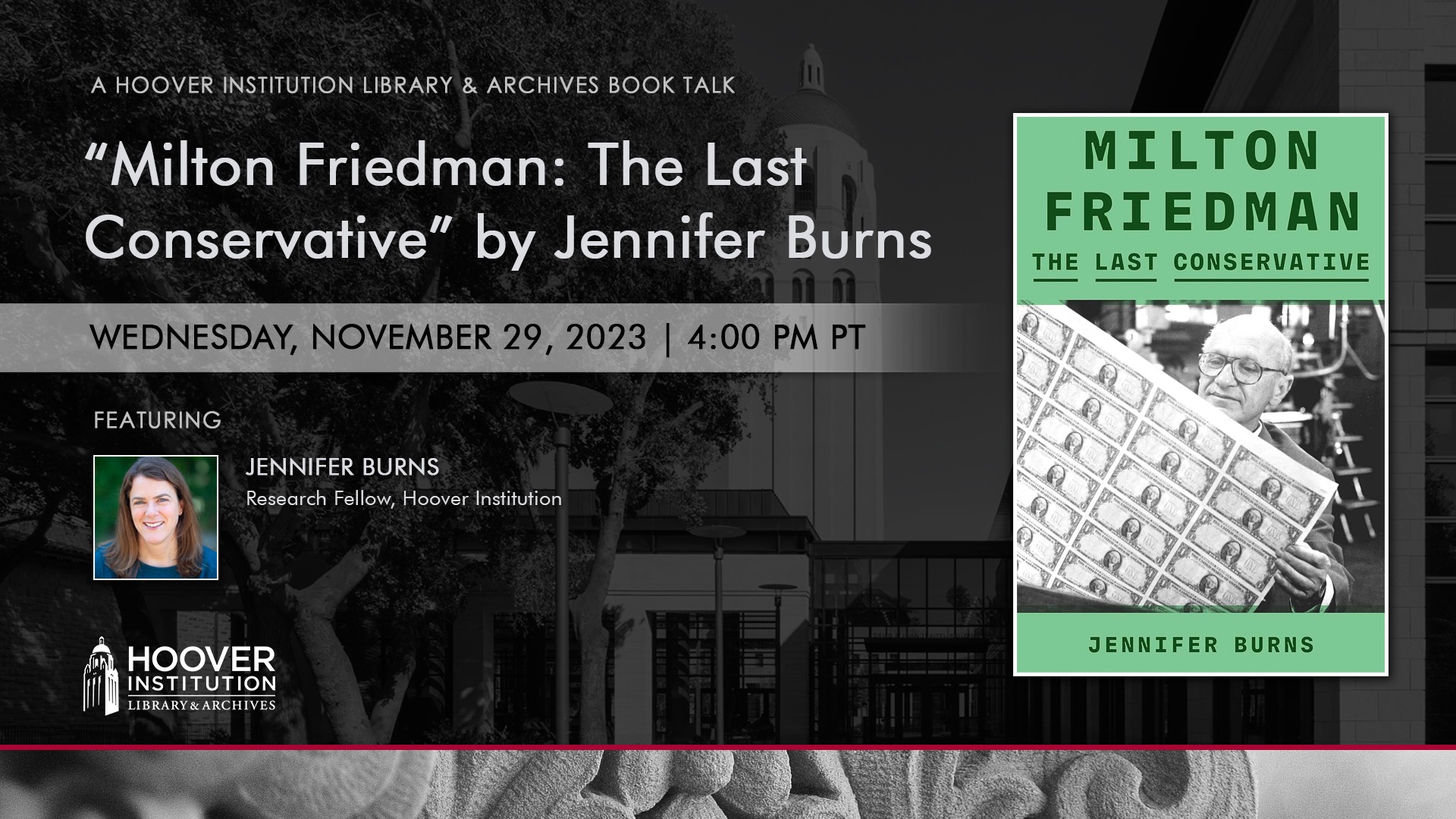

On Wednesday, November 29, the Hoover Institution Library & Archives hosted Stanford associate professor of history and Hoover research fellow Jennifer Burns to discuss her new book, Milton Friedman: The Last Conservative (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2023). Once a Hoover senior research fellow, Friedman has been revered as one of the most influential economists and public intellectuals of the twentieth century.

The aim of the book project, according to Burns, was “to show how [Friedman] was shaped by his times and how he shaped his times,” most notably through his public-facing work as an iconoclastic economist and popular speaker, author, and teacher.

Deputy director of the Hoover Institution and Everett and Jane Hauck Director of Library & Archives Eric Wakin opened the event by thanking the Hoover Board of Overseers, Hoover donors, and Hoover Library & Archives staff for making possible the scholarly work of the Institution—and books such as Burns’s, which drew heavily on primary sources held within Hoover’s collections. Wakin also introduced Professor Burns and shared some of the glowing early reviews of her book, the first comprehensive intellectual biography of Milton Friedman.

In her talk, Burns traced Friedman’s career from his humble origins as the son of Jewish immigrants in small-town New Jersey, through his impactful time at graduate school at the University of Chicago during the depths of the Great Depression, through his service in the federal government as a staff statistician, to ultimately his attaining the status of world-renowned public intellectual.

Professor Burns emphasized how heavily she drew on sources housed within the Friedman collection at Hoover’s Library & Archives to write the book. She said that the project “could not have happened without the Hoover Library & Archives,” which she also spoke of as “a place like no other” and one of the finest archival institutions in the world.

Milton Friedman was many things, according to Burns: economist, author, Hoover fellow, leader of the monetarist school, television host, onetime Boy Scout, and, intriguingly, a “policy innovator.” Among the policies he helped to champion into adoption were state educational vouchers, income tax withholding, the earned income tax credit, and the floating exchange system in international currency markets.

But Burns also stressed that Friedman did not think or act alone during his career. He had a network of close friends and colleagues that included several pioneering women economists, such as Anna Jacobson Schwartz, Margaret Reid, Dorothy Brady, and his wife, Rose. Ongoing conversations with these women in Chicago, at summer gatherings in New England, and via correspondence helped Friedman further develop and refine many of what would become his most popular ideas before they entered the public sphere.

Burns noted that Schwartz had a particularly key influence on Friedman. Trained in economic statistics and steeped in British monetary history, Schwartz brought invaluable amounts of time, energy, experience, and effort to her joint publication with Friedman, A Monetary History of the United States. Schwartz hand-compiled and manually analyzed reams of data on bank vault cash balances and other measures of the money supply, sometimes physically traveling to banks to acquire data that economists today could obtain with a few keystrokes.

Prejudice against women economists prevalent in the 1950s and 1960s was a barrier to Schwartz’s pursuit of a doctoral degree from Columbia University. However, following the publication of A Monetary History—and a strongly worded letter of intervention from Friedman to the chair of Columbia’s economics department—Schwartz was given due consideration and ultimately achieved her PhD.

In her talk, Professor Burns relayed this story and other anecdotes to illustrate that the discipline of economic history features no fewer episodes of emotion and passion than do other areas of history, possibly a surprise to those tempted to write off this field as “boring” or “dry.”

Following Professor Burns’s presentation, attendees had the opportunity to engage in a question-and-answer session with the historian. Audience questions prompted Burns to speak on Friedman’s initially contentious, then warm and friendly relationship with William F. Buckley Jr.; his views on Hong Kong and the prospects of eventual democratization in China (he was bullish on the prospect); what Friedman might say about the state of the economy today; and how Burns herself related as a biographer to her subject.

While Burns was candid about the fact that Friedman did have a certain desire “to be the smartest guy in the room,” she also praised his willingness to present views against the grain of disciplinal orthodoxy within the field of economics. Burns suggested that this appetite for dissent is in some ways lacking in the academy today and is instructive for current and future scholars.

Burns’s final comment highlighted one of Friedman’s other virtues: intellectual honesty. When he was wrong in his analysis of a particular issue, he was not afraid to admit it. In fact, he was willing “to go on the record in the newspaper and say, ‘I was wrong.’” This too, Burns suggested, remains an instructive and relevant lesson for anyone engaged in any intellectual or academic enterprise today.

Burns’s talk and the subsequent discussion were followed immediately by a reception and book signing in the Stauffer lobby. Interested readers can learn more about Milton Friedman: The Last Conservative on this page.

WATCH THE RECORDING